Mode locking

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (December 2021) |

Mode locking is a technique in optics by which a laser can be made to produce pulses of light of extremely short duration, on the order of picoseconds (10−12 s) or femtoseconds (10−15 s). A laser operated in this way is sometimes referred to as a femtosecond laser, for example, in modern refractive surgery. The basis of the technique is to induce a fixed phase relationship between the longitudinal modes of the laser's resonant cavity. Constructive interference between these modes can cause the laser light to be produced as a train of pulses. The laser is then said to be "phase-locked" or "mode-locked".

Laser cavity modes

[edit]

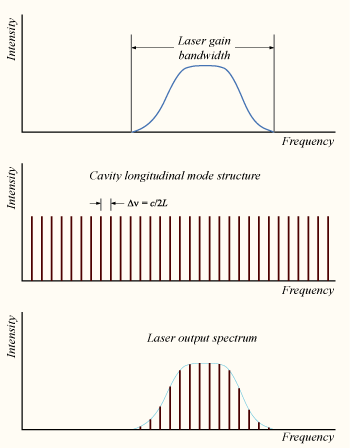

Although laser light is perhaps the purest form of light, it is not of a single, pure frequency or wavelength. All lasers produce light over some natural bandwidth or range of frequencies. A laser's bandwidth of operation is determined primarily by the gain medium from which the laser is constructed, and the range of frequencies over which a laser may operate is known as the gain bandwidth. For example, a typical helium–neon laser has a gain bandwidth of about 1.5 GHz (a wavelength range of about 0.002 nm at a central wavelength of 633 nm), whereas a titanium-doped sapphire (Ti:sapphire) solid-state laser has a bandwidth of about 128 THz (a 300 nm wavelength range centered at 800 nm).

The second factor to determine a laser's emission frequencies is the optical cavity (or resonant cavity) of the laser. In the simplest case, this consists of two plane (flat) mirrors facing each other, surrounding the gain medium of the laser (this arrangement is known as a Fabry–Pérot cavity). Since light is a wave, when bouncing between the mirrors of the cavity, the light constructively and destructively interferes with itself, leading to the formation of standing waves, or modes, between the mirrors. These standing waves form a discrete set of frequencies, known as the longitudinal modes of the cavity. These modes are the only frequencies of light that are self-regenerating and allowed to oscillate by the resonant cavity; all other frequencies of light are suppressed by destructive interference. For a simple plane-mirror cavity, the allowed modes are those for which the separation distance of the mirrors L is an exact multiple of half the wavelength of the light λ, such that L = qλ / 2, where q is an integer known as the mode order.

In practice, L is usually much greater than λ, so the relevant values of q are large (around 105 to 106). Of more interest is the frequency separation between any two adjacent modes q and q + 1; this is given (for an empty linear resonator of length L) by Δν = c / 2L, where c is the speed of light (≈ 3×108 m/s).

Using the above equation, a small laser with a mirror separation of 30 cm has a frequency separation between longitudinal modes of 0.5 GHz. Thus for the two lasers referenced above, with a 30 cm cavity, the 1.5 GHz bandwidth of the HeNe laser would support up to 3 longitudinal modes, whereas the 128 THz bandwidth of the Ti:sapphire laser could support approximately 250,000 modes. When more than one longitudinal mode is excited, the laser is said to be in "multi-mode" operation. When only one longitudinal mode is excited, the laser is said to be in "single-mode" operation.

Each individual longitudinal mode has some bandwidth or narrow range of frequencies over which it operates, but typically this bandwidth, determined by the Q factor of the cavity (see Fabry–Pérot interferometer), is much smaller than the intermode frequency separation.

Mode-locking theory

[edit]In a simple laser, each of these modes oscillates independently, with no fixed relationship between each other, in essence like a set of independent lasers, all emitting light at slightly different frequencies. The individual phase of the light waves in each mode is not fixed and may vary randomly due to such things as thermal changes in materials of the laser. In lasers with only a few oscillating modes, interference between the modes can cause beating effects in the laser output, leading to fluctuations in intensity; in lasers with many thousands of modes, these interference effects tend to average to a near-constant output intensity.

