Bella Abzug

Bella Abzug | |

|---|---|

Abzug in 1978 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York | |

| In office January 3, 1971 – January 3, 1977 | |

| Preceded by | Leonard Farbstein |

| Succeeded by | Ted Weiss |

| Constituency | 19th district (1971–1973) 20th district (1973–1977) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Bella Savitsky July 24, 1920 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 31, 1998 (aged 77) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Martin Abzug

(m. 1944; died 1986) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Arlene Stringer-Cuevas (cousin) Scott Stringer (cousin) |

| Education | Hunter College (BA) Columbia University (LLB) Jewish Theological Seminary |

Bella Abzug (née Savitzky; July 24, 1920 – March 31, 1998), nicknamed "Battling Bella", was an American lawyer, politician, social activist, and a leader in the women's movement. In 1971, Abzug joined other leading feminists such as Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and Betty Friedan to found the National Women's Political Caucus.[1] She was a leading figure in what came to be known as ecofeminism.[2]

In 1970, Abzug's first campaign slogan was, "This woman's place is in the House—the House of Representatives."[3] She was later appointed to co-chair the National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year created by President Gerald Ford's executive order, presided over the 1977 National Women's Conference, and led President Jimmy Carter's National Advisory Commission for Women.[4] Abzug was a founder of the Commission for Women's Equality of the American Jewish Congress.[5]

Early life

[edit]Bella Savitzky was born on July 24, 1920, in New York City.[6] Both of her parents were Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Chernihiv, Russian Empire (now Ukraine).[7][8][9] Her mother, Esther (née Tanklevsky or Tanklefsky), was a homemaker who immigrated from Kozelets in 1902.[7] Her father, Emanuel Savitzky, was a butcher who emigrated in 1906.[6] He ran the Live and Let Live Meat Market on Ninth Avenue.[10] Even in her youth, she was competitive and would beat other children in all sorts of competitions.[11][12] She ran the cash register at her father's deli as a young girl.[10]

Her religious upbringing influenced her development into a feminist. According to Abzug, "It was during these visits to the synagogue that I think I had my first thoughts as a feminist rebel. I didn't like the fact that women were consigned to the back rows of the balcony."[13] When her father died, Abzug, then 13, was told that her Orthodox synagogue did not permit women to say the (mourners') Kaddish, since that rite was reserved for sons of the deceased. However, because her father had no sons, she went to the synagogue every morning for a year to recite the prayer, defying the tradition of her congregation's practice of Orthodox Judaism.[5][14]

Abzug graduated from Walton High School in The Bronx, where she was class president.[9] Through high school she took violin lessons and went to Florence Marshall Hebrew High School after classes at Walton.[11] She went on to major in political science at Hunter College of the City University of New York and simultaneously attended the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. At Hunter College, she was student council president and active in the American Student Union. Abzug first met Mim Kelber, who would go on to co-found WEDO with her, at Walton High School and they went on to attend Hunter College with one another. She later earned a law degree from Columbia University in 1944.[6]

Legal and political career

[edit]Abzug was admitted to the New York Bar in 1945, at a time when very few women practiced law, and started her career in New York City at the firm of Pressman, Witt & Cammer, frequently working cases in matters of labor law.

As a lawyer, she specialized in labor rights, tenants' rights, and civil liberties cases.[15] Early on, she took on civil rights cases in the Southern United States. She appealed the case of Willie McGee, a black man convicted in 1945 of raping a white woman in Laurel, Mississippi, and sentenced to death by an all-white jury who deliberated for only two-and-a-half minutes. Abzug lost the appeal and the man was executed.[16] Abzug was an outspoken advocate of liberal causes, including the Equal Rights Amendment, and opposition to the Vietnam War as well as the military draft.[6][17] She worked for the American Civil Liberties Union and the Civil Rights Congress.[5]

Years before she was elected to the House of Representatives, she was an early participant in Women Strike for Peace.[6][15][18] Her political stance placed her on the master list of Nixon's political opponents.[citation needed] During the McCarthy era, she was one of the few legal attorneys willing to openly combat the House Un-American Activities Committee.[15][5]

Congressional career

[edit]I've been described as a tough and noisy woman, a prizefighter, a man-hater, you name it. They call me Battling Bella.

