Zeno's paradoxes

Zeno's paradoxes are a series of philosophical arguments presented by the ancient Greek philosopher Zeno of Elea (c. 490–430 BC),[1][2] primarily known through the works of Plato, Aristotle, and later commentators like Simplicius of Cilicia.[2] Zeno devised these paradoxes to support his teacher Parmenides's philosophy of monism, which posits that despite our sensory experiences, reality is singular and unchanging. The paradoxes famously challenge the notions of plurality (the existence of many things), motion, space, and time by suggesting they lead to logical contradictions.

Zeno's work, primarily known from second-hand accounts since his original texts are lost, comprises forty "paradoxes of plurality," which argue against the coherence of believing in multiple existences, and several arguments against motion and change.[2] Of these, only a few are definitively known today, including the renowned "Achilles Paradox", which illustrates the problematic concept of infinite divisibility in space and time.[1][2] In this paradox, Zeno argues that a swift runner like Achilles cannot overtake a slower moving tortoise with a head start, because the distance between them can be infinitely subdivided, implying Achilles would require an infinite number of steps to catch the tortoise.[1][2]

These paradoxes have stirred extensive philosophical and mathematical discussion throughout history,[1][2] particularly regarding the nature of infinity and the continuity of space and time. Initially, Aristotle's interpretation, suggesting a potential rather than actual infinity, was widely accepted.[1] However, modern solutions leveraging the mathematical framework of calculus have provided a different perspective, highlighting Zeno's significant early insight into the complexities of infinity and continuous motion.[1] Zeno's paradoxes remain a pivotal reference point in the philosophical and mathematical exploration of reality, motion, and the infinite, influencing both ancient thought and modern scientific understanding.[1][2]

History

[edit]The origins of the paradoxes are somewhat unclear, but they are generally thought to have been developed to support Parmenides' doctrine of monism, that all of reality is one, and that all change is impossible, that is, that nothing ever changes in location or in any other respect.[1][2] Diogenes Laërtius, citing Favorinus, says that Zeno's teacher Parmenides was the first to introduce the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise. But in a later passage, Laërtius attributes the origin of the paradox to Zeno, explaining that Favorinus disagrees.[3] Modern academics attribute the paradox to Zeno.[1][2]

Many of these paradoxes argue that contrary to the evidence of one's senses, motion is nothing but an illusion.[1][2] In Plato's Parmenides (128a–d), Zeno is characterized as taking on the project of creating these paradoxes because other philosophers claimed paradoxes arise when considering Parmenides' view. Zeno's arguments may then be early examples of a method of proof called reductio ad absurdum, also known as proof by contradiction. Thus Plato has Zeno say the purpose of the paradoxes "is to show that their hypothesis that existences are many, if properly followed up, leads to still more absurd results than the hypothesis that they are one."[4] Plato has Socrates claim that Zeno and Parmenides were essentially arguing exactly the same point.[5] They are also credited as a source of the dialectic method used by Socrates.[6]

Paradoxes

[edit]Some of Zeno's nine surviving paradoxes (preserved in Aristotle's Physics[7][8] and Simplicius's commentary thereon) are essentially equivalent to one another. Aristotle offered a response to some of them.[7] Popular literature often misrepresents Zeno's arguments. For example, Zeno is often said to have argued that the sum of an infinite number of terms must itself be infinite–with the result that not only the time, but also the distance to be travelled, become infinite.[9] However, none of the original ancient sources has Zeno discussing the sum of any infinite series. Simplicius has Zeno saying "it is impossible to traverse an infinite number of things in a finite time". This presents Zeno's problem not with finding the sum, but rather with finishing a task with an infinite number of steps: how can one ever get from A to B, if an infinite number of (non-instantaneous) events can be identified that need to precede the arrival at B, and one cannot reach even the beginning of a "last event"?[10][11][12][13]

Paradoxes of motion

[edit]Three of the strongest and most famous—that of Achilles and the tortoise, the Dichotomy argument, and that of an arrow in flight—are presented in detail below.

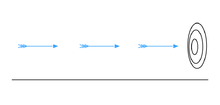

Dichotomy paradox

[edit]

That which is in locomotion must arrive at the half-way stage before it arrives at the goal.