If instead of oscillating independently, each mode operates with a fixed phase between it and the other modes, then the laser output behaves quite differently. Instead of a random or constant output intensity, the modes of the laser will periodically all constructively interfere with one another, producing an intense burst or pulse of light. Such a laser is said to be "mode-locked" or "phase-locked". These pulses occur separated in time by τ = 2L/c, where τ is the time taken for the light to make exactly one round trip of the laser cavity. This time corresponds to a frequency exactly equal to the mode spacing of the laser, Δν = 1/τ.

The duration of each pulse of light is determined by the number of modes oscillating in phase (in a real laser, it is not necessarily true that all of the laser's modes are phase-locked). If there are N modes locked with a frequency separation Δν, then the overall mode-locked bandwidth is NΔν, and the wider this bandwidth, the shorter the pulse duration from the laser. In practice, the actual pulse duration is determined by the shape of each pulse, which is in turn determined by the exact amplitude and phase relationship of each longitudinal mode. For example, for a laser producing pulses with a Gaussian temporal shape, the minimum possible pulse duration Δt is given by

The value 0.441 is known as the "time–bandwidth product" of the pulse and varies depending on the pulse shape. For ultrashort-pulse lasers, a hyperbolic-secant-squared (sech2) pulse shape is often assumed, giving a time–bandwidth product of 0.315.

Using this equation, the minimum pulse duration can be calculated consistent with the measured laser spectral width. For the HeNe laser with a 1.5 GHz bandwidth, the shortest Gaussian pulse consistent with this spectral width is around 300 picoseconds; for the 128 THz bandwidth Ti:sapphire laser, this spectral width corresponds to a pulse of only 3.4 femtoseconds. These values represent the shortest possible Gaussian pulses consistent with the laser's bandwidth; in a real mode-locked laser, the actual pulse duration depends on many other factors, such as the actual pulse shape and the overall dispersion of the cavity.

Subsequent modulation could, in principle, shorten the pulse width of such a laser further; however, the measured spectral width would then be correspondingly increased.

Principle of phase and mode locking

[edit]There are many ways to lock frequency, but the basic principle is the same, which is based on the feedback loop of the laser system. The starting point of the feedback loop is the quantity that must be stabilized (frequency or phase). To check whether frequency changes with time, a reference is needed. A common way to measure laser frequency is to link it with a geometrical property of an optical cavity. The Fabry-Pérot cavity is most commonly used for this purpose, consisting of two parallel mirrors separated by some distance. This method is based on the fact that light can resonate and be transmitted only if the optical path length of a single round trip is an integral multiple of the wavelength of the light. Deviation of a laser's frequency from this condition will decrease transmission of that frequency. The relation between transmission and frequency deviation is given by a Lorentzian function with a full-width half-maximum line width

where ΔνFSR = c/2L is the frequency difference between adjacent resonances (i.e. the free spectral range) and F is the finesse,

where R is the reflectivity of mirrors. Therefore, to obtain a small cavity line width, mirrors must have higher reflectivity, so to reduce the line width of the laser to the lowest extent, a high finesse cavity is required.

Mode-locking methods

[edit]Methods for producing mode locking in a laser may be classified as either "active" or "passive". Active methods typically involve using an external signal to induce a modulation of the intracavity light. Passive methods do not use an external signal, but rely on placing some element into the laser cavity which causes self-modulation of the light.

Active mode locking

[edit]The most common active mode-locking technique places a standing wave electro-optic modulator into the laser cavity. When driven with an electrical signal, this produces a sinusoidal amplitude modulation of the light in the cavity. Considering this in the frequency domain, if a mode has optical frequency ν and is amplitude-modulated at a frequency f, then the resulting signal has sidebands at optical frequencies ν − f and ν + f. If the modulator is driven at the same frequency as the cavity mode spacing Δν, then these sidebands correspond to the two cavity modes adjacent to the original mode. Since the sidebands are driven in-phase, the central mode and the adjacent modes will be phase-locked together. Further operation of the modulator on the sidebands produces phase locking of the ν − 2f and ν + 2f modes, and so on until all modes in the gain bandwidth are locked. As said above, typical lasers are multi-mode and not seeded by a root mode, so multiple modes need to work out which phase to use. In a passive cavity with this locking applied, there is no way to dump the entropy given by the original independent phases. This locking is better described as a coupling, leading to a complicated behavior and not clean pulses. The coupling is only dissipative because of the dissipative nature of the amplitude modulation; otherwise, the phase modulation would not work.

