Sakalava rail

| Sakalava rail | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Zapornia |

| Species: | Z. olivieri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zapornia olivieri (Grandidier, G & Berlioz, 1929)

| |

| |

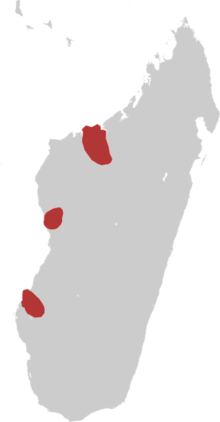

| Distribution of the Sakalava rail | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Amaurornis olivieri (Grandidier & Berlioz, 1929) | |

The Sakalava rail (Zapornia olivieri) is a species of bird in the family Rallidae. It is endemic to western Madagascar. This bird is small with brown upperpart feathers, grey underparts, a yellow bill and red legs.[1]

The habitat of this rail species is freshwater marshes of reed Phragmites mauritianus.[2] It is classified as Endangered and is threatened by habitat loss due to the destruction of wetlands in Madagascar.[2]

Description

[edit]Sakalava rail measures 19 cm with grey underparts, a yellow bill and red eyes.[1] This rail species exhibits some evidence of sexual dimorphism of different body size and colors. Males are smaller, thinner, have rufous-brown upperparts and bright red shanks.[3] Females are larger, have brown-green upperparts and pale pink shanks. Juvenile and immature Sakalava rails look very similar to females.[3] Although 34 microsatellite loci which are polymorphic molecular markers were produced for this species, additional research is needed to confirm sexual dimorphism using DNA or voice analysis.[3][4]

Habitat

[edit]Sakalava rail lives in marshes of open water and dense reedbeds of Phragmites mauritianus.[2] These lotic marshes also contain many floating plant species such as native ferns (Salvinia), water lilies (Nymphaea lotus and Nymphaea nouchali) and invasive water hyacinths (Eichhornia crassipes).[2]

Distribution

[edit]Sakalava rail has a restricted distribution in Madagascar due to a small and fragmented population.[5] This rail species has been historically recorded between the Mahavavy Sud River in the north and the Mangoky river in the south.[3] Its population was estimated at 215 individuals with the largest single population of 62 birds following surveys conducted in 2003–2006.[2] During this study, Sakalava rails were located at five locations: Lake Kinkony, Ampandra, Amparihy, Sahapy and Mandrozo.[2] In 2021, the IUCN Red List estimated that the population ranges between 250 and 999 mature individuals. Although few observations have been made, the species is suggested to have a declining population.[1]

Behavior and ecology

[edit]Sakalava rails are found alone or in pairs. They walk slowly over floating vegetation and turn ferns with their bills to catch prey when feeding.[2] When scared, they run and briefly fly to hide into deep vegetation. They are commonly predated by yellow-billed kite (Milvus aegyptius) and Madagascar coucal (Centropus toulou).[2]

The Sakalava rail's peak breeding period lasts from September to November, but there is some evidence that this rail species could have a longer breeding period lasting year-round.[5] Some active nests and young Sakalava rails have been observed during the wet season in February and March.[2]

Both sexes participate in parental care activities during the breeding season: from building the nest, incubating the eggs, and feeding the chicks.[5] No evidence of cooperative breeding by helpers has been observed for the Sakalava rail.[5]

Vocalizations

[edit]Sakalava rail performs many bird vocalizations. They emit a “tic–tic” or “tic-tic-tic huaw” call while flicking their tail. They also simultaneously communicate with their partner by vocalizing a “truwruru” every 4 to 6 seconds while motionless.[2] Before mating, both males and females stand side-by-side and simultaneously emit a loud “prourourou”.[5] Chicks can also call a loud “kiouw” every 3 to 5 seconds.[2]

Diet

[edit]More than half of Sakalava rail's diet is composed of spiders, while the remaining portion is made up of insects, crustaceans and molluscs found under floating vegetation.[1]

Reproduction

[edit]The male Sakalava 4ail has to perform an elaborate courtship display in order to mate. First, the male leads and presents to the female possible nest sites while calling loudly. The male vocalizes to invite the female to visit the site.[5] Then, the male would carry material and begin building a nest. When the female approves of the site, she would immediately assist in constructing the nest.[5] If she did not find the site suitable, she would not assist in nest construction, which would cause the male to move to another site and repeat this courtship behavior until a suitable nesting site is found.[5]

