Xiangliu (moon)

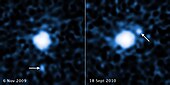

Gonggong and its moon Xiangliu, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2010 | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Gábor Marton Csaba Kiss Thomas Müller[a] |

| Discovery date | 18 September 2010 (first identified)[3][4] (announced 17 October 2016)[a] |

| Designations | |

| Gonggong I | |

| Pronunciation | /ʃæŋ.ljuː/ SHANG-LEW |

Named after | 相柳 Xiāngliǔ |

| S/2010 (225088) 1[5] | |

| Orbital characteristics[6] | |

| Epoch 8 December 2014 (JD 2457000.0) | |

| 24021±202 km (prograde), 24274±193 km (retrograde) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.2908±0.007 (prograde), 0.2828±0.0063 (retrograde) |

| 25.22073±0.000357 d (prograde), 25.22385±0.000362 d (retrograde) | |

| Inclination | 83.08°±0.86° (prograde), 119.14°±0.89° (retrograde) |

| 31.99°±1.07° (prograde), 104.09°±0.82° (retrograde) | |

| Satellite of | 225088 Gonggong |

| Physical characteristics | |

| <200 km[7] 40–100 km[6] | |

| >0.2[b] | |

| V–I=1.22±0.17[6] | |

| 6.93±0.15[6] | |

Xiangliu, full designation 225088 Gonggong I Xiangliu, is the only known moon of the scattered-disc dwarf planet Gonggong. It was discovered by a team of astronomers led by Csaba Kiss during an analysis of archival Hubble Space Telescope images of Gonggong. The discovery team had suspected that the slow rotation of Gonggong was caused by tidal forces exerted by an orbiting satellite.[3][2] Xiangliu was first identified in archival Hubble images taken with Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 on 18 September 2010.[8] Its discovery was reported and announced by Gábor Marton, Csaba Kiss, and Thomas Müller at the 48th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences on 17 October 2016.[3][1] The satellite is named after Xiangliu, a nine-headed venomous snake monster in Chinese mythology that attended the water god Gonggong as his chief minister.[9]

Observations

[edit]

Following the March 2016 discovery that Gonggong was an unusually slow rotator, the possibility was raised that a satellite may have slowed it down via tidal forces.[3] The indications of a possible satellite orbiting Gonggong led Csaba Kiss and his team to analyze archival Hubble observations of Gonggong.[8] Their analysis of Hubble images taken on 18 September 2010 revealed a faint satellite orbiting Gonggong at a distance of at least 15,000 km (9,300 mi).[1] The discovery was announced on 17 October 2016, though the satellite was not given a proper provisional designation.[4][11] The discovery team later also identified the satellite in earlier archival Hubble images taken on 9 November 2009.[8]

From follow-up Hubble observations in 2017, the absolute magnitude of the satellite is estimated to be at least 4.59 magnitudes dimmer than Gonggong, or 6.93±0.15 given Gonggong's estimated absolute magnitude of 2.34.[12][6]

Orbit

[edit]Based on Hubble images of Gonggong and Xiangliu taken in 2009 and 2010, the discovery team constrained Xiangliu's orbital period to between 20 and 100 days.[8] They better determined the orbit with additional Hubble observations in 2017.[12] Xiangliu is believed to be tidally locked to Gonggong.[6]

Because the observations of Xiangliu only span a small fraction of Gonggong's orbit around the Sun,[c] it is not yet possible to determine whether Xiangliu's orbit is prograde or retrograde.[6] Based on a prograde orbit model, Xiangliu orbits Gonggong at a distance of around 24,021 km (14,926 mi) and completes one orbit in 25.22 days.[d] Using the same prograde orbit model, the discovery team has estimated that its orbit is inclined to the ecliptic by about 83 degrees, implying that Gonggong is being viewed at a nearly pole-on configuration under the assumption that Xiangliu's orbit has a low inclination to Gonggong's equator.[6]

The orbit of Xiangliu is highly eccentric. The value of 0.29 is thought to have been caused by either an intrinsically eccentric orbit or by slow tidal evolution, in which the time for its orbit to circularize is comparable to the age of the Solar System.[6] It may have also resulted from the Kozai mechanism, driven by perturbations either from the Sun's tidal forces, or from higher order terms in the gravitational potential of Gonggong due to its oblate shape.[6] The orbital dynamics are thought to be similar to that of Quaoar's satellite, Weywot, which has a moderate eccentricity of about 0.14.[6]