This process can also be considered in the time domain. The amplitude modulator acts as a weak "shutter" to the light bouncing between the mirrors of the cavity, attenuating the light when it is "closed" and letting it through when it is "open". If the modulation rate f is synchronised to the cavity round-trip time τ, then a single pulse of light will bounce back and forth in the cavity. The actual strength of the modulation does not have to be large; a modulator that attenuates 1% of the light when "closed" will mode-lock a laser, since the same part of the light is repeatedly attenuated as it traverses the cavity.

Related to this amplitude modulation (AM), active mode locking is frequency-modulation (FM) mode locking, which uses a modulator device based on the acousto-optic effect. This device, when placed in a laser cavity and driven with an electrical signal, induces a small, sinusoidally varying frequency shift in the light passing through it. If the frequency of modulation is matched to the round-trip time of the cavity, then some light in the cavity sees repeated upshifts in frequency, and some repeated downshifts. After many repetitions, the upshifted and downshifted light is swept out of the gain bandwidth of the laser. The only light unaffected is that which passes through the modulator when the induced frequency shift is zero, which forms a narrow pulse of light.

The third method of active mode locking is synchronous mode locking, or synchronous pumping. In this, the pump source (energy source) for the laser is itself modulated, effectively turning the laser on and off to produce pulses. Typically, the pump source is itself another mode-locked laser. This technique requires accurately matching the cavity lengths of the pump laser and the driven laser.

Passive mode locking

[edit]Passive mode-locking techniques are those that do not require a signal external to the laser (such as the driving signal of a modulator) to produce pulses. Rather, they use the light in the cavity to cause a change in some intracavity element, which will then itself produce a change in the intracavity light. A commonly used device to achieve this is a saturable absorber.

A saturable absorber is an optical device that exhibits an intensity-dependent transmission, meaning that the device behaves differently depending on the intensity of the light passing through it. For passive mode locking, ideally a saturable absorber selectively absorbs low-intensity light, but transmits light of sufficiently high intensity. When placed in a laser cavity, a saturable absorber attenuates low-intensity constant-wave light (pulse wings). However, because of the somewhat random intensity fluctuations experienced by an un-mode-locked laser, any random, intense spike is transmitted preferentially by the saturable absorber. As the light in the cavity oscillates, this process repeats, leading to the selective amplification of the high-intensity spikes and the absorption of the low-intensity light. After many round trips, this leads to a train of pulses and mode locking of the laser.

Considering this in the frequency domain, if a mode has optical frequency ν and is amplitude-modulated at a frequency nf, then the resulting signal has sidebands at optical frequencies ν − nf and ν + nf and enables much stronger mode locking for shorter pulses and more stability than active mode locking, but has startup problems.

Saturable absorbers are commonly liquid organic dyes, but they can also be made from doped crystals and semiconductors. Semiconductor absorbers tend to exhibit very fast response times (~100 fs), which is one of the factors that determines the final duration of the pulses in a passively mode-locked laser. In a colliding-pulse mode-locked laser the absorber steepens the leading edge, while the lasing medium steepens the trailing edge of the pulse.

There are also passive mode-locking schemes that do not rely on materials that directly display an intensity-dependent absorption. In these methods, nonlinear optical effects in intracavity components are used to provide a method of selectively amplifying high-intensity light in the cavity and attenuation of low-intensity light. One of the most successful schemes is called Kerr-lens mode locking (KLM), also sometimes called "self-mode-locking". This uses a nonlinear optical process, the optical Kerr effect, which results in high-intensity light being focused differently from low-intensity light. By careful arrangement of an aperture in the laser cavity, this effect can be exploited to produce the equivalent of an ultra-fast response-time saturable absorber.

