Primal Fear (film)

| Primal Fear | |

|---|---|

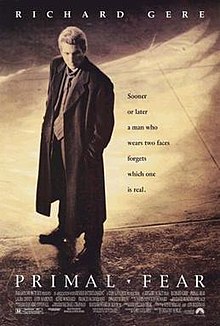

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gregory Hoblit |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Primal Fear by William Diehl |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by | David Rosenbloom |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[1] |

| Box office | $102.6 million[2] |

Primal Fear is a 1996 American legal mystery crime thriller film directed by Gregory Hoblit, based on the 1993 novel of the same name by William Diehl, written by Steve Shagan and Ann Biderman. It stars Richard Gere, Laura Linney, John Mahoney, Alfre Woodard, Frances McDormand and Edward Norton in his film debut. The film follows a Chicago-based defense attorney who believes that his client, an altar boy, is not guilty of murdering a Catholic bishop.

The film was a box office success and received mixed-to-positive reviews, with Norton's performance earning critical praise. Norton won the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture, and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor and the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role.[3]

Plot

[edit]Martin Vail is an arrogant Chicago defense attorney, known for his undesirable but high-profile clients, including mob boss Joey Piñero. Fond of the spotlight, Vail is profiled for a magazine cover story and attempts to rekindle a casual relationship with his former colleague, prosecutor Janet Venable.

One day, beloved Archbishop Rushman is murdered in his bedroom and his body mutilated. Aaron Stampler, a 19-year-old altar boy from Kentucky, is caught fleeing the scene covered in blood and charged with murder. Vail offers to defend him pro bono, and the meek, stuttering Aaron claims he is innocent but is prone to amnesia. Vail believes Aaron, while the state's attorney, John Shaughnessy, assigns Venable to prosecute the case and pursue the death penalty.

At Aaron's apartment, Vail's investigator Tommy Goodman is attacked by another altar boy, Alex, who flees. Neuropsychologist Dr. Molly Arrington interviews Aaron for hours about his difficult childhood, his memory lapses, and his missing girlfriend Linda. With help from Piñero, Vail discovers that powerful civic leaders, including Shaughnessy, lost millions in real estate investments due to Rushman's decision not to develop church-owned land. In court, a message carved into Rushman's chest is linked to a passage from The Scarlet Letter, which denounced the archbishop as "two-faced".

Vail and Goodman track down Alex, who was searching for an incriminating VHS cassette. Stealing the tape from the archbishop's closet, Vail and his team discover footage of one of many encounters filmed by the archbishop, in which he coerces Aaron, Linda, and Alex to engage in sexual acts on threat of eviction from their group home. Vail angrily confronts Aaron about concealing information from him, but Aaron denies the accusations, becoming increasingly distressed as Vail continues to press him. Aaron's demeanor abruptly shifts from deferential to aggressive, and he chastises Vail for "scaring off" Aaron. This violent personality, Roy, admits to killing the archbishop but threatens Vail not to introduce the tape at trial. Suddenly, he reverts back to Aaron's docile personality, with no recollection of the episode.

Dr. Arrington concludes that Aaron has dissociative identity disorder caused by years of abuse at the hands of his father and, later, Rushman. Conflicted, Vail knows that he could acquit his client via an insanity defense, but legal rules would not allow him to change his strategy mid-trial. He delivers the evidence anonymously to Venable, forcing her to use the tape as proof of Aaron's motive, at the risk of tarnishing the archbishop and generating sympathy for Aaron. Shaughnessy demands that she destroy the evidence, but she refuses and introduces it in court.