Physical characteristics

[edit]The minimum possible diameter of Xiangliu, corresponding to an albedo of 1, is 36 km.[13] In order for Xiangliu's orbit to remain eccentric over a timescale comparable to the age of the Solar System, it must be less than 100 km (60 mi) in diameter, corresponding to an albedo greater than 0.2.[6][7][b] At discovery, the diameter of Xiangliu was initially estimated at 237 km (147 mi), under the assumption that the albedos of Xiangliu and Gonggong were equal.[8] Photometric measurements in 2017 showed that Xiangliu is far less red than Gonggong.[6] The color difference of ΔV–I=0.43±0.17 between Gonggong (V–I=1.65±0.03) and Xiangliu (V–I=1.22±0.17) is among the greatest among all known binary trans-Neptunian objects.[6] This large color difference is atypical for trans-Neptunian binary systems: the components of most trans-Neptunian binaries display little color variation.[6]

Name

[edit]The satellite is named after Xiangliu, the nine-headed venomous snake monster and minister of the water god Gonggong in Chinese mythology.[9] The eponymous Xiangliu is known for causing flooding and destruction.[14] When the discoverers of Gonggong proposed choices for a public vote on its name, they purposefully chose figures that had associates that could provide a name for the satellite.[15] Xiangliu's name was chosen by its discovery team led by Csaba Kiss, who had the privilege of naming the satellite.[16] The names of Gonggong and Xiangliu were approved by the International Astronomical Union's Committee on Small Body Nomenclature and were simultaneously announced by the Minor Planet Center on 5 February 2020.[17]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The discoverers of Xiangliu began their analysis of archival Hubble images in 2016. The satellite was first identified in Hubble images taken on 18 September 2010, and was later reported and announced by Gábor Marton, Csaba Kiss, and Thomas Müller in the 48th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences on 17 October 2016.[1][2][3]

- ^ a b The estimated maximum 100-km diameter corresponds to an albedo of 0.2.[6]

- ^ Less than 10 years, compared to Gonggong's orbital period of 554 years.

- ^ The values in the retrograde model are similar.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The moon of the large Kuiper-belt object 2007 OR10 (PDF). 48th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences. American Astronomical Society. 2016. 120.22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Moon orbits third largest dwarf planet in our solar system". Science Daily. 18 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Lakdawalla, Emily (19 October 2016). "DPS/EPSC update: 2007 OR10 has a moon!". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ a b Johnston, Wm. Robert (22 March 2020). "(225088) Gonggong and Xiangliu". Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 225088 Gonggong (2007 OR10)" (2021-10-24 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Kiss, Csaba; Marton, Gabor; Parker, Alex H.; Grundy, Will; Farkas-Takacs, Aniko; Stansberry, John; Pal, Andras; Muller, Thomas; Noll, Keith S.; Schwamb, Megan E.; Barr, Amy C.; Young, Leslie A.; Vinko, Jozsef (October 2018). "The mass and density of the dwarf planet (225088) 2007 OR10". Icarus. 334: 3–10. arXiv:1903.05439. Bibcode:2018DPS....5031102K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.03.013. S2CID 119370310. 311.02.

- ^ a b Arakawa, Sota; Hyodo, Ryuki; Shoji, Daigo; Genda, Hidenori (December 2021). "Tidal Evolution of the Eccentric Moon around Dwarf Planet (225088) Gonggong". The Astronomical Journal. 162 (6): 29. arXiv:2108.08553. Bibcode:2021AJ....162..226A. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac1f91. S2CID 237213381. 226.

- ^ a b c d e Kiss, Csaba; Marton, Gábor; Farkas-Takács, Anikó; Stansberry, John; Müller, Thomas; Vinkó, József; Balog, Zoltán; Ortiz, Jose-Luis; Pál, András (16 March 2017). "Discovery of a Satellite of the Large Trans-Neptunian Object (225088) 2007 OR10". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 838 (1): 5. arXiv:1703.01407. Bibcode:2017ApJ...838L...1K. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa6484. S2CID 46766640. L1.

- ^ a b "(225088) = Gonggong". Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Moon Around the Dwarf Planet 2007 OR10". spacetelescope.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ "Help Name 2007 OR10". Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ a b Parker, Alex (7 April 2017). "The Moons of Kuiper Belt Dwarf Planets Makemake and 2007 OR10 HST Proposal 15207". Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes. Space Telescope Science Institute. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Conversion of Absolute Magnitude to Diameter for Minor Planets". physics.sfasu.edu. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Yang, Lihui; An, Deming (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6.

- ^ "Astronomers Invite the Public to Help Name Kuiper Belt Object". International Astronomical Union. 10 April 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Schwamb, M. (29 May 2019). "The People Have Voted on 2007 OR10's Future Name!". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "M.P.C. 121135" (PDF). Minor Planet Circular. Minor Planet Center. 5 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2020.