Hybrid mode locking

[edit]In some semiconductor lasers, a combination of the two above techniques can be used. Using a laser with a saturable absorber and modulating the electrical injection at the same frequency the laser is locked at, the laser can be stabilized by the electrical injection. This has the advantage of stabilizing the phase noise of the laser and can reduce the timing jitter of the pulses from the laser.

Mode locking by residual cavity fields

[edit]Coherent phase-information transfer between subsequent laser pulses has also been observed from nanowire lasers. Here, the phase information has been stored in the residual photon field of coherent Rabi oscillations in the cavity. Such findings open the way to phase locking of light sources integrated onto chip-scale photonic circuits and applications, such as on-chip Ramsey comb spectroscopy.[1]

Fourier-domain mode locking

[edit]Fourier-domain mode locking (FDML) is a laser mode-locking technique that creates a continuous-wave, wavelength-swept light output.[2] A main application for FDML lasers is optical coherence tomography.

Practical mode-locked lasers

[edit]In practice, a number of design considerations affect the performance of a mode-locked laser. The most important are the overall dispersion of the laser's optical resonator, which can be controlled with a prism compressor or some dispersive mirrors placed in the cavity, and optical nonlinearities. For excessive net group delay dispersion (GDD) of the laser cavity, the phase of the cavity modes can not be locked over a large bandwidth, and it will be difficult to obtain very short pulses. For a suitable combination of negative (anomalous) net GDD with the Kerr nonlinearity, soliton-like interactions may stabilize the mode locking and help to generate shorter pulses. The shortest possible pulse duration is usually accomplished either for zero dispersion (without nonlinearities) or for some slightly negative (anomalous) dispersion (exploiting the soliton mechanism).

The shortest directly produced optical pulses are generally produced by Kerr-lens mode-locked Ti:sapphire lasers and are around 5 femtoseconds long. Alternatively, amplified pulses of a similar duration are created through the compression of longer (e.g. 30 fs) pulses by self-phase modulation in a hollow-core fibre or during filamentation. However, the minimum pulse duration is limited by the period of the carrier frequency (which is about 2.7 fs for Ti:sapphire systems); therefore, shorter pulses require moving to shorter wavelengths. Some advanced techniques (involving high-harmonic generation with amplified femtosecond laser pulses) can be used to produce optical features with durations as short as 100 attoseconds in the extreme ultraviolet spectral region (i.e. <30 nm). Other achievements, important particularly for laser applications, concern the development of mode-locked lasers that can be pumped with laser diodes, can generate very high average output powers (tens of watts) in sub-picosecond pulses, or generate pulse trains with extremely high repetition rates of many GHz.

Pulse durations less than approximately 100 fs are too short to be directly measured using optoelectronic techniques (i.e. photodiodes), and so indirect methods, such as autocorrelation, frequency-resolved optical gating, spectral phase interferometry for direct electric-field reconstruction, and multiphoton intrapulse interference phase scan are used.

Applications

[edit]- Nuclear fusion (inertial confinement fusion).

- Nonlinear optics, such as second-harmonic generation, parametric down-conversion, optical parametric oscillators, and generation of terahertz radiation.

- Optical data storage uses lasers, and the emerging technology of 3D optical data storage generally relies on nonlinear photochemistry. For this reason, many examples use mode-locked lasers, since they can offer a very high repetition rate of ultrashort pulses.

- Femtosecond laser nanomachining – the short pulses can be used to nanomachine in many types of materials.

- An example of pico- and femtosecond micromachining is drilling the silicon jet surface of inkjet printers.

- Two-photon microscopy.

- Corneal surgery (see refractive surgery). Femtosecond lasers can be used to create bubbles in the cornea. A line of bubbles can be used to create a cut in the cornea, replacing the microkeratome, such as for the creation of a flap in LASIK surgery (this is sometimes referred to as Intralasik or all-laser surgery). Bubbles can also be created in multiple layers so that a piece of corneal tissue between these layers can be removed (a procedure known as small incision lenticule extraction).

