Hunger

In politics, humanitarian aid, and the social sciences, hunger is defined as a condition in which a person does not have the physical or financial capability to eat sufficient food to meet basic nutritional needs for a sustained period. In the field of hunger relief, the term hunger is used in a sense that goes beyond the common desire for food that all humans experience, also known as an appetite. The most extreme form of hunger, when malnutrition is widespread, and when people have started dying of starvation through lack of access to sufficient, nutritious food, leads to a declaration of famine.[2]

Throughout history, portions of the world's population have often suffered sustained periods of hunger. In many cases, hunger resulted from food supply disruptions caused by war, plagues, or adverse weather. In the decades following World War II, technological progress and enhanced political cooperation suggested it might be possible to substantially reduce the number of people suffering from hunger. While progress was uneven, by 2015, the threat of extreme hunger had receded for a large portion of the world's population. According to the FAO's 2023 The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, this positive trend had reversed from about 2017, when a gradual rise in number of people suffering from chronic hunger became discernible. In 2020 and 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increase in the number of people suffering from undernourishment. A recovery occurred in 2022 along with the economic rebound, though the impact on global food markets caused by the invasion of Ukraine meant the reduction in world hunger was limited.[3]

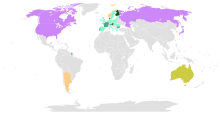

While most of the world's people continue to live in Asia, much of the increase in hunger since 2017 occurred in Africa and South America. The FAO's 2017 report discussed three principal reasons for the recent increase in hunger: climate, conflict, and economic slowdowns. The 2018 edition focused on extreme weather as a primary driver of the increase in hunger, finding rising rates to be especially severe in countries where agricultural systems were most sensitive to extreme weather variations. The 2019 SOFI report found a strong correlation between increases in hunger and countries that had suffered an economic slowdown. The 2020 edition instead looked at the prospects of achieving the hunger related Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). It warned that if nothing was done to counter the adverse trends of the past six years, the number of people suffering from chronic hunger could rise by over 150 million by 2030. The 2023 report reported a sharp jump in hunger caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which leveled off in 2022.

Many thousands of organizations are engaged in the field of hunger relief, operating at local, national, regional, or international levels. Some of these organizations are dedicated to hunger relief, while others may work in several different fields. The organizations range from multilateral institutions to national governments, to small local initiatives such as independent soup kitchens. Many participate in umbrella networks that connect thousands of different hunger relief organizations. At the global level, much of the world's hunger relief efforts are coordinated by the UN and geared towards achieving SDG 2 of Zero Hunger by 2030.

Definition and related terms

[edit]There is one globally recognized approach for defining and measuring hunger generally used by those studying or working to relieve hunger as a social problem. This is the United Nation's FAO measurement, which is typically referred to as chronic undernourishment (or in older publications, as 'food deprivation,' 'chronic hunger,' or just plain 'hunger.') For the FAO:

- Hunger or chronic undernourishment exists when "caloric intake is below the minimum dietary energy requirement (MDER). The MDER is the amount of energy needed to perform light activity and to maintain a minimum acceptable weight for attained height."[4] The FAO use different MDER thresholds for different countries, due to variations in climate and cultural factors. Typically a yearly "balance sheet" approach is used, with the minimum dietary energy requirement tallied against the estimated total calories consumed over the year. The FAO definitions differentiate hunger from malnutrition and food insecurity:[5][6][7]

- Malnutrition results from "deficiencies, excesses or imbalances in the consumption of macro- and/or micro-nutrients." In the FAO definition, all hungry people suffer from malnutrition, but people who are malnourished may not be hungry. They may get sufficient raw calories to avoid hunger but lack essential micronutrients, or they may even consume an excess of raw calories and hence suffer from obesity.[7][6][5]

- Food insecurity occurs when people are at risk, or worried about, not being able to meet their preferences for food, including in terms of raw calories and nutritional value. In the FAO definition, all hungry people are food insecure, but not all food-insecure people are hungry (though there is a very strong overlap between hunger and severe food insecurity.). The FAO have reported that food insecurity quite often results in simultaneous stunted growth for children, and obesity for adults. For hunger relief actors operating at the global or regional level, an increasingly commonly used metric for food insecurity is the IPC scale.[7][6][5]

- Acute hunger is typically used to denote famine like hunger, though the phrase lacks a widely accepted formal definition. In the context of hunger relief, people experiencing 'acute hunger' may also suffer from 'chronic hunger'. The word is used mainly to denote severity, not long-term duration.[7][8][5]

Not all of the organizations in the hunger relief field use the FAO definition of hunger. Some use a broader definition that overlaps more fully with malnutrition. The alternative definitions do however tend to go beyond the commonly understood meaning of hunger as a painful or uncomfortable motivational condition; the desire for food is something that all humans frequently experience, even the most affluent, and is not in itself a social problem.[9][7][6][5]

Very low food supply can be described as "food insecure with hunger." A change in description was made in 2006 at the recommendation of the Committee on National Statistics (National Research Council, 2006) in order to distinguish the physiological state of hunger from indicators of food availability.[10] Food insecure is when food intake of one or more household members was reduced and their eating patterns were disrupted at times during the year because the household lacked money and other resources for food.[10] Food security statistics is measured by using survey data, based on household responses to items about whether the household was able to obtain enough food to meet their needs.[11]