Suppose Atalanta wishes to walk to the end of a path. Before she can get there, she must get halfway there. Before she can get halfway there, she must get a quarter of the way there. Before traveling a quarter, she must travel one-eighth; before an eighth, one-sixteenth; and so on.

The resulting sequence can be represented as:

This description requires one to complete an infinite number of tasks, which Zeno maintains is an impossibility.[14]

This sequence also presents a second problem in that it contains no first distance to run, for any possible (finite) first distance could be divided in half, and hence would not be first after all. Hence, the trip cannot even begin. The paradoxical conclusion then would be that travel over any finite distance can be neither completed nor begun, and so all motion must be an illusion.[15]

This argument is called the "Dichotomy" because it involves repeatedly splitting a distance into two parts. An example with the original sense can be found in an asymptote. It is also known as the Race Course paradox.

Achilles and the tortoise

[edit]

In a race, the quickest runner can never overtake the slowest, since the pursuer must first reach the point whence the pursued started, so that the slower must always hold a lead.

In the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise, Achilles is in a footrace with a tortoise. Achilles allows the tortoise a head start of 100 meters, for example. Suppose that each racer starts running at some constant speed, one faster than the other. After some finite time, Achilles will have run 100 meters, bringing him to the tortoise's starting point. During this time, the tortoise has run a much shorter distance, say 2 meters. It will then take Achilles some further time to run that distance, by which time the tortoise will have advanced farther; and then more time still to reach this third point, while the tortoise moves ahead. Thus, whenever Achilles arrives somewhere the tortoise has been, he still has some distance to go before he can even reach the tortoise. As Aristotle noted, this argument is similar to the Dichotomy.[16] It lacks, however, the apparent conclusion of motionlessness.

Arrow paradox

[edit]

If everything when it occupies an equal space is at rest at that instant of time, and if that which is in locomotion is always occupying such a space at any moment, the flying arrow is therefore motionless at that instant of time and at the next instant of time but if both instants of time are taken as the same instant or continuous instant of time then it is in motion.[17]

In the arrow paradox, Zeno states that for motion to occur, an object must change the position which it occupies. He gives an example of an arrow in flight. He states that at any one (durationless) instant of time, the arrow is neither moving to where it is, nor to where it is not.[18] It cannot move to where it is not, because no time elapses for it to move there; it cannot move to where it is, because it is already there. In other words, at every instant of time there is no motion occurring. If everything is motionless at every instant, and time is entirely composed of instants, then motion is impossible.

Whereas the first two paradoxes divide space, this paradox starts by dividing time—and not into segments, but into points.[19]

Other paradoxes

[edit]Aristotle gives three other paradoxes.

Paradox of place

[edit]From Aristotle:

If everything that exists has a place, place too will have a place, and so on ad infinitum.[20]

Paradox of the grain of millet

[edit]Description of the paradox from the Routledge Dictionary of Philosophy:

The argument is that a single grain of millet makes no sound upon falling, but a thousand grains make a sound. Hence a thousand nothings become something, an absurd conclusion.[21]

Aristotle's response:

Zeno's reasoning is false when he argues that there is no part of the millet that does not make a sound: for there is no reason why any such part should not in any length of time fail to move the air that the whole bushel moves in falling. In fact it does not of itself move even such a quantity of the air as it would move if this part were by itself: for no part even exists otherwise than potentially.[22]

Description from Nick Huggett:

This is a Parmenidean argument that one cannot trust one's sense of hearing. Aristotle's response seems to be that even inaudible sounds can add to an audible sound.[23]

The moving rows (or stadium)

[edit]

From Aristotle:

... concerning the two rows of bodies, each row being composed of an equal number of bodies of equal size, passing each other on a race-course as they proceed with equal velocity in opposite directions, the one row originally occupying the space between the goal and the middle point of the course and the other that between the middle point and the starting-post. This...involves the conclusion that half a given time is equal to double that time.[24]

An expanded account of Zeno's arguments, as presented by Aristotle, is given in Simplicius's commentary On Aristotle's Physics.[25][2][1]

According to Angie Hobbs of Sheffield university, this paradox is intended to be considered together with the paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise, problematizing the concept of discrete space & time where the other problematizes the concept of infinitely divisible space & time.[26]

Proposed solutions

[edit]In classical antiquity

[edit]According to Simplicius, Diogenes the Cynic said nothing upon hearing Zeno's arguments, but stood up and walked, in order to demonstrate the falsity of Zeno's conclusions.[25][2] To fully solve any of the paradoxes, however, one needs to show what is wrong with the argument, not just the conclusions. Throughout history several solutions have been proposed, among the earliest recorded being those of Aristotle and Archimedes.