- A laser technique has been developed that renders the surface of metals deep black. A femtosecond laser pulse deforms the surface of the metal, forming nanostructures. The immensely increased surface area can absorb virtually all the light that falls on it, thus rendering it deep black. This is one type of black gold.[3][4]

- Photonic sampling, using the high accuracy of lasers over electronic clocks to decrease the sampling error in electronic ADCs.

Locking mechanism of laser cavity

[edit]Monochromatic light is the property of the laser depends on the fundamental working principle of the laser which contains frequency-selective elements. For example, in diode lasers, external mirror resonators and gratings are those elements. With the help of these elements, frequency selection leads to a very narrow spectral emission of light. However, when observed closely, there are frequency fluctuations that occur on different time scales. There can be different reasons for their origin, such as fluctuation in input voltage, acoustic vibration, or change in pressure and temperature of the surroundings. So, to narrow down these frequency fluctuations, it is necessary to stabilize the phase or frequency of the laser to an external extent. Stabilizing laser properties using any external source or external reference is generally called "laser locking" or simply "locking".

Error signal generation

[edit]The reason for generation to create error signals is to create an electronic signal which is proportional to the laser's deviation from a particular set frequency or phase, which is called a "lock point". If the laser frequency is large, then the signal is positive; if frequency is very small, then the signal is negative. The point where the signal is zero is called a lock point. Laser locking based on an error signal which is a function of frequency is called frequency locking and if the error signal is a function of phase deviation of laser then this locking is referred to as phase locking. If the signal is created using an optical setup involving references like frequency references, then by using the reference, the optical signal is directly converted into frequencies which can be detected directly. The other way is to record the signal using a photodiode or camera and further change this signal electronically.

See also

[edit]- Disk laser

- Dissipative soliton

- Femtotechnology

- Fiber laser

- Frequency comb

- Laser construction

- Q-switching

- Saturable absorption

- Solid state laser

- Soliton

- Ultrafast optics

- Vector soliton

References

[edit]- ^ Mayer, B., et al. "Long-term mutual phase locking of picosecond pulse pairs generated by a semiconductor nanowire laser". Nature Communications 8 (2017): 15521.

- ^ R. Huber, M. Wojtkowski, J. G. Fujimoto, "Fourier Domain Mode Locking (FDML): A new laser operating regime and applications for optical coherence tomography", Opt. Express 14, 3225–3237 (2006).

- ^ "Ultra-Intense Laser Blast Creates True 'Black Metal'". Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Vorobyev, A. Y.; Guo, Chunlei (28 January 2008). "Colorizing metals with femtosecond laser pulses". Applied Physics Letters. 92 (4): 041914. Bibcode:2008ApPhL..92d1914V. doi:10.1063/1.2834902.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrew M. Weiner (2009). Ultrafast Optics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-41539-8.

- H. Zhang et al, “Induced solitons formed by cross polarization coupling in a birefringent cavity fiber laser”, Opt. Lett., 33, 2317–2319.(2008).

- D.Y. Tang et al, “Observation of high-order polarization-locked vector solitons in a fiber laser”, Physical Review Letters, 101, 153904 (2008).

- H. Zhang et al., "Coherent energy exchange between components of a vector soliton in fiber lasers", Optics Express, 16,12618–12623 (2008).

- H. Zhang et al, “Multi-wavelength dissipative soliton operation of an erbium-doped fiber laser”, Optics Express, Vol. 17, Issue 2, pp. 12692–12697

- L.M. Zhao et al, “Polarization rotation locking of vector solitons in a fiber ring laser”, Optics Express, 16,10053–10058 (2008).

- Qiaoliang Bao, Han Zhang, Yu Wang, Zhenhua Ni, Yongli Yan, Ze Xiang Shen, Kian Ping Loh, and Ding Yuan Tang, Advanced Functional Materials,"Atomic layer graphene as saturable absorber for ultrafast pulsed lasers "

- Zhang, H.; et al. (2010). "Graphene mode locked, wavelength-tunable, dissipative soliton fiber laser" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 96 (11): 111112. arXiv:1003.0154. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..96k1112Z. doi:10.1063/1.3367743. S2CID 119233725. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011.