World statistics

[edit]

The United Nations publishes an annual report on the state of food security and nutrition across the world. Led by the FAO, the report was joint authored by four other UN agencies: the WFP, IFAD, WHO and UNICEF. The theme of the 2024 report is on how efforts to meet SDG 2.1 & 2.2 can be financed. The FAO's yearly report provides a statistical overview on the prevalence of hunger around the world, and is widely considered the main global reference for tracking hunger. No simple set of statistics can ever fully capture the multi dimensional nature of hunger however. Reasons include that the FAO's key metric for hunger, "undernourishment", is defined solely in terms of dietary energy availability – disregarding micro-nutrients such as vitamins or minerals. Second, the FAO uses the energy requirements for minimum activity levels as a benchmark; many people would not count as hungry by the FAO's measure yet still be eating too little to undertake hard manual labour, which might be the only sort of work available to them. Thirdly, the FAO statistics do not always reflect short-term undernourishment.[6][12][13][14][3][15]

| Year | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (million) of undernourished people (global)[15] | 798.3 | 604.8 | 570.2 | 541.3 | 557.0 | 581.3 | 669.3 | 708.7 | 723.8 | 733.4 |

| Percentage of undernourished people (global)[15] | 12.2% | 8.7% | 7.7% | 7.1% | 7.2% | 7.5% | 8.5% | 9.0% | 9.1% | 9.1% |

An alternative measure of hunger across the world is the Global Hunger Index (GHI). Unlike the FAO's measure, the GHI defines hunger in a way that goes beyond raw calorie intake, to include for example ingestion of micronutrients. GDI is a multidimensional statistical tool used to describe the state of countries' hunger situation. The GHI measures progress and failures in the global fight against hunger.[16] The GHI is updated once a year. The data from the 2015 report showed that Hunger levels have dropped 27% since 2000. Fifty two countries remained at serious or alarming levels.[17] The 2019 GHI report expresses concern about the increase in hunger since 2015. In addition to the latest statistics on Hunger and Food Security, the GHI also features different special topics each year. The 2019 report includes an essay on hunger and climate change, with evidence suggesting that areas most vulnerable to climate change have suffered much of the recent increases in hunger.[18][19]

The fight against hunger

[edit]Pre World War II

[edit]

Throughout history, the need to aid those suffering from hunger has been commonly, though not universally,[20] recognized. The philosopher Simone Weil wrote that feeding the hungry when you have resources to do so is the most obvious of all human obligations. She says that as far back as Ancient Egypt, many believed that people had to show they had helped the hungry in order to justify themselves in the afterlife. Weil writes that Social progress is commonly held to be first of all, "...a transition to a state of human society in which people will not suffer from hunger."[21] Social historian Karl Polanyi wrote that before markets became the world's dominant form of economic organization in the 19th century, most human societies would either starve all together or not at all, because communities would invariably share their food.[22]

While some of the principles for avoiding famines had been laid out in the first book of the Bible,[23] they were not always understood. Historical hunger relief efforts were often largely left to religious organizations and individual kindness. Even up to early modern times, political leaders often reacted to famine with bewilderment and confusion. From the first age of globalization, which began in the 19th century, it became more common for the elite to consider problems like hunger in global terms. However, as early globalization largely coincided with the high peak of influence for classical liberalism, there was relatively little call for politicians to address world hunger.[24][25]

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the view that politicians ought not to intervene against hunger was increasingly challenged by campaigning journalists. There were also more frequent calls for large scale intervention against world hunger from academics and politicians, such as U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. Funded both by the government and private donations, the U.S. was able to dispatch millions of tons of food aid to European countries during and in the years immediately after WWI, organized by agencies such as the American Relief Administration. Hunger as an academic and social topic came to further prominence in the U.S. thanks to mass media coverage of the issue as a domestic problem during the Great Depression.[26][27][28][29][1][30]

Efforts after World War II

[edit]While there had been increasing attention to hunger relief from the late 19th century, Dr David Grigg has summarised that prior to the end of World War II, world hunger still received relatively little academic or political attention; whereas after 1945 there was an explosion of interest in the topic.[28]

After World War II, a new international politico-economic order came into being, which was later described as Embedded liberalism. For at least the first decade after the war, the United States, then by far the period's most dominant national actor, was strongly supportive of efforts to tackle world hunger and to promote international development. It heavily funded the United Nation's development programmes, and later the efforts of other multilateral organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB).[28][1][31]

The newly established United Nations became a leading player in co-ordinating the global fight against hunger. The UN has three agencies that work to promote food security and agricultural development: the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). FAO is the world's agricultural knowledge agency, providing policy and technical assistance to developing countries to promote food security, nutrition and sustainable agricultural production, particularly in rural areas. WFP's key mission is to deliver food into the hands of the hungry poor. The agency steps in during emergencies and uses food to aid recovery after emergencies. Its longer term approaches to hunger helps the transition from recovery to development. IFAD, with its knowledge of rural poverty and exclusive focus on poor rural people, designs and implements programmes to help those people access the assets, services and opportunities they need to overcome poverty.[28][1][31]