Aristotle (384 BC–322 BC) remarked that as the distance decreases, the time needed to cover those distances also decreases, so that the time needed also becomes increasingly small.[27][failed verification][28] Aristotle also distinguished "things infinite in respect of divisibility" (such as a unit of space that can be mentally divided into ever smaller units while remaining spatially the same) from things (or distances) that are infinite in extension ("with respect to their extremities").[29] Aristotle's objection to the arrow paradox was that "Time is not composed of indivisible nows any more than any other magnitude is composed of indivisibles."[30] Thomas Aquinas, commenting on Aristotle's objection, wrote "Instants are not parts of time, for time is not made up of instants any more than a magnitude is made of points, as we have already proved. Hence it does not follow that a thing is not in motion in a given time, just because it is not in motion in any instant of that time."[31][32][33]

In modern mathematics

[edit]Some mathematicians and historians, such as Carl Boyer, hold that Zeno's paradoxes are simply mathematical problems, for which modern calculus provides a mathematical solution.[34] Infinite processes remained theoretically troublesome in mathematics until the late 19th century. With the epsilon-delta definition of limit, Weierstrass and Cauchy developed a rigorous formulation of the logic and calculus involved. These works resolved the mathematics involving infinite processes.[35][36]

Some philosophers, however, say that Zeno's paradoxes and their variations (see Thomson's lamp) remain relevant metaphysical problems.[10][11][12] While mathematics can calculate where and when the moving Achilles will overtake the Tortoise of Zeno's paradox, philosophers such as Kevin Brown[10] and Francis Moorcroft[11] hold that mathematics does not address the central point in Zeno's argument, and that solving the mathematical issues does not solve every issue the paradoxes raise. Brown concludes "Given the history of 'final resolutions', from Aristotle onwards, it's probably foolhardy to think we've reached the end. It may be that Zeno's arguments on motion, because of their simplicity and universality, will always serve as a kind of 'Rorschach image' onto which people can project their most fundamental phenomenological concerns (if they have any)."[10]

Henri Bergson

[edit]An alternative conclusion, proposed by Henri Bergson in his 1896 book Matter and Memory, is that, while the path is divisible, the motion is not.[37][38]

Peter Lynds

[edit]In 2003, Peter Lynds argued that all of Zeno's motion paradoxes are resolved by the conclusion that instants in time and instantaneous magnitudes do not physically exist.[39][40][41] Lynds argues that an object in relative motion cannot have an instantaneous or determined relative position (for if it did, it could not be in motion), and so cannot have its motion fractionally dissected as if it does, as is assumed by the paradoxes. Nick Huggett argues that Zeno is assuming the conclusion when he says that objects that occupy the same space as they do at rest must be at rest.[19]

Bertrand Russell

[edit]Based on the work of Georg Cantor,[42] Bertrand Russell offered a solution to the paradoxes, what is known as the "at-at theory of motion". It agrees that there can be no motion "during" a durationless instant, and contends that all that is required for motion is that the arrow be at one point at one time, at another point another time, and at appropriate points between those two points for intervening times. In this view motion is just change in position over time.[43][44]

Hermann Weyl

[edit]Another proposed solution is to question one of the assumptions Zeno used in his paradoxes (particularly the Dichotomy), which is that between any two different points in space (or time), there is always another point. Without this assumption there are only a finite number of distances between two points, hence there is no infinite sequence of movements, and the paradox is resolved. According to Hermann Weyl, the assumption that space is made of finite and discrete units is subject to a further problem, given by the "tile argument" or "distance function problem".[45][46] According to this, the length of the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle in discretized space is always equal to the length of one of the two sides, in contradiction to geometry. Jean Paul Van Bendegem has argued that the Tile Argument can be resolved, and that discretization can therefore remove the paradox.[34][47]