— Bella Abzug, in her 1971 Congress journal, quoted by Braden in Women Politicians and the Media[19]

Elections

[edit]Nicknamed "Battling Bella",[19][17] in 1970 she challenged the 14-year incumbent Leonard Farbstein in the Democratic primary for a congressional district on Manhattan's West Side. She defeated Farbstein in a considerable upset and then defeated talk show host Barry Farber in the general election. In 1972, her district was eliminated via redistricting and she chose to run against William Fitts Ryan, who also represented part of the West Side, in the Democratic primary. Ryan, although seriously ill, defeated Abzug. However, Ryan died before the general election and Abzug defeated his widow, Priscilla, at the party's convention to choose the new Democratic nominee. In the general election Priscilla Ryan challenged Abzug on the Liberal Party line, but was unsuccessful.[20] She was reelected easily in 1974. For her last two terms, she represented part of the Bronx as well.

Tenure

[edit]

She was one of the first members of Congress to support gay rights, introducing the first federal gay rights bill, known as the Equality Act of 1974, with fellow Democratic New York City representative Ed Koch, who later became mayor of New York.[21][17] She also chaired historic hearings on government secrecy, being the chair for the Subcommittee on Government Information and Individual Rights. She was voted by her colleagues as the third most influential member of the House as reported in U.S. News & World Report.

She was the sponsor for the Equality Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) that made it unlawful to discriminate against any applicant, with respect to any aspect of a credit transaction, on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, or age.[22]

She was frequently verbally abusive toward staff members, including referring to Doug Ireland as a "fat cocksucker."[23]

Although they were banned on the House floor, Abzug was known for her colorful and vibrant hats and was seldom seen without one. After being forced to remove her iconic hat before entering the House floor, Abzug once remarked that she felt "naked and unrecognizable." She famously reminded all who admired them: "It's what's under the hat that counts!"[24][17]

In February 1975, Abzug was part of a bipartisan delegation sent to Saigon by President Gerald Ford to assess the situation on the ground in South Vietnam near the end of the Vietnam War.[25]

Abzug was a supporter of Zionism. As a young woman she was a member of the Socialist-Zionist youth movement of Hashomer Hatzair.[26] In 1975, she challenged the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 (revoked in 1991 by resolution 46/86), which "determine[d] that Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination."[27] Abzug said about the topic, "Zionism is a liberation movement."[5]

Campaign for U.S. Senate

[edit]Abzug's career in Congress ended with an unsuccessful bid for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate in 1976, which she lost by less than one percent to the more moderate Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who had served in both the Nixon and Ford Republican presidential administrations as White House Urban Affairs Advisor, Counselor to the President, United States Ambassador to India, and United States Ambassador to the United Nations. Moynihan would go on to serve four terms in that office.[6][28]

Later life and death

[edit]

Abzug never held elected office again after leaving the House, although she remained a high-profile figure and was again a candidate on multiple occasions. She was unsuccessful in her bid to be mayor of New York City in 1977,[29] as well as in attempts to return to the US House from the East Side of Manhattan in 1978 against Republican Bill Green,[30] and from Westchester County, New York, in 1986 against Joe DioGuardi.[31]

She authored two books, Bella: Ms. Abzug Goes to Washington[32] and The Gender Gap,[33] the latter co-authored with friend and colleague Mim Kelber.