Following successful post WWII reconstruction of Germany and Japan, the IMF and WB began to turn their attention to the developing world. A great many civil society actors were also active in trying to combat hunger, especially after the late 1970s when global media began to bring the plight of starving people in places like Ethiopia to wider attention. Most significant of all, especially in the late 1960s and 70s, the Green revolution helped improved agricultural technology propagate throughout the world.[28][1][31]

The United States began to change its approach to the problem of world hunger from about the mid 1950s. Influential members of the administration became less enthusiastic about methods they saw as promoting an over reliance on the state, as they feared that might assist the spread of communism. By the 1980s, the previous consensus in favour of moderate government intervention had been displaced across the western world. The IMF and World Bank in particular began to promote market-based solutions. In cases where countries became dependent on the IMF, they sometimes forced national governments to prioritize debt repayments and sharply cut public services. This sometimes had a negative effect on efforts to combat hunger.[32][33][34]

Organizations such as Food First raised the issue of food sovereignty and claimed that every country on earth (with the possible minor exceptions of some city-states) has sufficient agricultural capacity to feed its own people, but that the "free trade" economic order, which from the late 1970s to about 2008 had been associated with such institutions as the IMF and World Bank, had prevented this from happening. The World Bank itself claimed it was part of the solution to hunger, asserting that the best way for countries to break the cycle of poverty and hunger was to build export-led economies that provide the financial means to buy foodstuffs on the world market. However, in the early 21st century the World Bank and IMF became less dogmatic about promoting free market reforms. They increasingly returned to the view that government intervention does have a role to play, and that it can be advisable for governments to support food security with policies favourable to domestic agriculture, even for countries that do not have a comparative advantage in that area. As of 2012, the World Bank remains active in helping governments to intervene against hunger.[35][28][1][31][36]

Until at least the 1980s—and, to an extent, the 1990s—the dominant academic view concerning world hunger was that it was a problem of demand exceeding supply. Proposed solutions often focused on boosting food production, and sometimes on birth control. There were exceptions to this, even as early as the 1940s, Lord Boyd-Orr, the first head of the UN's FAO, had perceived hunger as largely a problem of distribution, and drew up comprehensive plans to correct this. Few agreed with him at the time, however, and he resigned after failing to secure support for his plans from the US and Great Britain. In 1998, Amartya Sen won a Nobel Prize in part for demonstrating that hunger in modern times is not typically the product of a lack of food. Rather, hunger usually arises from food distribution problems, or from governmental policies in the developed and developing world. It has since been broadly accepted that world hunger results from issues with the distribution as well as the production of food.[32][33][34] Sen's 1981 essay Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation played a prominent part in forging the new consensus.[1][37]

In 2007 and 2008, rapidly increasing food prices caused a global food crisis. Food riots erupted in several dozen countries; in at least two cases, Haiti and Madagascar, this led to the toppling of governments. A second global food crisis unfolded due to the spike in food prices of late 2010 and early 2011. Fewer food riots occurred, due in part to greater availability of food stock piles for relief. However, several analysts argue the food crisis was one of the causes of the Arab Spring.[31][38][39]

Efforts since the global 2008 crisis

[edit]

In the early 21st century, the attention paid to the problem of hunger by the leaders of advanced nations such as those that form the G8 had somewhat subsided.[38] Prior to 2009, large scale efforts to fight hunger were mainly undertaken by governments of the worst affected countries, by civil society actors, and by multilateral and regional organizations. In 2009, Pope Benedict published his third encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, which emphasised the importance of fighting against hunger. The encyclical was intentionally published immediately before the July 2009 G8 Summit to maximise its influence on that event. At the Summit, which took place at L'Aquila in central Italy, the L'Aquila Food Security Initiative was launched, with a total of US$22 billion committed to combat hunger.[40][41]

Food prices fell sharply in 2009 and early 2010, though analysts credit this much more to farmers increasing production in response to the 2008 spike in prices, than to the fruits of enhanced government action. However, since the 2009 G8 summit, the fight against hunger became a high-profile issue among the leaders of the worlds major nations and was a prominent part of the agenda for the 2012 G-20 summit.[38][42][43]

In April 2012, the Food Assistance Convention was signed, the world's first legally binding international agreement on food aid. The May 2012 Copenhagen Consensus recommended that efforts to combat hunger and malnutrition should be the first priority for politicians and private sector philanthropists looking to maximize the effectiveness of aid spending. They put this ahead of other priorities, like the fight against malaria and AIDS.[44] Also in May 2012, U.S. President Barack Obama launched a "new alliance for food security and nutrition"—a broad partnership between private sector, governmental and civil society actors—that aimed to "...achieve sustained and inclusive agricultural growth and raise 50 million people out of poverty over the next 10 years."[32][42][45][46] The UK's prime minister David Cameron held a hunger summit on 12 August, the last day of the 2012 Summer Olympics.[42]