Applications

[edit]Quantum Zeno effect

[edit]In 1977,[48] physicists E. C. George Sudarshan and B. Misra discovered that the dynamical evolution (motion) of a quantum system can be hindered (or even inhibited) through observation of the system.[49] This effect is usually called the "Quantum Zeno effect" as it is strongly reminiscent of Zeno's arrow paradox. This effect was first theorized in 1958.[50]

Zeno behaviour

[edit]In the field of verification and design of timed and hybrid systems, the system behaviour is called Zeno if it includes an infinite number of discrete steps in a finite amount of time.[51] Some formal verification techniques exclude these behaviours from analysis, if they are not equivalent to non-Zeno behaviour.[52][53] In systems design these behaviours will also often be excluded from system models, since they cannot be implemented with a digital controller.[54]

Similar paradoxes

[edit]School of Names

[edit]

Roughly contemporaneously during the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), ancient Chinese philosophers from the School of Names, a school of thought similarly concerned with logic and dialectics, developed paradoxes similar to those of Zeno. The works of the School of Names have largely been lost, with the exception of portions of the Gongsun Longzi. The second of the Ten Theses of Hui Shi suggests knowledge of infinitesimals:That which has no thickness cannot be piled up; yet it is a thousand li in dimension. Among the many puzzles of his recorded in the Zhuangzi is one very similar to Zeno's Dichotomy:

"If from a stick a foot long you every day take the half of it, in a myriad ages it will not be exhausted."

— Zhuangzi, chapter 33 (Legge translation)[55]

The Mohist canon appears to propose a solution to this paradox by arguing that in moving across a measured length, the distance is not covered in successive fractions of the length, but in one stage. Due to the lack of surviving works from the School of Names, most of the other paradoxes listed are difficult to interpret.[56]

Lewis Carroll's "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles"

[edit]"What the Tortoise Said to Achilles",[57] written in 1895 by Lewis Carroll, describes a paradoxical infinite regress argument in the realm of pure logic. It uses Achilles and the Tortoise as characters in a clear reference to Zeno's paradox of Achilles.[58]

See also

[edit]- Incommensurable magnitudes

- Infinite regress

- Philosophy of space and time

- Renormalization

- Ross–Littlewood paradox

- Supertask

- Zeno machine

- List of paradoxes

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Zeno's Paradoxes | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Huggett, Nick (2024), "Zeno's Paradoxes", in Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2024 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2024-03-25

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives, 9.23 and 9.29.

- ^ Parmenides 128d

- ^ Parmenides 128a–b

- ^ ([fragment 65], Diogenes Laërtius. IX Archived 2010-12-12 at the Wayback Machine 25ff and VIII 57).

- ^ a b Aristotle's Physics Archived 2011-01-06 at the Wayback Machine "Physics" by Aristotle translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye

- ^ "Greek text of "Physics" by Aristotle (refer to §4 at the top of the visible screen area)". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16.

- ^ Benson, Donald C. (1999). The Moment of Proof : Mathematical Epiphanies. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0195117219.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Kevin. "Zeno and the Paradox of Motion". Reflections on Relativity. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ a b c Moorcroft, Francis. "Zeno's Paradox". Archived from the original on 2010-04-18.

- ^ a b Papa-Grimaldi, Alba (1996). "Why Mathematical Solutions of Zeno's Paradoxes Miss the Point: Zeno's One and Many Relation and Parmenides' Prohibition" (PDF). The Review of Metaphysics. 50: 299–314. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-06-09. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ^ Huggett, Nick (2010). "Zeno's Paradoxes: 5. Zeno's Influence on Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ Lindberg, David (2007). The Beginnings of Western Science (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Huggett, Nick (2010). "Zeno's Paradoxes: 3.1 The Dichotomy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ Huggett, Nick (2010). "Zeno's Paradoxes: 3.2 Achilles and the Tortoise". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ Aristotle. "Physics". The Internet Classics Archive. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

Zeno's reasoning, however, is fallacious, when he says that if everything when it occupies an equal space is at rest, and if that which is in locomotion is always occupying such a space at any moment, the flying arrow is therefore motionless. This is false, for time is not composed of indivisible moments any more than any other magnitude is composed of indivisibles.