Piñero is discovered murdered, and Vail surprises the court by calling Shaughnessy as a witness. Vail suggests Shaughnessy resented the archbishop for stopping the $60 million land development, and accuses him of concealing previous evidence of the archbishop's sexual predation, and for being complicit in Piñero's death. Judge Shoat intervenes, striking the line of questioning from the record and fining Vail for using the courtroom as a stage for his own vendettas. She also dismisses Dr. Arrington's testimony as it leans too close to an insanity plea. Vail then calls Aaron to the stand, intentionally triggering his memories of his father's abuse. Venable begins a challenging cross-examination, in which Aaron suddenly becomes Roy, screaming obscenities and assaulting Venable before he is subdued. The judge dismisses the jury in favor of a bench trial to declare Aaron not guilty by reason of insanity.

A shaken Venable rejects Vail's advances, and Vail informs Aaron that he will be remanded to a psychiatric hospital for treatment with a strong possibility of release. A grateful Aaron thanks Vail and asks him to apologize to Venable for the injuries to her neck, leading Vail to realize that Aaron was aware of his actions during the attack. Aaron commends the attorney for his insight, then brags about having murdered Linda and Rushman without remorse and faking having multiple personalities. When Vail asks if the Roy persona was a fake the whole time, the murderer corrects him by stating: "There never was an Aaron, Counselor." Stunned and disillusioned, Vail leaves the courthouse, but does so through a discreet back entrance to avoid the attention and publicity he once sought.

Cast

[edit]- Richard Gere as defense attorney Martin Vail

- Edward Norton as defendant Aaron Stampler / Roy

- Laura Linney as prosecutor Janet Venable

- John Mahoney as state's attorney John Shaughnessy

- Alfre Woodard as Judge Miriam Shoat

- Frances McDormand as Dr. Molly Arrington

- Terry O'Quinn as Yancy

- Andre Braugher as Vail's investigator Tommy Goodman

- Steven Bauer as Joey Pinero, a local crime boss and Vail's client

- Joe Spano as Stenner

- Tony Plana as Martinez

- Azalea Davila as victim Linda

- Stanley Anderson as Archbishop Rushman

- Maura Tierney as Vail's assistant Naomi

- Jon Seda as former altar boy Alex

- Reg Rogers as Jack Connerman

Several Chicago television news personalities made cameos as themselves as they deliver reports about the case, including WLS's Diann Burns and Linda Yu, WBBM-TV's Mary Ann Childers, Lester Holt and Jon Duncanson, and WGN-TV's Bob Jordan and Randy Salerno.

Production

[edit]Pedro Pascal auditioned for a role in the film.[4] Paramount wanted Leonardo DiCaprio as Aaron Stampler, he was offered the role but declined as he found the script "problematic".[5][6] Casting calls were set in California and England where 2,100 actors were seen for the role of Aaron, including Matt Damon and James Van Der Beek[7][8][9] Connie Britton auditioned for the role of Naomi, which eventually went to Maura Tierney.[5]

Soundtrack

[edit]The soundtrack includes the Portuguese fado song "Canção do Mar" sung by Dulce Pontes.

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was released on April 5, 1996 and opened in the #1 spot, remaining there for three consecutive weeks.[10][2] It grossed $56.1 million domestically and $46.5 million internationally for a total worldwide gross of $102.6 million.[2]

Home media

[edit]The film was released to VHS and LaserDisc on October 15, 1996.[11] On October 21, 1998, it was released to DVD.[12]

Paramount released Primal Fear on Blu-ray on March 10, 2009.[13] The Blu-ray includes an audio commentary track by director Gregory Hoblit, writer Ann Biderman, producer Gary Lucchesi, executive producer Hawk Koch, and casting director Deborah Aquila, as well as the featurettes "Primal Fear: The Final Verdict", "Primal Fear: Star Witness-Casting Edward Norton", and "The Psychology of Guilt".