The fight against hunger has also been joined by an increased number of regular people. While folk throughout the world had long contributed to efforts to alleviate hunger in the developing world, there has recently been a rapid increase in the numbers involved in tackling domestic hunger even within the economically advanced nations of the Global North. This had happened much earlier in North America than it did in Europe. In the US, the Reagan administration scaled back welfare the early 1980s, leading to a vast increase of charity sector efforts to help Americans unable to buy enough to eat. According to a 1992 survey of 1000 randomly selected US voters, 77% of Americans had contributed to efforts to feed the hungry, either by volunteering for various hunger relief agencies such as food banks and soup kitchens, or by donating cash or food.[47] Europe, with its more generous welfare systems, had little awareness of domestic hunger until the food price inflation that began in late 2006, and especially as austerity-imposed welfare cuts began to take effect in 2010. Various surveys reported that upwards of 10% of Europe's population had begun to suffer from food insecurity. Especially since 2011, there has been a substantial increase in grass roots efforts to help the hungry by means of food banks, both in the UK and in continental Europe.[48][49][50][51][52]

By July 2012, the 2012 US drought had already caused a rapid increase in the price of grain and soy, with a knock on effect on the price of meat. As well as affecting hungry people in the US, this caused prices to rise on the global markets; the US is the world's biggest exporter of food. This led to much talk of a possible third 21st century global food crisis. The Financial Times reported that the BRICS may not be as badly affected as they were in the earlier crises of 2008 and 2011. However, smaller developing countries that must import a substantial portion of their food could be hard hit. The UN and G20 has begun contingency planning so as to be ready to intervene if a third global crisis breaks out.[35][39][53][54] By August 2013 however, concerns had been allayed, with above average grain harvests expected from major exporters, including Japan, Brazil, Ukraine and the US.[55] 2014 also saw a good worldwide harvest, leading to speculation that grain prices could soon begin to fall.[56]

In an April 2013 summit held in Dublin concerning Hunger, Nutrition, Climate Justice, and the post 2015 MDG framework for global justice, Ireland's President Higgins said that only 10% of deaths from hunger are due to armed conflict and natural disasters, with ongoing hunger being both the "greatest ethical failure of the current global system" and the "greatest ethical challenge facing the global community."[57] $4.15 billion of new commitments were made to tackle hunger at a June 2013 Hunger Summit held in London, hosted by the governments of Britain and Brazil, together with The Children's Investment Fund Foundation.[58][59]

Despite the hardship caused by the 2007–2009 financial crisis and global increases in food prices that occurred around the same time, the UN's global statistics show it was followed by close to year on year reductions in the numbers suffering from hunger around the world. By 2019 however, evidence had mounted that this progress seemed to have gone into reverse over the last four years. The numbers suffering from hunger had risen both in absolute terms and very slightly even as a percentage of the world's population.[60][61][12]

In 2019, FAO its annual edition of The State of Food and Agriculture which asserted that food loss and waste has potential effects on food security and nutrition through changes in the four dimensions of food security: food availability, access, utilization and stability. However, the links between food loss and waste reduction and food security are complex, and positive outcomes are not always certain. Reaching acceptable levels of food security and nutrition inevitably implies certain levels of food loss and waste. Maintaining buffers to ensure food stability requires a certain amount of food to be lost or wasted. At the same time, ensuring food safety involves discarding unsafe food, which then is counted as lost or wasted, while higher-quality diets tend to include more highly perishable foods. How the impacts on the different dimensions of food security play out and affect the food security of different population groups depends on where in the food supply chain the reduction in losses or waste takes place as well as on where nutritionally vulnerable and food-insecure people are located geographically.[62]

In April and May 2020, concerns were expressed that the COVID-19 pandemic could result in a doubling in global hunger unless world leaders acted to prevent this. Agencies such as the WFP warned that this could include the number of people facing acute hunger rising from 135 million to about 265 million by the end of 2020. Indications of extreme hunger were seen in various cities, such as fatal stampedes when word spread that emergency food aid was being handed out. Letters calling for co-ordinated action to offset the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were written to the G20 and G7, by various actors including NGOs, UN staff, corporations, academics and former national leaders.[63][64] [65] [8] The FAO found that 122 million more people experienced hunger in 2022 compared to 2019.[66] Following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, concerns have been raised over hunger resulting from rising food prices. This is forecast to risk civil unrest even in many middle income countries, where government capability to protect their populations was largely exhausted by the Covid pandemic, and has not yet recovered.[67]

Hunger relief organisations

[edit]Many thousands of hunger relief organisations exist across the world. Some but not all are entirely dedicated to fighting hunger. They range from independent soup kitchens that serve only one locality, to global organisations. Organisations working at the global and regional level will often focus much of their efforts on helping hungry communities to better feed themselves, for example by sharing agricultural technology. With some exceptions, organisations that work just on the local level tend to focus more on providing food directly to hungry people. Many of the entities are connected by a web of national, regional and global alliances that help them share resources, knowledge, and coordinate efforts.[68]

Global

[edit]The United Nations is central to global efforts to relieve hunger, most especially through the FAO, and also via other agencies: such as WFP, IFAD, WHO and UNICEF. After the Millennium Development Goals expired in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) became key objectives to shape the world's response to development challenges such as hunger. In particular Goal 2: Zero Hunger sets globally agreed targets to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.[69][7][8]

