Abilene, Kansas

Abilene, Kansas | |

|---|---|

City and County seat | |

Aerial view of Abilene (2013) | |

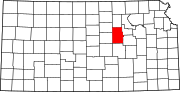

Location within Dickinson County and Kansas | |

| |

| Coordinates: 38°55′23″N 97°13′31″W / 38.92306°N 97.22528°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Dickinson |

| Founded | 1857 |

| Incorporated | 1869[2] |

| Named for | Luke 3:1 (bible) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Brandon L. Rein [citation needed] |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.76 sq mi (12.34 km2) |

| • Land | 4.76 sq mi (12.33 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,145 ft (349 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 6,460 |

| • Density | 1,400/sq mi (520/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 67410 |

| Area code | 785 |

| FIPS code | 20-00125 |

| GNIS ID | 485539[1] |

| Website | abilenecityhall.com |

Abilene (pronounced /ˈæbɪliːn/)[6] is a city in and the county seat of Dickinson County, Kansas, United States.[1] As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460.[4][5] It is home of The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum and the Greyhound Hall of Fame.

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

In 1803, most of modern Kansas was secured by the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1854, the Kansas Territory was organized, then in 1861 Kansas became the 34th U.S. state.

In 1857, Dickinson County was founded and Abilene began as a stage coach stop, established by Timothy Hersey and named Mud Creek. It was not until 1860 that it was named Abilene, from a passage in the Bible (Luke 3:1), meaning "grassy plains".[2]

In 1867, the Kansas Pacific Railway (Union Pacific) pushed westward through Abilene. In the same year, Joseph G. McCoy purchased 250 acres of land north and east of Abilene, on which he built a hotel, the Drover's Cottage, stockyards equipped for 2,000 heads of cattle, and a stable for their horses. The Kansas Pacific put in a spur line at Abilene that enabled the cattle cars to be loaded and sent on to their destinations. The first twenty carloads left September 5, 1867, en route to Chicago, Illinois, where McCoy was familiar with the market.[7] The town grew quickly and became the first "cow town" of the west.[8]

McCoy encouraged Texas cattlemen to drive their herds to his stockyards. From 1867 to 1871, the Chisholm Trail ended in Abilene, bringing in many travelers and making Abilene one of the wildest towns in the west.[9][10] The stockyards shipped 35,000 head in 1867 and became the largest stockyards west of Kansas City, Kansas. In 1871, more than 5,000 cowboys herded from 600,000 to 700,000 cows to Abilene and other Kansas railheads.[2][11][12] Another source reports 440,200 head of cattle were shipped out of Abilene from 1867 to 1871.[13] As railroads were built further south, the end of the Chisholm Trail was slowly moved south toward Caldwell, while Kansas homesteaders concerned with cattle ruining their farm crops moved the trail west toward and past Ellsworth.

Town marshal Tom "Bear River" Smith was initially successful policing Abilene, often using only his bare hands. He survived 2 assassination attempts during his tenure. However, he was murdered and decapitated on November 2, 1870. Smith wounded 1 of his 2 attackers during the shootout preceding his death, and both suspects received life in prison for the offense.[8] He was replaced by Wild Bill Hickok in April 1871.[2] Hickok's time in the job was short. While the marshal was standing off a crowd during a street brawl, gambler Phil Coe took two shots at Hickok, who returned fire, killing Coe but Hickok then accidentally shot his friend and deputy, Mike Williams,[14] who was coming to his aid. Hickok lost his job two months later in December.

In 1880, Conrad Lebold built the Lebold Mansion. Lebold was one of the early town developers and bankers from 1869 through 1889. The Hersey dugout can still be seen in the cellar. The house is now a private residence.[15] A marker outside credits the name of the town being given by opening a Bible and using the first place name pointed to.

In 1887, Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway built a branch line from Neva (3 miles (4.8 km) west of Strong City) through Abilene to Superior, Nebraska. In 1996, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway merged with Burlington Northern Railroad and renamed to the current BNSF Railway. Most locals still refer to this railroad as the Santa Fe.

In 1890, Dr. A.B. Seelye founded the A.B. Seelye Medical Company. Seelye developed over 100 products for the company including "Wasa-Tusa",[16][failed verification] an Indian name meaning to heal.