Reception

[edit]

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes reports an approval rating of 77% based on 48 reviews, with an average rating of 6.8/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Primal Fear is a straightforward, yet entertaining thriller elevated by a crackerjack performance from Edward Norton".[14] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, lists the film with a weighted average score of 47/100 based on 18 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[15] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore awarded the film an average grade of B+ on an A+-to-F scale.[16]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote that the film has a "good deal of surface charm" but "the story relies on an overload of tangential subplots to keep it looking busy".[17] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times awarded Primal Fear three and a half stars, writing that "the plot is as good as crime procedurals get, but the movie is really better than its plot because of the three-dimensional characters". Ebert described Gere's performance as one of the best in his career, praised Linney for rising above what might have been a stock character and applauded Norton for offering a "completely convincing" portrayal.[18]

The film spent three weekends at the top of the U.S. box office.[2]

Accolades

[edit]The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Aaron Stampler – Nominated Villain[36]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Courtroom Drama Film[37]

See also

[edit]- Mental illness in films

- Trial movies

- Plot twist

- Deewangee (2002), a Hindi film influenced by Primal Fear.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ "15 Highest-Earning Edward Norton Movies Of All Time (& How Much They Made)". Screen Rant. January 3, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Primal Fear". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "Primal Fear". Golden Globes. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "Pedro Pascal". September 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "Role Recall: Edward Norton on landing 'Primal Fear' after Leo passed, making 'Fight Club' funny and who's his favorite Bruce Banner". November 2019.

- ^ https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-04-16-ca-59082-story.html

- ^ https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-04-16-ca-59082-story.html

- ^ https://www.vanityfair.com/news/1997/12/matt-damon-199712

- ^ https://ew.com/article/2014/03/25/james-van-der-beek-dawsons-creek-varsity-blues/

- ^ "Domestic 1996 Weekend 14". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ King, Susan (August 16, 1996). "'Letterbox' Brings Wide Screen Home". Los Angeles Times. p. 96. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Primal Fear – Releases". AllMovie. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ "Primal Fear (Hard Evidence Edition) [Blu-ray]". Amazon. March 10, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ "Primal Fear (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ "Primal Fear". Metacritic.

- ^ "Primal Fear (1996) B+". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 3, 1996). "A Murdered Archbishop, Lawyers In Armani". The New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (April 5, 1996). "Primal Fear 1996". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 14, 2018 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "The 69th Academy Awards (1997) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "ASCAP Film & TV Awards Honor Mandel, Wise, Others". Billboard. May 10, 1997. p. 6. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ "BSFC Winners 1990s". bostonfilmcritics.org. July 27, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1997". BAFTA. 1997. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "1996 – 9th Annual Chicago Film Critics Awards". Chicago Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1996". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.

- ^ "1996 FFCC Award Winners". June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Primal Fear – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1990–99". kcfcc.org. December 14, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (December 16, 1996). "Los Angeles Critics Honor 'Secrets and Lies'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ Richmond, Ray (April 18, 1997). "Bard Tops MTV List". Variety. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "New Honors for 'Breaking the Waves'". Los Angeles Times. January 6, 1997. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ "1st Annual Film Awards (1996)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "2009 | Categories | International Press Academy". International Press Academy. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Baumgartner, Marjorie (December 27, 1996). "Fargo, You Betcha; Society of Texas Film Critics Announce Awards". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ^ "SEFCA 1996 Winners". sefca.net. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Ajay Devgns character in Deewangee inspired my role in Red: Krushna Abhishek, India News, Business News | Zee Business". www.zeebiz.com.

External links

[edit]- 1996 films

- 1996 crime thriller films

- 1996 directorial debut films

- 1990s legal thriller films

- 1996 psychological thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American legal drama films

- American psychological thriller films

- American courtroom films

- Films about dissociative identity disorder

- Films scored by James Newton Howard

- Films about lawyers

- Films about religion

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on crime novels

- Films directed by Gregory Hoblit

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films set in Chicago

- Films shot in Chicago

- Films shot in West Virginia

- Films produced by Gary Lucchesi

- American legal thriller films

- American neo-noir films

- Paramount Pictures films

- Rysher Entertainment films

- Works about judgement

- Films about law enforcement

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- English-language crime thriller films