Aside from the UN agencies themselves, hundreds of other actors address the problem of hunger on the global level, often involving participation in large umbrella organisations. These include national governments, religious groups, international charities and in some cases international corporations. Though except perhaps in the cases of dedicated charities, the priority these organisations assign to hunger relief may vary from year to year. In many cases the organisations partner with the UN agencies, though often they pursue independent goals. For example, as consensus began to form for the SDG zero hunger goal to aim to end hunger by 2030, a number of organizations formed initiatives with the more ambitious target to achieve this outcome early, by 2025:

- In 2013 Caritas International started a Caritas-wide initiative aimed at ending systemic hunger by 2025. The One human family, food for all campaign focuses on awareness raising, improving the impact of Caritas programs and advocating the implementation of the right to food.[70]

- The partnership Compact2025, led by IFPRI with the involvement of UN organisations, NGOs and private foundations[71] develops and disseminates evidence-based advice to politicians and other decision-makers aimed at ending hunger and undernutrition in the coming 10 years, by 2025.[72] It bases its claim that hunger can be ended by 2025 on a report by Shenggen Fan and Paul Polman that analyzed the experiences from Russia, China, Vietnam, Brazil and Thailand and concludes that eliminating hunger and undernutrition was possible by 2025.[73]

- In June 2015, the European Union and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation launched a partnership to combat undernutrition especially in children. The program would initially be implemented in Bangladesh, Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos and Niger and will help these countries to improve information and analysis about nutrition so they can develop effective national nutrition policies.[74]

Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2 or Goal 2)

[edit]The objective of SDG 2 is to "end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture" by 2030. SDG2 recognizes that dealing with hunger is not only based on increasing food production but also on proper markets, access to land and technology and increased and efficient incomes for farmers.[75]

A report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) of 2013 argued that the emphasis of the SDGs should be on eliminating hunger and under-nutrition, rather than on poverty, and that attempts should be made to do so by 2025 rather than 2030.[73] The argument is based on an analysis of experiences in Russia, China, Vietnam, Brazil, and Thailand and the fact that people suffering from severe hunger face extra impediments to improving their lives, whether it be by education or work. Three pathways to achieve this were identified: 1) agriculture-led; 2) social protection- and nutrition- intervention-led; or 3) a combination of both of these approaches.[73]

Regional

[edit]Much of the world's regional alliances are located in Africa. For example, the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa or the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.[76][68]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN has created a partnership that will act through the African Union's CAADP framework aiming to end hunger in Africa by 2025. It includes different interventions including support for improved food production, a strengthening of social protection and integration of the right to food into national legislation.[77]

National

[edit]

Examples of hunger relief organisations that operate on the national level include The Trussell Trust in the United Kingdom, the Nalabothu Foundation in India, and Feeding America in the United States.[78]

Local

[edit]Food bank

[edit]A food bank (or foodbank) is a non-profit, charitable organization that aids in the distribution of food to those who have difficulty purchasing enough to avoid hunger. Food banks tend to run on different operating models depending on where they are located. In the U.S., Australia, and to some extent in Canada, foodbanks tend to perform a warehouse type function, storing and delivering food to front line food orgs, but not giving it directly to hungry peoples themselves. In much of Europe and elsewhere, food banks operate on the front line model, where they hand out parcels of uncooked food direct to the hungry, typically giving them enough for several meals which they can eat in their homes. In the U.S and Australia, establishments that hand out uncooked food to individual people are instead called food pantries, food shelves or food closets'.[79]

In Less Developed Countries, there are charity-run food banks that operate on a semi-commercial system that differs from both the more common "warehouse" and "frontline" models. In some rural LDCs such as Malawi, food is often relatively cheap and plentiful for the first few months after the harvest, but then becomes more and more expensive. Food banks in those areas can buy large amounts of food shortly after the harvest, and then as food prices start to rise, they sell it back to local people throughout the year at well below market prices. Such food banks will sometimes also act as centers to provide small holders and subsistence farmers with various forms of support.[80]

Soup kitchen

[edit]

A soup kitchen, meal center, or food kitchen is a place where food is offered to the hungry for free or at a below market price. Frequently located in lower-income neighborhoods, they are often staffed by volunteer organizations, such as church or community groups. Soup kitchens sometimes obtain food from a food bank for free or at a low price, because they are considered a charity, which makes it easier for them to feed the many people who require their services.

Others

[edit]Local establishments calling themselves "food banks" or "soup kitchens" are often run either by Christian churches or less frequently by secular civil society groups. Other religions carry out similar hunger relief efforts, though sometimes with slightly different methods. For example, in the Sikh tradition of Langar, food is served to the hungry direct from Sikh temples. There are exceptions to this, for example in the UK Sikhs run some of the food banks, as well as giving out food direct from their Gurdwaras.[81][82]

Hunger and gender

[edit]

World Bank studies consistently find that about 60% of those who are hungry are female. Globally, women typically face greater economic barriers compared to men and have access to fewer resources, creating greater obstacles to food security. In both developing and advanced countries, parents sometimes go without food so they can feed their children. Women, however, seem more likely to make this sacrifice than men. Older sources sometimes claim this phenomenon is unique to developing countries, due to greater sexual inequality. More recent findings suggested that mothers often miss meals in advanced economies too. For example, a 2012 study undertaken by Netmums in the UK found that one in five mothers sometimes misses out on food to save their children from hunger.[35][83][84]

