Djamaluddin Adinegoro

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

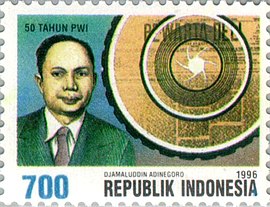

Djamaluddin Adinegoro (14 August 1904 – 8 January 1967) was an Indonesian press pioneer. He is known as a reporter, writer, and political analyst. Through his writing in various newspapers, Adinegoro has made a great contribution in developing journalism[1] and the Indonesian language. His name was immortalized as a journalism award in Indonesia: the Adinegoro Award.[2][3][4] Djamaluddin was a younger half-brother of Muhammad Yamin.

"Adinegoro" is a "nom de plume". He was born Achmad Djamaluddin. Later in life he was awarded the title Datuk Maradjo Sutan by his matrilineal clan in Minangkabau.[5]

Early life

[edit]Djamaluddin was born on 14 August 1904, in Talawi, Sawahlunto, West Sumatra.[6] His father Tuanku Oesman Gelar Bagindo Khatib was a "penghulu andiko" or "regent" of Indrapura. Coming from a ruling family, Djamaluddin had the privilege to be educated in Dutch schools. After graduating from the Europeesche Lagere School (ELS), Djamaluddin and his brother Muhammad Yamin continued their study in Hollands Indische School (HIS) in Palembang.

Then he moved to Batavia to study in the medical school: School tot Opleiding van Inlandsche Artsen (STOVIA). After studying he spent his spare time to read and write many articles for the Tjahaja Hindia magazine. As suggested by Landjumin Datuk Tumenggung, who runs the magazine, Djamaluddin used Adinegoro as his pseudonym in his writings. Because of his great interest in becoming a reporter, Adinegoro left STOVIA and traveled to Europe to study journalism.

Career

[edit]During his stay in Utrecht, The Netherlands, Adinegoro had the opportunity to work as a voluntary assistant for several newspapers. After that he moved to Berlin, Munich, and Warzburg to study journalism, geography, cartography, and philosophy. From Germany, Adinegoro visited the Balkan countries, Southeast Europe, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Egypt, Abyssinia and India that gave him ideas to write.

Adinegoro's travel journal first appeared in Pandji Pustaka magazine and was published as a book, A Journey to the West. At that time his inspired writing has gained attention from the youths in the Dutch East Indies. His writing was readable, filled with knowledge, popular and easy to understand by readers who didn't have high education.

In mid-1931, Adinegoro returned to Indonesia. He worked in Balai Pustaka Jakarta and received an assignment to lead Pandji Pustaka magazine as well as a writer in Bintang Timoer. Not long afterwards Adinegoro accepted an offer to lead a newspaper Pewarta Deli in Medan.[7]

Under Adinegoro's leadership, Pewarta Deli had many improvement and changes, not only in terms of layout and news reporting, but also in the choice of articles. The attention of all Pewarta Deli's readers was aimed at the brilliance of Adinegoro's writings. Uniquely, his articles about the war in Abyssinia and the civil war in Spain were attached on a map that showed the location of the war, making it easier for readers to understand the reports. During that time attaching pictures or maps in a local media was uncommon.

On 25 August 1932, Adinegoro married Alidar binti Djamal, a woman from Sulit Air, Solok, West Sumatra, his friend from STOVIA, with whom he had five children. Although living a life of scarcity, Adinegoro had a high commitment as a reporter and writer who produced two literary works: Darah Muda and Asmara Jaya.

In Pewarta Deli editorial, Adinegoro expressed his thoughts about colonialism, the struggle for independence, nationalism and education. His writing was always sharp and elegant. Because of his brilliance in choosing words, Adinegoro always managed to escape the legal traps made by the Dutch colonial government in Persbreidel-Ordonantie. The colonial government was always suspicious due to his activities in the nationalist movements.

During the Japanese occupation, Adinegoro led the Sumatera Shimbun daily. In May 1945, After being assigned as head of the secretariat of the Sumatra Central Advisory Council, Adinegoro moved to Bukittinggi.[8] After the proclamation of independence, Adinegoro was assigned as head of Sumatera National Committee. He encouraged the people of Sumatera to carry out the President's command: to take over the government from the Japanese and declare Proclamation of Independence along with the local leaders. Besides running the Kedaoelatan Rakjat newspaper, Adinegoro also established Sumatra branch of Antara newswire service.