20th century

[edit]

Abilene became home to Dwight D. Eisenhower when his family moved to Abilene from Denison, Texas in 1892. Eisenhower attended elementary school through high school in Abilene, graduating in 1909. The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum is the burial site of President Eisenhower, his wife, Mamie, and their first-born son Doud Dwight.[17]

Geography

[edit]Abilene is on the north side of the Smoky Hill River[2] in the Flint Hills region of the Great Plains.[18] Mud Creek, a tributary of the Smoky Hill, flows south through the city.[19] Located in North Central Kansas at the intersection of Interstate 70 and K-15, Abilene is approximately 27 mi (43 km) east of Salina, Kansas, 94 mi (151 km) north of Wichita, and 139 mi (224 km) west of Kansas City.[18][20]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 4.68 square miles (12.12 km2), all of it land.[21]

Climate

[edit]Located in the transition zone between North America's humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) and humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa) zones, Abilene experiences hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters. In the spring, severe thunderstorms bring the threat of tornadoes and hail. The hottest temperature recorded in Abilene was 113 °F (45.0 °C) on July 13, 1954 and July 15, 1954, while the coldest temperature recorded was −29 °F (−33.9 °C) on February 12, 1899.[22]

| Climate data for Abilene, Kansas, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

84 (29) |

95 (35) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

111 (44) |

113 (45) |

112 (44) |

113 (45) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

74 (23) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 63.9 (17.7) |

71.0 (21.7) |

81.0 (27.2) |

87.4 (30.8) |

93.1 (33.9) |

100.7 (38.2) |

105.2 (40.7) |

102.8 (39.3) |

96.9 (36.1) |

89.7 (32.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

65.7 (18.7) |

106.5 (41.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.2 (6.2) |

48.6 (9.2) |

59.7 (15.4) |

69.7 (20.9) |

78.9 (26.1) |

89.4 (31.9) |

94.4 (34.7) |

92.1 (33.4) |

84.2 (29.0) |

71.2 (21.8) |

57.1 (13.9) |

45.4 (7.4) |

69.5 (20.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 32.5 (0.3) |

36.9 (2.7) |

47.3 (8.5) |

57.2 (14.0) |

66.8 (19.3) |

77.1 (25.1) |

81.9 (27.7) |

79.8 (26.6) |

71.6 (22.0) |

58.8 (14.9) |

45.6 (7.6) |

35.0 (1.7) |

57.5 (14.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

34.9 (1.6) |

44.7 (7.1) |

54.7 (12.6) |

64.8 (18.2) |

69.4 (20.8) |

67.4 (19.7) |

58.9 (14.9) |

46.4 (8.0) |

34.1 (1.2) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

45.6 (7.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.6 (−16.9) |

6.1 (−14.4) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

38.9 (3.8) |

52.1 (11.2) |

59.0 (15.0) |

56.5 (13.6) |

42.5 (5.8) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

16.7 (−8.5) |

6.7 (−14.1) |

−2.3 (−19.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −20 (−29) |

−29 (−34) |

−9 (−23) |

9 (−13) |

27 (−3) |

34 (1) |

44 (7) |

41 (5) |

23 (−5) |

16 (−9) |

−6 (−21) |

−24 (−31) |

−29 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.86 (22) |

1.43 (36) |

2.23 (57) |

3.26 (83) |

5.20 (132) |

4.18 (106) |

4.75 (121) |

4.27 (108) |

2.54 (65) |

2.47 (63) |

1.59 (40) |

1.50 (38) |

34.28 (871) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.1 (10) |

2.8 (7.1) |

1.7 (4.3) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.0 (2.5) |

2.2 (5.6) |

12.2 (30.52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.9 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 10.2 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 78.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 7.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA[23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[22] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Abilene remains a cattle yard town, loading onto the rail system, along with grain and other crops.[2]

It is the birthplace of Sprint Telecommunications.[24]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,360 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,547 | 50.3% | |

| 1900 | 3,507 | −1.1% | |

| 1910 | 4,118 | 17.4% | |

| 1920 | 4,895 | 18.9% | |

| 1930 | 5,658 | 15.6% | |

| 1940 | 5,671 | 0.2% | |

| 1950 | 5,775 | 1.8% | |

| 1960 | 6,746 | 16.8% | |

| 1970 | 6,661 | −1.3% | |

| 1980 | 6,572 | −1.3% | |

| 1990 | 6,242 | −5.0% | |

| 2000 | 6,543 | 4.8% | |

| 2010 | 6,844 | 4.6% | |

| 2020 | 6,460 | −5.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census 2010-2020[5] | |||