One partner-households are especially vulnerable to food insecurity and highlight a gender disparity in food security. In the U.S., households with children raised by single-mothers are more likely to be food insecure compared to households with single-fathers.[85] Differences in time allocation between paid work and unpaid work may also be an explanation for increased food disparity in women-lead households, as women tend to dedicate more time to unpaid work comparatively.[86]

In several periods and regions, gender has also been an important factor determining whether or not victims of hunger would make suitable examples for generating enthusiasm for hunger relief efforts. James Vernon, in his Hunger: A Modern History, wrote that in Britain before the twentieth century, it was generally only women and children suffering from hunger who could arouse compassion. Men who failed to provide for themselves and their families were often regarded with contempt.[27]

This changed after World War I, where thousands of men who had proved their manliness in combat found themselves unable to secure employment. Similarly, female gender could be advantageous for those wishing to advocate for hunger relief, with Vernon writing that being a woman helped Emily Hobhouse draw the plight of hungry people to wider attention during the Second Boer War.[27]

Hunger and age

[edit]United States

[edit]The elderly have an increased risk of going hungry as well as increased negative effects of hunger. In the US the number of seniors experiencing hunger rose 88% between 2001 and 2011.[87]

This age group suffers the most from chronic conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory diseases. Eighty percent of this group has a minimum of one chronic condition, and almost 70% have two or more.[88] These illnesses are exacerbated and are more likely to develop under the addition of hunger. A report from 2017 shows that seniors facing this issue are 60% more likely to experience depression than seniors who are not hungry, and 40% are more likely to develop congestive heart failure. The added stress of inconsistent and inadequate feedings make these conditions much more dangerous.[89]

Fixed incomes often limit the elderly's ability to freely purchase food necessities.[citation needed] Medical costs and housing may take priority over quality foods. Limited mobility makes it difficult for these individuals to physically leave their homes, especially in areas lacking public transportation or transportation catering to a disabled body.[citation needed] The COVID-19 pandemic made things more difficult, older people statistically suffer worse outcomes, and so could be reluctant to venture out for food.[citation needed]

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides aid to low-income seniors in relation to food security. This is an opportunity for seniors who receive benefits to allocate money in their budgets for other needs, such as medical or housing bills. However, participation is extremely low. Fewer than half of eligible seniors are enrolled and receive benefits; 3 out of five seniors are qualified but not enrolled.[90]

See also

[edit]- Action Against Hunger

- A Place at the Table

- Basic income

- Category:Hunger relief organizations

- Donation

- Economic issues

- Famine

- Famine relief

- Famine scales

- Feeding America

- Fome Zero (Hunger 0)

- Food Bank

- Food Donation Connection

- Food Matters

- Food production

- Global Hunger Index

- Homelessness

- Human rights

- Hunger in the United Kingdom

- Hunger in the United States

- Hunger marches

- The Hunger Project

- Income inequality

- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification

- Malnutrition

- Muselmann

- National Security Study Memorandum 200 (1974)

- Oxfam

- Poverty trap

- Project Open Hand

- Right to food

- Social programs

- Soup kitchen

- Starvation

- Starvation response

- United Nations Millennium Declaration

- Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition (1974)

- 2007–08 world food price crisis

Sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief, 24, FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief, 24, FAO, FAO.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g William A Dando, ed. (2012). "passim, see esp Introduction; Historiography of Food, Hunger and famine; Hunger and Starvation". Food and Famine in the 21st Century: Vol 1, Topics and Issues. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-730-7.

- ^ "Famine Prevention". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ a b "The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023" (PDF). FAO. 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "FAO Statistical Yearbook 2012: Part 2 Hunger dimensions" (PDF). FAO. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Patrick Webb, Gunhild Anker Stordalen, Sudhvir Singh, Ramani Wijesinha-Bettoni, Prakash Shetty, Anna Lartey (2018). "Hunger and malnutrition in the 21st century". The BMJ. 350: k2238. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2238. PMC 5996965. PMID 29898884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "The state of food security and nutrition in the world (2018)" (PDF). FAO. 11 September 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security" (PDF). FAO. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ a b c "2020GLOBAL REPORT ON FOOD CRISES" (PDF). Food Security Information Network. April 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Holben, David, H. (2005), "The Concept and Definition of Hunger and Its Relationship to Food Insecurity", National Academies of Science

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Coleman-Jensen. "Household Food Security in the United States in 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ Coleman-Jensen. "Household Food Security in the United states in 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ a b "The state of food security and nutrition in the world (2019)" (PDF). FAO. 15 July 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. FAO. 7 July 2020. doi:10.4060/CA9692EN. ISBN 978-92-5-132901-6. S2CID 239729231. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021" (PDF). FAO. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023". FAO. 2024. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "Global hunger worsening, warns UN". BBC (Europe). 14 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ K. von Grebmer, J. Bernstein, A. de Waal, N. Prasai, S. Yin, Y. Yohannes: 2015 Global Hunger Index - Armed Conflict and the Challenge of Hunger. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin: Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide. October 2015.

- ^ Lucy Lamble (15 October 2019). "Higher temperatures driving 'alarming' levels of hunger – report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ K. von Grebmer, J. Bernstein, R. Mukerji, F. Patterson, M. Wiemers, R. Ní Chéilleachair, C. Foley, S. Gitter, K. Ekstrom, and H. Fritschel. 2019. 2019 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger and Climate Change. Archived 23 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine Bonn: Welthungerhilfe; and Dublin: Concern Worldwide.