In early 1977, President Jimmy Carter chose a new National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year and appointed Abzug to head it. Numerous events were held over the next two years, culminating in the 1977 National Women's Conference in November.[34] She would continue this work as one of the two co-chairpersons for the National Advisory Committee for Women until her dismissal in January 1979, which would create a flash point of tension between the Carter administration and feminist organizations in the United States.[35]

Abzug founded and ran several women's advocacy organizations. She founded a grassroots organization called Women USA,[15] and continued to lead feminist advocacy events, for example serving as grand marshal of the Women's Equality Day New York March on August 26, 1980.[36]

In the last decade of her life, in the early 1990s, with Kelber, she co-founded the Women's Environment and Development Organization (WEDO), in their own words "a global women's advocacy organization working towards a just world that promotes and protects human rights, gender equality, and the integrity of the environment."[37] In 1991, WEDO held the World Women's Congress for a Healthy Planet in Miami, where 1,500 women from 83 countries produced the Women's Action Agenda 21.[38]

At the UN, Abzug developed the Women's Caucus, which analyzed documents, proposed gender-sensitive policies and language, and lobbied to advance the Women's Agenda for the 21st Century at the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, as well as women's issues at other events including the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995.[38]

During her last years, Bella kept up her busy schedule of travel and work, even though she traveled in a wheelchair. Bella led WEDO until her death, giving her final public speech before the UN in March 1998.[39]

After battling breast cancer for a number of years, she developed heart disease and died at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center on March 31, 1998, from complications following open heart surgery. She was 77.[40] Abzug was interred at Mount Carmel Cemetery, Glendale, Queens County, New York.[41]

Personal life

[edit]In 1944, Bella married Martin Abzug, a novelist and stockbroker. They met on a bus in Miami, Florida while heading to a Yehudi Menuhin concert, and they remained married until his death in 1986.[42] They had two daughters.

Abzug was a cousin of Arlene Stringer-Cuevas and her son Scott Stringer, who were also involved in politics in New York City.[43]

Abzug used to comment that if male lawmakers were going to swim naked in the Congressional swimming pool as was the tradition, that that would be fine with her.[44][45]

Honors and legacy

[edit]In 1974, Jeff London created a sculptural "People Furniture" of Abzug having a good idea.

In 1991, Abzug received the "Maggie" Award, the highest honor of the Planned Parenthood Federation, in tribute to their founder, Margaret Sanger.[46]

In 1994, Abzug was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls.[6] The same year, she received a medal from the Veteran Feminists of America.[17]

Abzug was honored on March 6, 1997, at the United Nations as a leading female environmentalist.[6] She received the highest civilian recognition and honor at the U.N., the Blue Beret Peacekeepers Award.[47]

In 2004, her daughter Liz Abzug, an adjunct Urban Studies Professor at Barnard College and a political consultant, founded the Bella Abzug Leadership Institute (BALI) to mentor and train high school and college women to become effective leaders in civic, political, corporate and community life. To commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the first National Women's Conference held in Houston in 1977, over which Bella Abzug had presided, BALI hosted a National Women's Conference on the weekend of November 10–11, 2007, at Hunter College (NYC). Over 600 people from around the world attended. Besides celebrating the 1977 Conference, the 2007 agenda was to address significant women's issues for the 21st century.[48]

In 2017, Time magazine named Abzug one of its 50 Women Who Made American Political History.[49]

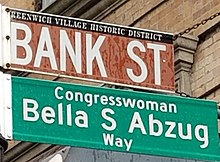

Various landmarks in New York City bear Abzug's name. On March 1, 2019, the recently built Hudson Yards Park was renamed Bella Abzug Park as a tribute to women's history month and its location in her former Congressional district.[50] In New York City's Greenwich Village, a portion of Bank Street is named for Abzug.[51]

In popular culture

[edit]She appeared in the WLIW video A Laugh, A Tear, A Mitzvah,[52] as well as in Woody Allen's Manhattan as herself,[53] a 1977 episode of Saturday Night Live,[54] and the documentary New York: A Documentary Film.[55]

In 1979, the Supersisters trading card set was produced and distributed; one of the cards featured Abzug's name and picture.[56]

Abzug appeared in Shirley MacLaine's autobiographical book Out on a Limb (1983). In the 1987 ABC Television mini-series of the same name, Abzug was played by Anne Jackson.[57]