2020 census

[edit]The 2020 United States census counted 6,460 people, 2,797 households, and 1,675 families in Abilene.[25][26] The population density was 1,356.6 per square mile (523.8/km2). There were 3,137 housing units at an average density of 658.8 per square mile (254.3/km2).[26][27] The racial makeup was 91.93% (5,939) white or European American (89.52% non-Hispanic white), 0.87% (56) black or African-American, 0.36% (23) Native American or Alaska Native, 0.34% (22) Asian, 0.12% (8) Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, 1.47% (95) from other races, and 4.91% (317) from two or more races.[28] Hispanic or Latino of any race was 5.65% (365) of the population.[29]

Of the 2,797 households, 26.9% had children under the age of 18; 44.7% were married couples living together; 30.0% had a female householder with no spouse or partner present. 35.8% of households consisted of individuals and 18.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.[26] The average household size was 2.1 and the average family size was 2.9.[30] The percent of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher was estimated to be 21.2% of the population.[31]

23.1% of the population was under the age of 18, 7.4% from 18 to 24, 22.3% from 25 to 44, 24.6% from 45 to 64, and 22.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 106.9 males.[26] For every 100 females ages 18 and older, there were 111.9 males.[26]

The 2016-2020 5-year American Community Survey estimates show that the median household income was $47,829 (with a margin of error of +/- $10,161) and the median family income was $69,815 (+/- $11,480).[32] Males had a median income of $36,933 (+/- $6,402) versus $21,540 (+/- $3,802) for females. The median income for those above 16 years old was $30,625 (+/- $4,869).[33] Approximately, 4.8% of families and 8.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.2% of those under the age of 18 and 8.5% of those ages 65 or over.[34][35]

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census, there were 6,844 people, 2,878 households, and 1,781 families residing in the city.[36] The population density was 1,463.6 inhabitants per square mile (565.1/km2). There were 3,143 housing units at an average density of 671.6 per square mile (259.3/km2). The city's racial makeup was 94.9% White, 0.9% African American, 0.4% American Indian, 0.2% Asian, 1.1% from some other race, and 2.4% from two or more races. 4.7% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.[37]

There were 2,878 households, of which 31.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.3% were married couples living together, 4.0% had a male householder with no wife present, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.1% were non-families. 33.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33, and the average family size was 2.97.[37]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.7% under the age of 18, 6.9% from 18 to 24, 23.7% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 19.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.2 males age 18 and over.[37]

The city's median household income was $48,115, and the median family income was $61,146. Males had a median income of $42,332 versus $29,325 for females. The city's per capita income was $21,820. About 7.3% of families and 10.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.1% of those under age 18 and 15.1% of those age 65 or over.[37]

Education

[edit]The community is served by Abilene USD 435 public school district.

Transportation

[edit]

Interstate 70 and U.S. Route 40 run concurrently east–west immediately north of Abilene, intersecting highway K-15, which runs north–south through the city.[18]

Abilene Municipal Airport is on the city's southwest side. Publicly owned, it has one asphalt runway and is used predominantly for general aviation.[38]

The Kansas Pacific (KP) line of the Union Pacific Railroad runs east–west through the city.[19][39] It intersects a BNSF Railway line which enters the city from the east and then turns north.[40]

The city of Abilene provided demand responsive transport.[41]

Media

[edit]Abilene has one daily newspaper, The Abilene Reflector-Chronicle.[42]

Radio

[edit]The following radio stations are licensed to Abilene:

AM

| Frequency | Callsign[43] | Format[44] | City of License | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1560 | KABI | Adult Standards/MOR | Abilene, Kansas | - |

FM

| Frequency | Callsign[45] | Format[46] | City of License | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 94.1 | K231AW | Religious | Abilene, Kansas | AFR; Translator of KAKA, Salina, Kansas[47] |

| 98.5 | KSAJ-FM | Oldies | Abilene, Kansas | Broadcasts from Salina, Kansas[48] |

Television

[edit]Abilene is in the Wichita-Hutchinson, Kansas television market.[49]

Points of interest

[edit]

- Abilene and Smoky Valley Railroad - A tourist railroad based out of the old Rock Island train depot in Old Abilene Town; it hauls passengers between Abilene and Enterprise.[50]

- Eisenhower Presidential Center and the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum.[1] - Contains murals depicting President Eisenhower's life, painted by artists, Louis George Bouché and Ross Moffett in 1954.