- ^ Laërtius, Diogenes (c. 230). "Pyrrho". Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Vol. IX. passage 72. ISBN 1-116-71900-2. Archived from the original on 2011-08-22. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ a b Huggett, Nick (2010). "Zeno's Paradoxes: 3.3 The Arrow". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ Aristotle Physics IV:1, 209a25 Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Michael Proudfoot, A.R. Lace. Routledge Dictionary of Philosophy. Routledge 2009, p. 445

- ^ Aristotle Physics VII:5, 250a20 Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huggett, Nick, "Zeno's Paradoxes", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/paradox-zeno/#GraMil Archived 2022-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aristotle Physics VI:9, 239b33 Archived 2008-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Simplikios; Konstan, David; Simplikios (1989). Simplicius on Aristotle's Physics 6. Ancient commentators on Aristotle. Ithaca N.Y: Cornell Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0-8014-2238-6.

- ^ "Zeno's Paradoxes: The Moving Rows". The University of Sheffield Kaltura Digital Media Hub. Retrieved 2024-06-28.

- ^ Aristotle. Physics 6.9

- ^ Aristotle's observation that the fractional times also get shorter does not guarantee, in every case, that the task can be completed. One case in which it does not hold is that in which the fractional times decrease in a harmonic series, while the distances decrease geometrically, such as: 1/2 s for 1/2 m gain, 1/3 s for next 1/4 m gain, 1/4 s for next 1/8 m gain, 1/5 s for next 1/16 m gain, 1/6 s for next 1/32 m gain, etc. In this case, the distances form a convergent series, but the times form a divergent series, the sum of which has no limit. [original research?] Archimedes developed a more explicitly mathematical approach than Aristotle.

- ^ Aristotle. Physics 6.9; 6.2, 233a21-31

- ^ Aristotle. Physics. Vol. VI. Part 9 verse: 239b5. ISBN 0-585-09205-2. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ Aquinas. Commentary on Aristotle's Physics, Book 6.861

- ^ Kiritsis, Paul (2020-04-01). A Critical Investigation into Precognitive Dreams (1 ed.). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-1527546332.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Aquinas, Thomas. "Commentary on Aristotle's Physics". aquinas.cc. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ a b Boyer, Carl (1959). The History of the Calculus and Its Conceptual Development. Dover Publications. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-486-60509-8. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

If the paradoxes are thus stated in the precise mathematical terminology of continuous variables (...) the seeming contradictions resolve themselves.

- ^ Lee, Harold (1965). "Are Zeno's Paradoxes Based on a Mistake?". Mind. 74 (296). Oxford University Press: 563–570. doi:10.1093/mind/LXXIV.296.563. JSTOR 2251675.

- ^ B Russell (1956) Mathematics and the metaphysicians in "The World of Mathematics" (ed. J R Newman), pp 1576-1590.

- ^ Bergson, Henri (1896). Matière et Mémoire [Matter and Memory] (PDF). Translation 1911 by Nancy Margaret Paul & W. Scott Palmer. George Allen and Unwin. pp. 77–78 of the PDF. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- ^ Massumi, Brian (2002). Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (1st ed.). Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0822328971.

- ^ "Zeno's Paradoxes: A Timely Solution". January 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-08-13. Retrieved 2012-07-02.

- ^ Lynds, Peter. Time and Classical and Quantum Mechanics: Indeterminacy vs. Discontinuity. Foundations of Physics Letter s (Vol. 16, Issue 4, 2003). doi:10.1023/A:1025361725408

- ^ Time’s Up, Einstein Archived 2012-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, Josh McHugh, Wired Magazine, June 2005

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2002) [First published in 1914 by The Open Court Publishing Company]. "Lecture 6. The Problem of Infinity Considered Historically". Our Knowledge of the External World: As a Field for Scientific Method in Philosophy. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 0-415-09605-7.

- ^ Huggett, Nick (1999). Space From Zeno to Einstein. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-08271-3.