In 1947 Adinegoro's health was declining, and he moved to Jakarta. After regaining his health, he started to write again for Waspada daily in Medan. Adinegoro's spirit was raised again when he and his press colleagues set up a weekly, Mimbar Indonesia. In this well-known magazine he wrote about foreign affairs politics, which became his expertise.

Due to his wide-ranging knowledge, Adinegoro's writings always attracted people's attention. For example, his writing and report on the Roundtable Conference was very amazing, smart, and informative. He was able to see problems clearly and provided criticisms and arguments in a very smooth manner. In a short time Mimbar Indonesia became recognized among the Indonesia press.

Since October 1951, Adinegoro led the Indonesian Press Bureau Foundation (Yayasan Pers Biro Indonesia Aneta/PIA) which liquidated the colonial press bureau. PIA has published Indonesian, Dutch, English bulletins, as well as bulletins for finance and economy, and also news in English. Once after the PIA became a part of Antara Newswire Agency, Adinegoro became Antara's Bureau Head of Education, Research and Documentation.

Among the press society, Adinegoro was known as a teacher who was very concerned about the youths. Adinegoro was one of the founders of Sekolah Tinggi Publisistik in Jakarta and Faculty of Publicity (now known as Faculty of Communication) at Padjadjaran University, Bandung.

Adinegoro's concern about the freedom of the press when political animosity increased affected his health. Several times his health was declining and Adinegoro had to be hospitalized in Carolus Hospital, Jakarta. On 8 January 1967 the Indonesian journalist died.[9] He now rests in Karet Bivak Public Cemetery in Central Jakarta.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Revolusi dan Kebudayaan (1954)

- Ensiklopedi Umum dalam Bahasa Indonesia (1954),

- Ilmu Karang-mengarang

- Falsafah Ratu Dunia

Novel

[edit]- Darah Muda. Batavia Centrum : Balai Pustaka. 1931

- Asmara Jaya. Batavia Centrum : Balai Pustaka. 1932.

- Melawat ke Barat. Jakarta : Balai Pustaka. 1950.

Short stories

[edit]- Bayati es Kopyor. Varia. No. 278. Th. Ke-6. 1961, hlm. 3—4, 32.

- Etsuko. Varia. No. 278. Th. Ke-6. 1961. hlm. 2—3, 31

- Lukisan Rumah Kami. Djaja. No. 83. Th. Ke-2. 1963. hlm. 17—18.

- Nyanyian Bulan April. Varia. No. 293. Th. Ke-6. 1963. hlm. 2–3 dan 31–32.

References

[edit]- ^ Anthony Reid (2005). An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and Other Histories of Sumatra. NUS Press. p. 34. ISBN 9971692988.

- ^ McMillan, Richard (2006). The British occupation of Indonesia 1945–1946. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-35551-6.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.iannnews.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Indonesians in Focus: Iwan Gayo – Daily – Daily, Indonesian News Indonesians in Focus. Planet Mole (2006-03-23). Retrieved on 2014-08-24.

- ^ Perpustakaan Universitas Diponegoro – Digital Library Diponegoro University Archived 2012-09-13 at the Wayback Machine. Digilib.undip.ac.id. Retrieved on 2014-08-24.

- ^ Ajen Dianawati (2004). Rpul Sd. Wahyu Media. pp. 263–. ISBN 978-979-3806-65-5.

- ^ Yasuhiro Kuroiwa (2012). "Military Mail for a Linguist: Soldiers Who Support and Profit from the Language Studies of Masamichi Miyatake" (PDF). Zinbun. 43: 35–50.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (October 1971). "The Birth of the Republic of Sumatra" (PDF). Indonesia. 12 (12): 21–46. doi:10.2307/3350656. JSTOR 3350656.

- ^ Marthias Dusky Pandoe (2010). Jernih melihat cermat mencatat: antologi karya jurnalistik wartawan senior Kompas. Penerbit Buku Kompas. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-979-709-487-4.