- Great Plains Theatre - Originally First Presbyterian Church, built in 1881, Landmarked, and is now a live professional theatre, and movie theatre. [2]

- Greyhound Hall of Fame - Near the Eisenhower Presidential Library, the hall exhibits the history of the greyhound breed and of greyhound racing.

- Heritage Center of Dickinson County - Two museums including the Historical Museum and the Museum of Independent Telephony. The Museum of Independent Telephony tells the story of C. L. Brown, whose independent Brown Telephone Company grew to become Sprint Corporation[51] and then T-Mobile.

- Lebold Mansion - National Register Property listed in 1973. Built in 1880 in the Italianate Tuscan villa style. This decorative arts museum was once home to one of the finest collections of American Victorian antiques and artifacts. However, the museum closed to all tours in June 2010 and was sold to new owners as a private residence on 9/15/10.[3] Archived August 28, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Old Abilene Town - Constructed as a replica historic district, beginning in the late 1950s, it includes several original buildings that have been moved from their original locations.[52]

- A. B. Seelye House and Museum - A Georgian style mansion built in 1905 at a cost of $55,000. The 25 room mansion contains the original furniture and Edison light fixtures. The Patent Medicine Museum contains many artifacts of the A.B. Seelye Medical Company. [4] Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it is a museum showcasing Seelye, an advocate of patent medicines.[53]

- Kansas Historical Marker - Historic Abilene, on south Sixth Street.[54]

Cultural

[edit]Cowboy-era Abilene is the fictional setting for the Randolph Scott-starring 1946 film Abilene Town, which in turn became the inspiration behind the 1963 hit song "Abilene", recorded by George Hamilton IV.

British singer-songwriter John Cale's song "Buffalo Ballet" from his 1975 album "Fear" reflects a cynical view of the town's history from the days it was "young and gay" until it "drowned in wealth and pain", as an example of the expansion of the American Frontier.

The main storyline of western video game Call of Juarez: Gunslinger is at Abilene.

The much larger city of Abilene, Texas takes its name from Abilene, Kansas.[2][55]

Notable people

[edit]

Old West figures who lived in Abilene during its period as a cowtown included Wild Bill Hickok, cattle baron Joseph McCoy, gambler Phil Coe, marshal Tom "Bear River" Smith, gunfighters Pat Desmond, John Wesley Hardin, and Ben Thompson, and Thompson's sister-in-law Libby, a prostitute and dance hall girl.[56][57] President of the United States and five-star general Dwight D. Eisenhower grew up in Abilene as did his brothers Edgar, Earl, and Milton.[58][59] Eisenhower is buried in Abilene, along with his wife Mamie and their eldest son Doud, on the grounds of his presidential library.[60]

Other notable individuals who have lived in Abilene include these:

- C. Olin Ball, food scientist, inventor[61]

- Harry Beaumont, Oscar-nominated film director[62]

- Joseph Burton, U.S. Senator from Kansas[63]

- Steve Doocy, journalist, author[64]

- Joe Engle, pilot and NASA Astronaut

- Marlin Fitzwater, former Press Secretary of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush.[65]

- Edward Little, U.S. Representative from Kansas[66]

- Deane Malott, university administrator[67]

- Frank Parent, California court judge[68]

- Mike Racy, commissioner for MIAA previously vice president for NCAA

- Everett Stewart, World War II flying ace[69]

- Hy Vandenberg, Major League Baseball pitcher[70]

- Cody Whitehair, center for the Chicago Bears

Sister cities

[edit]See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Dickinson County, Kansas

- Abilene High School

- Abilene Trail

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Abilene, Kansas

- ^ a b c d e f g Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abilene". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Profile of Abilene, Kansas in 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts; Abilene, Kansas; Population, Census, 2020 & 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ William Allen White School of Journalism and Public Information (1955). A pronunciation guide to Kansas place names. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. p. 7. hdl:2027/mdp.39015047651115.

- ^ Smith, Jessica (2013). "Morality and Money: A Look at how the Respectable Community Battled the Sporting Community over Prostitution in Kansas Cowtowns, 1867-1885" (PDF). Kansas State University.

- ^ a b Joseph G. Rosa (1979). They Called Him Wild Bill. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 172–206. ISBN 978-0-8061-1538-2. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "Chisholm Trail". Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. at the Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- ^ Route of the Chisholm cattle trail in Kansas; Kansas Historical Society, 1960s.