In 2019 Manhattan Theater Club, in New York City, produced Bella Bella, a one-character show written and performed by Harvey Fierstein. In the show, Fierstein portrayed Abzug and created dialogue "from the words of Bella Abzug."[58]

In the 2020 FX limited series, Mrs. America, Margo Martindale portrays Abzug.[59] The program examines the unsuccessful multi-year battle to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.[59] That same year, Bette Midler portrayed Abzug in the film The Glorias.[60]

Abzug was featured in a segment in the 2007 documentary NY77: The Coolest Year in Hell, which explores in depth what life was like during the year 1977 in Manhattan. An excerpt from a press conference of Bella Abzug is used when discussing the differences in political views between Abzug and fellow mayoral candidate Ed Koch. Geraldo Rivera gave detailed commentary on Bella's personality and political style.[61]

Jeff L. Lieberman produced the 2023 documentary Bella! about Abzug's life and political achievements. The film includes interviews with Barbra Streisand, Shirley MacLaine, Hillary Clinton, Lily Tomlin, Nancy Pelosi, Gloria Steinem, Maxine Waters, Phil Donahue, Marlo Thomas, Charles Rangel, David Dinkins, and Renée Taylor.

Selected bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Abzug, Bella (1972). Ziegler, Mel (ed.). Bella!: Ms. Abzug goes to Washington. New York: Saturday Review Press. ISBN 9780841501546.

- Abzug, Bella; Kelber, Mim (1984). Gender gap: Bella Abzug's guide to political power for American women. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395354841.

- Abzug, Bella (1995). Women: looking beyond 2000. New York, New York: United Nations. ISBN 9789211005929.

- Abzug, Bella; Zarnow, Leandra (2019). Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674737488.

Papers

[edit]- Abzug, Bella; Jain, Devaki (August 1996). Women's leadership and the ethics of development (Gender in Development Monograph Series #4). New York: UNDP United Nations Development Programme. Link.

See also

[edit]- Women's Equality Day

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

- List of Jewish feminists

- List of Jewish members of the United States Congress

References

[edit]- ^ "Bella Abzug". HISTORY. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ Jaffe-Gill, Ellen (1998). "Bella Abzug, No One Could Have Stopped Me". The Jewish Woman's Book of Wisdom. Citadel Press. p. 74. ISBN 1559724803.

- ^ "ABZUG, Bella Savitzky". History, Art, & Archives: US House of Representatives. Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "1977 National Women's Conference: A Question of Choices", 1977-11-21, The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at the University of Georgia, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

- ^ a b c d e Mark, Jonathan (April 3, 1998). "Bella Abzug's Jewish Heart". jewishweek.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kathryn Cullen-DuPont (August 1, 2000). Encyclopedia of women's history in America. Infobase Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8160-4100-8. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ a b All New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820–1957

- ^ 1930 United States census

- ^ a b Barbara J. Love (2006). Feminists who changed America, 1963-1975. University of Illinois Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-252-03189-2. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ a b "PERSONALITY: Bellacose Abzug". Time. August 16, 1971. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Bella Abzug profile". jwa.org. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Levy, Alan Howard. The Political Life of Bella Abzug, 1920–1976 Political Passions, Women's Rights, and Congressional Battles. Lanham, Md.: Lexington, 2013.

- ^ Ziegler, Mel (1972). Bella!: Ms. Abzug Goes to Washington. New York: Saturday Review Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780841501546.

- ^ Jaffe-Gill, Ellen (1998). "Bella Abzug, No One Could Have Stopped Me". The Jewish Woman's Book of Wisdom. Citadel Press. pp. 4, 74. ISBN 1559724803.