A breeding pair of Sakalava rail builds a new nest every breeding season. Both sexes participate in building the nest and they usually complete the construction in 3 days.[5] The nest is made of dead Phragmites reeds and is situated 50 to 70 cm above the water.[5] The nest can be built on floating vegetation or inside a deep tunnel of leaves.[5]

Both female and male Sakalava rail incubate the eggs. The egg incubation period usually lasts 16 days and egg-laying occurs from July to September.[5] The clutch size is 2 or 3 eggs of pale cream color with brown spots.[2][5] Both sexes feed the downy black chicks until they reach 40 days of age.[5] The adults then stop providing food and start chasing the precocial chicks out of the nest. At 45 days old, the chicks are completely independent and leave the nest.[5]

Threats

[edit]Sakalava rail is classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List due to the degradation of wetlands in Madagascar. Habitat loss is a major threat to this rail species when the shores of marshes where Sakalava rails nest are converted into rice fields.[1][2] Also, human disturbance degrades the habitat of Sakalava rails when local populations burn and collect Phragmites reeds.[2] Indeed, the surface area occupied by reeds has decreased by 80% between 1949 and 2008 due to increased turbidity from erosion.[6] These wetlands of western Madagascar are also home to five other threatened bird species: Madagascar fish eagle (Haliaeetus vociferoides), Madagascar heron (Ardea humbloti), Madagascar sacred ibis (Threskiornis bernieri), Madagascar teal (Anas bernieri) and the Madagascar plover (Charadrius thoracicus).[7] Conservation actions such as creating protected areas are underway to preserve these ecosystems and their rare bird species.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g BirdLife International. (2021). "Zapornia olivieri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22692654A194884811. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22692654A194884811.en. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rabenandrasana, Marc; Zefania, Sama; Long, Peter; The Seing, Sam; Clémentine Virginie, Marie; Randrianarisoa, Mihaja; Safford, Roger; Székely, Tamas (March 2009). "Distribution, habitat and status of 'Endangered' Sakalava Rail of Madagascar". Bird Conservation International. 19 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1017/S0959270908008058. S2CID 86474531.

- ^ a b c d Rabenandrasana, Marc (February 2007). Conservation biology of Sakalava rail Amaurornis olivieri an Endangered Malagasy water bird and public awareness in Besalampy wetlands complex, Western Madagascar. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Ligue Malgache pour la Protection des Oiseaux.

- ^ Brede, Edward G.; Long, Peter; Zefania, Sama; Rabenandrasana, Marc; Székely, Tamás; Bruford, Michael (2010-02-13). "PCR primers for microsatellite loci in a Madagascan waterbird, the Sakalava Rail (Amaurornis olivieri)". Conservation Genetics Resources. 2 (S1): 273–277. doi:10.1007/s12686-010-9189-2. S2CID 36533079.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Pruvot, Yverlin Z; René de Roland, Lily-Arison; Razafimanjato, Gilbert; Rakotondratsima, Marius PH; Andrianarimisa, Aristide; Thorstrom, Russell (2018-04-03). "Nesting biology and food habits of the endangered Sakalava Rail Amaurornis olivieri in the Mandrozo Protected Area, western Madagascar". Ostrich. 89 (2): 109–115. doi:10.2989/00306525.2017.1317296. S2CID 91135825.

- ^ Andriamasimanana, R (2011-07-19). "Analyses de la dégradation du lac Kinkony pour la conservation du Complexe des Zones Humides Mahavavy - Kinkony, Région Boeny, Madagascar". Madagascar Conservation & Development. 6 (1). doi:10.4314/mcd.v6i1.68061. ISSN 1662-2510.

- ^ Young, H. Glyn; Young, R. P.; Razafindrajao, F.; Aboudou, Abdallah Iahia Bin; Fa, J. E. (2014). "Patterns of waterbird diversity in central western Madagascar: where are the priority sites for conservation?". Wildfowl. 64 (64): 35–53. ISSN 2052-6458.

External links

[edit]- Madagascar country profile by the African Bird Club