- ^ Gard, Wayne (1969) [1954]. The Chisholm Trail. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 155–156. LCCN 54-6204.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (1997). Mulroy, Kevin (ed.). Trail of the Wild West. Kingsport, TN: National Geographic Society. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0792270218.

- ^ Kansas Pacific Railway Company. Guide Map of the Best and Shortest Cattle Trail to the Kansas Pacific Railway; Kansas Pacific Railway Company; 1875.

- ^ "Officer Down Memorial Page (ODMP)". July 3, 2017. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017.

- ^ "Lebold Mansion, Abilene". Kansas Sampler Foundation. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "The historic Seelye Mansion, Abilene, Kansas". Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "Flint Hills of Kansas Shopping, Dining, & Accommodations". March 8, 2016. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c "2003-2004 Official Transportation Map" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. 2003. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "General Highway Map - Dickinson County, Kansas" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. July 1, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "City Distance Tool". Geobytes. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ a b "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Topeka". National Weather Service. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Abilene, KS". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ "Fast facts". Archived from the original on December 31, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: HOUSEHOLD TYPE". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "US Census Bureau, Table DP1: PROFILE OF GENERAL POPULATION AND HOUSING CHARACTERISTICS". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P1: RACE". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P2: HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table S1101: HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table S1501: EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table S1903: MEDIAN INCOME IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS (IN 2020 INFLATION-ADJUSTED DOLLARS)". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table S2001: EARNINGS IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS (IN 2020 INFLATION-ADJUSTED DOLLARS)". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table S1701: POVERTY STATUS IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table S1702: POVERTY STATUS IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS OF FAMILIES". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "2010 City Population and Housing Occupancy Status" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "K78 - Abilene Municipal Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "UPRR Common Line Names" (PDF). Union Pacific Railroad. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Kansas Operating Division" (PDF). BNSF Railway. January 1, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "Abilene, KS - Public Transportation". Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ "About this Newspaper: Abilene reflector-chronicle". Chronicling America. Library of Congress. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "AMQ AM Radio Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "Station Information Profile". Arbitron. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "FMQ FM Radio Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "Radio Stations in Abilene, Kansas". Radio-Locator. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ^ "K231AW-FM Radio Station Information". Radio-Locator. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". KSAJ-FM. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Kansas TV Market Map". EchoStar Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ Abilene & Smoky Valley Excursion Train, Kansas Department of Commerce. Accessed 2009-04-14.

- ^ "Telephone Museum". heritagecenterdk.com. Archived from the original on November 19, 2005. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Historic Old Abilene Town Archived July 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Abilene. Accessed 2009-04-14.

- ^ Seelye Mansion Archived January 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Abilene. Accessed 2009-04-14.

- ^ "Kansas Historical Markers - Kansas Historical Society". www.kshs.org.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 22. ISBN 0-7884-0579-9.

- ^ Gray, Jim. "Abilene History". Kansas Cattle Towns. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Weiser, Kathy (2008). "Old West Legends - Texas Madam Squirrel Tooth Alice". Legends of America. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Abilene Years". Eisenhower Presidential Center. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "President Dwight D. Eisenhower". Internet Accuracy Project. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Final Post". Eisenhower Presidential Center. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Pehanich, Mike (September 10, 2003). "Hail to the innovators". Food Engineering. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Hischak, Thomas (2008). The Oxford Companion to the American Musical. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780195335330.

- ^ "Burton, Joseph Ralph". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Five Minutes with FOX & Friends". Fox News Channel. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Roberts, Steven V. (November 29, 1988). "MAN IN THE NEWS: MAX MARLIN FITZWATER; The Face Is Familiar Max Marlin Fitzwater". The New York Times. p. 6. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- ^ "Little, Edward Campbell". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "President Emeritus Malott dies at 98". Cornell Chronicle. September 19, 1996. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "F. D. Parent, Retired City Judge, Dies at 81: Inglewood Man, Who Served on Bench 28 Years, Coached Eisenhower in High School.", Los Angeles Times, p. B1, June 20, 1960

- ^ Hatch, Gardner N.; Winter, Frank H. (1993), P-51 Mustang, Nashville: Turner Publishing Company, p. 135

- ^ "Hy Vandenberg Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Interactive City Directory". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]- City of Abilene

- Abilene - Directory of Public Officials

- Historic Images of Abilene, Special Photo Collections at Wichita State University Library

- Kansas Photo Tour - Eisenhower Center

- Seelye Mansion on YouTube, from Hatteberg's People on KAKE TV news

- Abilene city map, KDOT