- ^ a b c d "Bella Abzug". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ Suzanne Braun Levine and Mary Thom, Bella Abzug: How One Tough Broad from the Bronx Fought Jim Crow and Joe McCarthy, Pissed Off Jimmy Carter, Battled for the Rights of Women and Workers, ... Planet, and Shook Up Politics Along the Way, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007; ISBN 0-374-29952-8, pp. 49–56

[1] - ^ a b c d e Baer, Susan (April 1, 1998). "Founding, enduring feminist Bella Abzug is dead at 77 'Battling Bella' served three terms in House". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 20, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Faber, Doris. Bella Abzug. Lothrup, Lee and Shepard, 1976. pp. 61–69. Juvenile book.

- ^ a b Maria Braden (1996). Women Politicians and the Media. University Press of Kentucky. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-8131-0869-8. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Bella Abzug, 77, Congresswoman And a Founding Feminist, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ "Narrative: The Task Force's commitment to ending discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans has a long history". National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Abzug, Bella S. (May 29, 1973). "H.R.8163 - 93rd Congress (1973-1974): Equal Credit Opportunity Act". www.congress.gov. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Mahler, Jonathan (2005). Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning : 1977, baseball, politics, and the battle for the soul of a city (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 69–70. ISBN 0-374-17528-4. OCLC 56057911.

- ^ Rozensky, Jordyn. "Halloween: JWA Style". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Veith, George (2012). Black April: The fall of South Vietnam 1973–75. Encounter Books. p. 122. ISBN 9781594035722.

- ^ Zion, Noam Sachs; Spectre, Barbara (2000). A different light: the Hanukkah book of celebration: a how-to guide to a creative candle lighting ceremony: blessings, songs, stories, readings, games and cartoons to engage adults, teenagers and children on each of the eight nights. New York: Devora Pub. ISBN 9781930143319.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (December 17, 1991). "U.N. Repeals Its '75 Resolution Equating Zionism With Racism". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Morris, Stephen J. (April 29, 2005). "Lessons From the Fall of Saigon". Wall Street Journal – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ "ABZUG, Bella Savitzky". History Art & Archives: US House of Representatives. Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Fowler, Glenn (February 18, 1978). "Green's Victory Is Official, but Mrs. Abzug is Silent". New York Times. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ "Bella Abzug Biography". BIOGRAPHY. A&E Television Network. Archived from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ Bella Abzug (1972). Bella: Ms. Abzug Goes to Washington. Saturday Review Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-8415-0154-8. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ Bella Abzug and Mim Kelber (1984). The Gender Gap: Bella Abzug's Guide to Political Power for American Women. Houghton Mifflin. p. 79. ISBN 0-395-36181-8. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ "The National Women's Conference in Houston, 1977". Uic.edu. January 9, 1974. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ Halloran, Richard (January 14, 1979). "23 Leave Committee Over Abzug Dismissal; 23 on Carter's Committee Resign Over His Ouster of Mrs. Abzug; Questions His 'Rationality'; In Support of Carter; No Endorsement Now". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ "PunʞLawyer". Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ Velez, Denise (March 14, 2016). "They Call me 'Battling Bella'". SandiegoFreePress.org. San Diego Free Press. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ a b "Bella Abzug". Teaching Tolerance. Southern Poverty Law Center. August 7, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ "Bella Abzug at the 42nd Session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women". March 16, 1998. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Mansnerus, Laura (April 1, 1998). "Bella Abzug, 77, Congresswoman And a Founding Feminist, Is Dead". The New York Times.

- ^ Resting Places: The Burial Places of 14,000 Famous Persons, by Scott Wilson

- ^ "Women in Congress 1917–2006" (PDF). GovInfo. US Government Publishing Office. p. 447. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ 'NYC Comptroller Candidate Scott Stringer Enjoys Celebrity Support,' The Jewish Voice, August 21, 2013

- ^ Congresswoman Bella Abzug: Good Person and Changemaker

- ^ "What's the congressional gym like?". Slate. June 13, 2011. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022.

- ^ "PPFA Margaret Sanger Award Winners". Planned Parenthood. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Bella Abzug Leadership Institute - BALI". www.abzuginstitute.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012.

- ^ BALI News and Events Archived October 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine published online, Fall 2007.