- ^ Salmon, Wesley C. (1998). Causality and Explanation. Oxford University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-19-510864-4. Archived from the original on 2023-12-29. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Van Bendegem, Jean Paul (17 March 2010). "Finitism in Geometry". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ Cohen, Marc (11 December 2000). "ATOMISM". History of Ancient Philosophy, University of Washington. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ van Bendegem, Jean Paul (1987). "Discussion:Zeno's Paradoxes and the Tile Argument". Philosophy of Science. 54 (2). Belgium: 295–302. doi:10.1086/289379. JSTOR 187807. S2CID 224840314.

- ^ Sudarshan, E. C. G.; Misra, B. (1977). "The Zeno's paradox in quantum theory" (PDF). Journal of Mathematical Physics. 18 (4): 756–763. Bibcode:1977JMP....18..756M. doi:10.1063/1.523304. OSTI 7342282. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ^ W.M.Itano; D.J. Heinsen; J.J. Bokkinger; D.J. Wineland (1990). "Quantum Zeno effect" (PDF). Physical Review A. 41 (5): 2295–2300. Bibcode:1990PhRvA..41.2295I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.41.2295. PMID 9903355. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-07-20. Retrieved 2004-07-23.

- ^ Khalfin, L.A. (1958). "Contribution to the Decay Theory of a Quasi-Stationary State". Soviet Phys. JETP. 6: 1053. Bibcode:1958JETP....6.1053K.

- ^ Paul A. Fishwick, ed. (1 June 2007). "15.6 "Pathological Behavior Classes" in chapter 15 "Hybrid Dynamic Systems: Modeling and Execution" by Pieter J. Mosterman, The Mathworks, Inc.". Handbook of dynamic system modeling. Chapman & Hall/CRC Computer and Information Science (hardcover ed.). Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press. pp. 15–22 to 15–23. ISBN 978-1-58488-565-8. Archived from the original on 2023-12-29. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ Lamport, Leslie (2002). "Specifying Systems" (PDF). Microsoft Research. Addison-Wesley: 128. ISBN 0-321-14306-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-11-16. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ Zhang, Jun; Johansson, Karl; Lygeros, John; Sastry, Shankar (2001). "Zeno hybrid systems" (PDF). International Journal for Robust and Nonlinear Control. 11 (5): 435. doi:10.1002/rnc.592. S2CID 2057416. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2011. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Franck, Cassez; Henzinger, Thomas; Raskin, Jean-Francois (2002). A Comparison of Control Problems for Timed and Hybrid Systems. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Müller, Max, ed. (1891). "The Writings of Kwang Tse". Sacred Books of the East. Vol. 40. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "School of Names > Miscellaneous Paradoxes (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". plato.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (1895-04-01). "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles". Mind. IV (14): 278–280. doi:10.1093/mind/IV.14.278. ISSN 0026-4423. Archived from the original on 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- ^ Tsilipakos, Leonidas (2021). Clarity and confusion in social theory: taking concepts seriously. Philosophy and method in the social sciences. Abingdon New York (N.Y.): Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-032-09883-8.

References

[edit]- Kirk, G. S., J. E. Raven, M. Schofield (1984) The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27455-9.

- Huggett, Nick (2010). "Zeno's Paradoxes". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- Plato (1926) Plato: Cratylus. Parmenides. Greater Hippias. Lesser Hippias, H. N. Fowler (Translator), Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 0-674-99185-0.

- Sainsbury, R.M. (2003) Paradoxes, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48347-6.

- Skyrms, Brian (1983). "Zeno's Paradox of Measure". In Cohen, R. S.; Laudan, L. (eds.). Physics, Philosophy, and Psychoanalysis. Dordrecht: Reidel. pp. 223–254. ISBN 90-277-1533-5.

External links

[edit]- Dowden, Bradley. "Zeno’s Paradoxes." Entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Antinomy", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

- Silagadze, Z. K. "Zeno meets modern science,"

- Zeno's Paradox: Achilles and the Tortoise by Jon McLoone, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Kevin Brown on Zeno and the Paradox of Motion

- Palmer, John (2008). "Zeno of Elea". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- This article incorporates material from Zeno's paradox on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

- Grime, James. "Zeno's Paradox". Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2013-04-13.