- ^ As an example of historical opposition to food aid, during the Hungry Forties, English Laissez-faire advocates were largely successful in preventing it being deployed by Great Britain to relief the Irish famine; see for example the section on "Ideology and relief"' in Chpt. 2 of The Great Irish Famine by Cormac Ó Gráda. For a detailed description of how views opposed to hunger relief became dominant within Great Britain's policy making circles during the 19th century, and also their subsequent displacement, see Hunger: A Modern History (2007) by James Vernon, esp. Chpts. 1–3. In 2012, advocates of small government spoke out against the US food stamp programme, saying it discourages people from fending for themselves, in the same way as it is not always a good idea to feed hungry wild animals. ( See Food stamp debate brings out the haters Archived 23 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine published by the Star Telegram. )

- ^ Simone Weil (2002) [1942]. The Need for Roots. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 0-415-27102-9.

- ^ Karl Polanyi (2002) [1942]. "chpt. 4". The Great Transformation. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5643-1.

- ^ See the story of Jacob and the seven years of plenty, seven years of famine: Genesis 41 Archived 20 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For further info see Hunger in the United Kingdom#Attitudes towards hunger relief.

- ^ There were many exceptions. For example, in Hunger: A Modern History (2007), James Vernon describes dozens of 18th and 19th century campaigners who spoke in favor of hunger relief.

- ^ As many individuals struggled for food, the same agricultural industries were suddenly producing large surpluses as means of increased production to counter the drop in demand from the European markets. This increased output was meant to ease the growing debt levels, however domestic demand could not keep up with prices. Instead, what is often called "the paradox of want amid plenty," agricultural surpluses and large demand simply did not fit together, causing the Hoover administration to buy large amounts of product, such as grain, to stabilize prices. Initially refusing to further compromise the distressed price levels, political pressure from starving families across the country forced Congress to reconsider. With large deposits of grain already wasting away in government possession, the only political move left was to begin a process of donations to the hungry from the Farm Board, a federal oversight created in 1929 to promote the sale and stabilization of agricultural products. Instead of hunger being a reason for the allocation of large grain surpluses, waste became the eventual driving force.

- ^ a b c James Vernon (2007). "Chpts. 1-3". Hunger: A Modern History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02678-0.

- ^ a b c d e f

David Grigg (1981). "The historiography of hunger: changing views on the world food problem 1945–1980". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. NS. 6 (3): 279–292. Bibcode:1981TrIBG...6..279G. doi:10.2307/622288. JSTOR 622288. PMID 12265450.

Before 1945 very little academic or political notice was taken of the problem of world hunger, since 1945 there has been a vast literature on the subject.

- ^ Charles Creighton (2010) [1891]. "Chapt. 1". History of Epidemics in Britain. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-144-94760-4.

- ^ Janet Poppendieck (1995). Eating Agendas. Aldine Transaction. ISBN 978-0-202-30508-0.

- ^ a b c d e John R. Butterly and Jack Shepherd (2006). Hunger: The Biology and Politics of Starvation. Dartmouth College. ISBN 978-1-58465-926-6.

- ^ a b c UK 'aid' is financing a corporate scramble for Africa Archived 12 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Miriam Ross, The Ecologist, 2014.04.03

- ^ a b Fred Magdoff, Twenty-First-Century Land Grabs - Accumulation by Agricultural Dispossession Archived 11 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Monthly Review, 2013, Volume 65, Issue 06 (November)

- ^ a b Rahul Goswami, For Whom Do the FAO and Its Director-General Work? Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Monthly Review Magazine, 2012.12.04

- ^ a b c "Food Price Volatility a Growing Concern, World Bank Stands Ready to Respond". World Bank. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Joseph Stiglitz (7 May 2011). "The IMF's change of heart". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ Caroline Thomas and Tony Evans (2010). ""Poverty, development and hunger"". In John Baylis, Steve Smith and Patricia Owens (ed.). The Globalization of World Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956909-0.

- ^ a b c Javier Blas (18 June 2012). "Food prices: Leaders seek a long-term solution to hunger pains". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ a b Andrew Bowman (27 July 2012). "Food crisis: how do the Brics fare?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Guy Dinmore in L'Aquila (10 July 2009). "G8 to commit $20bn for food security". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ Guy Dinmore in Rome (7 July 2009). "Pope condemns capitalism's 'failures'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ a b c Joanna Rea (25 May 2012). "2012 G8 summit – private sector to the rescue of the world's poorest?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ FAO Food Price Index Archived 30 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Retrieved 4 December 2012

- ^ "Outcome - Copenhagen Consensus Center". www.copenhagenconsensus.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ G8 Action on Food Security and Nutrition Archived 18 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine 2012 statement hosted by the US Department of State

- ^ "Remarks by President concerning the launch of the new alliance for food security and nutrition". 18 May 2012. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Janet Poppendieck (1999). "Introduction, Chpt 1". Sweet Charity?: Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement. Penguine. ISBN 0-14-024556-1.