- ^ Zorthian, Julia (March 8, 2017). "International Women's Day: 50 Who Made US Political History". Time. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ "Bella Abzug Park News – NYC PARKS ANNOUNCES THE RENAMING OF HUDSON YARDS PARK IN HONOR OF ACTIVIST, CONGRESSWOMAN BELLA ABZUG : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ "Bella Abzug Street co-naming Flyer" (PDF).

- ^ "A Laugh, A Tear, A Mitzvah | KQED". KQED Public Media. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Williams, Alex (March 19, 2014). "Riding the Wave of 'Girls'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Golembewski, Chris Kaye, Vanessa. "39 Moments, 40 Crazy Seasons". www.refinery29.com. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New York: A Documentary Film, retrieved March 1, 2019

- ^ Wulf, Steve (March 23, 2015). "Supersisters: Original Roster". Espn.go.com. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Terry, Cliffor (January 16, 1987). "Maclaine Leaves Little On 'Limb'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Stasio, Marilyn (October 23, 2019). "Off Broadway Review: Harvey Fierstein's 'Bella Bella'".

- ^ a b Pollitt, Katha (April 30, 2020). "Why Did the ERA Die? FX's 'Mrs. America' Has Some Answers". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Donnelly, Matt (February 13, 2020). "Julie Taymor's Gloria Steinem Biopic 'The Glorias' Sells to LD Entertainment, Roadside Attractions". Variety. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (August 8, 2007). "RReview: 'NY77: The Coolest Year in Hell'". Variety. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Levy, Alan H. (2013) The Political Life of Bella Abzug, 1920–1976: Political Passions, Women's Rights, and Congressional Battles (2013), excerpt and text search; coverage to 1976

- Levy, Alan H. The Political Life of Bella Abzug, 1976–1998: Electoral Failures and the Vagaries of Identity Politics (Lexington Books, 2013)

- Mahler, Jonathan (2005). Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning: 1977, baseball, politics, and the battle for the soul of a city. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780312424305.

- Thom, Mary; Levine, Suzanne Braun (2007). Bella Abzug: how one tough broad from the Bronx fought Jim Crow and Joe McCarthy-- : an oral history. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374531492.

- Zarnow, Leandra (2019). Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674737488.

- Zarnow, Leandra (2011), "The legal origin of "the personal is political": Bella Abzug and sexual politics in cold war America", in Laughlin, Kathleen A.; Castledine, Jacqueline L. (eds.), Breaking the wave: women, their organizations, and feminism, 1945–1985, New York: Routledge, pp. 28–46, ISBN 9780415874007

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Bella Abzug at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Bella Abzug at Wikiquote Media related to Bella Abzug at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bella Abzug at Wikimedia Commons- United States Congress. "Bella Abzug (id: A000018)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Bella!, 2020 Documentary Feature Film

- About Bella Abzug (on the website of the Bella Abzug Leadership Institute)

- Blanche Wiesen Cook, an entry about Bella Abzug from the Jewish Women's Archive

- "Bella Abzug". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- Bella Abzug at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- FBI file on Bella S. Abzug at the Internet Archive

- Bella Abzug at the National Women's Hall of Fame

- 1920 births

- 1998 deaths

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 20th-century American legislators

- 20th-century American women politicians

- American feminists

- American pacifists

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- American abortion-rights activists

- American women's rights activists

- American Zionists

- Columbia Law School alumni

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state)

- Female members of the United States House of Representatives

- Hunter College alumni

- Jewish members of the United States House of Representatives

- Jewish American women in politics

- Jewish Theological Seminary of America alumni

- Lawyers from New York City

- LGBTQ rights activists from New York (state)

- People from the Upper East Side

- Politicians from Manhattan

- Politicians from the Bronx

- Women in New York (state) politics

- Writers from Manhattan

- Jewish American people in New York City politics

- 20th-century American women lawyers

- Orthodox Jewish feminists

- 20th-century American Jews

- Equal Rights Amendment activists

- Candidates in the 1976 United States elections

- 20th-century New York (state) politicians