- ^ David Model (30 October 2012). "Britain's hidden hunger". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "A million hungry children in the UK". Yahoo!. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Charlie Cooper (6 April 2012). "Look back in hunger: Britain's silent, scandalous epidemic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Rowenna Davis (12 May 2012). "The rise and rise of the food bank". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "HOUSEHOLD FOOD SECURITY IN THE GLOBAL NORTH: CHALLENGES AND RESPONSIBILITIES REPORT OF WARWICK CONFERENCE" (PDF). Warwick University. 6 July 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Gregory Meyer (30 July 2012). "US drought: Stuck on dry land: Heatwave threatens new global food crisis". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Javier Bains (12 August 2012). "G20 plans response to rising food prices". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Gregory Meyer in New York and Samantha Pearson in São Paulo (13 August 2013). "Bumper grain crop to weigh on prices". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Gregory Meyer (23 September 2014). "Commodities: Cereal excess". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Michael D. Higgins (15 April 2013). 20130415 Hunger • Nutrition • Climate Justice - Michael D Higgins Speech. EU. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Africa: Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) Leads Transformation of Global Nutrition Agenda with $787 million Investment". AllAfrica. 8 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Luke Cross (8 June 2013). "Hunger Summit secures £2.7bn as thousands rally at Hyde Park". Metro. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona; McVeigh, Karen (11 September 2018). "Global hunger levels rising due to extreme weather, UN warns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ Smitha Mundasad (11 September 2018). "Global hunger increasing, UN warns". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief. Rome: FAO. 2019. pp. 15–16. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (9 April 2020). "Coronavirus could double number of people going hungry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Abdi Latif Dahir (22 April 2020). "'Instead of Coronavirus, the Hunger Will Kill Us.' A Global Food Crisis Looms". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Debora Patta; Haley Ott (2 May 2020). ""I'm starving now": World faces unprecdented hunger crisis amid coronavirus pandemic". CBS News. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023. FAO. 29 November 2023. doi:10.4060/cc8166en. ISBN 978-92-5-138262-2.

- ^ Simon Tisdall (21 May 2022). "Apocalypse now? The alarming effects of the global food crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Organizing for action" (PDF). FAO. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ "Hunger and food security - United Nations Sustainable Development". Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Pope Francis denounces 'global scandal' of hunger". 9 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Leadership Council". www.compact2025.org. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Compact2025: Ending hunger and undernutrition - IFPRI". www.ifpri.org. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Fan, Shenggen and Polman, Paul. 2014. An ambitious development goal: Ending hunger and undernutrition by 2025 Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. In 2013 Global food policy report. Eds. Marble, Andrew and Fritschel, Heidi. Chapter 2. pp. 15–28. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- ^ European Commission Press release. June 2015. EU launches new partnership to combat Undernutrition with Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Archived 26 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 1 November 2015

- ^ sdg indicators, end hunger. "Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture". Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "101 Global Food Organizations to Watch in 2015". Food Tank. January 2015. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ FAO. 2015. Africa's Renewed Partnership to End Hunger by 2025 Archived 28 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 1 November 2015.

- ^ "7 Top Hunger Organizations". Food & Nutrition Magazine. 26 August 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ Riches, G. (1986). Food Banks and the Welfare Crisis. James Lorimer Limited, Publishers. pp. 25, passim, see esp. "Models of Food Banks". ISBN 978-0-88810-363-5. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "The hunger project, overview for Malawi". Thp.org. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Fieldhouse, Paul (2017). Food, Feasts, and Faith: An Encyclopedia of Food Culture in World Religions. ABC-CLIO. pp. 97–102. ISBN 978-1-61069-411-7.

- ^ "From the temple to the street: how Sikh kitchens are becoming the new food banks". The Conversation. 22 July 2015. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Miriam Ross (8 March 2012). "555 million women go hungry worldwide". World Development Movement. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "Mums missing meals to feed kids". The Daily Telegraph. 16 February 2012. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Rabbitt, Matthew P.; Hales, Laura J.; Burke, Michael P.; Coleman-Jensen, Alisha (2023). "Household food security in the United States in 2022". search.nal.usda.gov. doi:10.32747/2023.8134351.ers. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Silva, Andres; Astorga, Andres; Faundez, Rodrigo; Santos, Karla (15 August 2023). "Revisiting food insecurity gender disparity". PLOS ONE. 18 (8): e0287593. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1887593S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287593. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 10426994. PMID 37582082.

- ^ "Who Experiences Hunger". Bread for the World. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "The National Council on Aging". Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "The Facts Behind Senior Hunger - Updated for 2021". 12 November 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "The National Council on Aging". Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Michelle Jurkovich. 2020. Feeding the Hungry: Advocacy and Blame in the Global Fight against Hunger. Cornell University Press.

- Wallerstein, Mitchel B. (1980). Food for War/Food for Peace: U.S. Food Aid in a Global Context. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262231060.

External links

[edit]- Action Against Hunger | ACF-USA

- Action Against Hunger | ACF-UK

- Hunger Relief International | HRI

- Hunger Relief research on IssueLab

- The Global Forum on Food Security and Nutrition (FSN Forum)

- Ten Things you can do to Fight World Hunger Archived 6 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Nation, 13 May 2009

- United Nation 2007 report

- World Food Programme | WFP