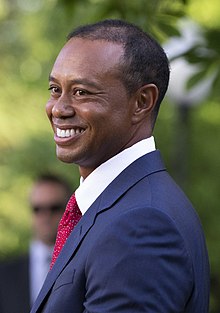

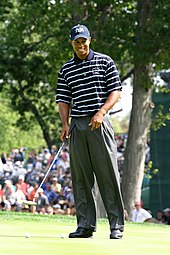

Tiger Woods

Eldrick Tont "Tiger" Woods (born December 30, 1975) is an American professional golfer. He is tied for first in PGA Tour wins, ranks second in men's major championships, and holds numerous golf records.[4] Woods is widely regarded as one of the greatest golfers of all time and is one of the most famous athletes in modern history.[4] He is an inductee of the World Golf Hall of Fame.[5]

Following an outstanding junior, college, and amateur golf career, Woods turned professional in 1996 at the age of 20. By the end of April 1997, he had won three PGA Tour events in addition to his first major, the 1997 Masters, which he won by 12 strokes in a record-breaking performance. He reached number one in the Official World Golf Ranking for the first time in June 1997, less than a year after turning pro. Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, Woods was the dominant force in golf. He was the top-ranked golfer in the world from August 1999 to September 2004 (264 consecutive weeks) and again from June 2005 to October 2010 (281 consecutive weeks). During this time, he won 13 of golf's major championships.

The next decade of Woods's career was marked by comebacks from personal problems and injuries. He took a self-imposed hiatus from professional golf from December 2009 to early April 2010 in an attempt to resolve marital issues with his wife at the time, Elin. Woods admitted to multiple marital infidelities, and the couple eventually divorced.[6] He fell to number 58 in the world rankings in November 2011 before ascending again to the number-one ranking between March 2013 and May 2014.[7][8] However, injuries led him to undergo four back surgeries between 2014 and 2017.[9] Woods competed in only one tournament between August 2015 and January 2018, and he dropped off the list of the world's top 1,000 golfers.[10][11] On his return to regular competition, Woods made steady progress to the top of the game, winning his first tournament in five years at the Tour Championship in September 2018 and his first major in 11 years at the 2019 Masters.

Woods has held numerous golf records. He has been the number one player in the world for the most consecutive weeks and for the greatest total number of weeks of any golfer in history. He has been awarded PGA Player of the Year a record 11 times[12] and has won the Byron Nelson Award for lowest adjusted scoring average a record eight times. Woods has the record of leading the money list in ten different seasons. He has won 15 professional major golf championships (trailing only Jack Nicklaus, who leads with 18) and 82 PGA Tour events (tied for first all time with Sam Snead).[13] Woods leads all active golfers in career major wins and career PGA Tour wins. Woods is the fifth (after Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus) player to achieve the career Grand Slam, and the youngest to do so. He is also the second golfer out of two (after Nicklaus) to achieve a career Grand Slam three times.[14]

Woods has won 18 World Golf Championships. He was also part of the American winning team for the 1999 Ryder Cup. In May 2019, Woods was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Trump, the fourth golfer to receive the honor.[15]

On February 23, 2021, Woods was hospitalized in serious but stable condition after a single-car collision and underwent emergency surgery to repair compound fractures sustained in his right leg in addition to a shattered ankle.[16] In an interview with Golf Digest in November 2021, Woods indicated that his full-time career as a professional golfer was over, although he would continue to play "a few events per year".[17] For the first time since the car crash, he returned to the PGA Tour at the 2022 Masters.

Background and family

Woods was born on December 30, 1975, in Cypress, California,[18] to Earl[19] and Kultida "Tida" Woods.[20] He is their only child, though he has two half-brothers and a half-sister from his father's first marriage.[21] Earl was a retired U.S. Army officer and Vietnam War veteran. Earl was born to African-American parents and was also said to have had European and Native American descent.[22][23] Kultida (née Punsawad) is originally from Thailand, where Earl met her when he was on a tour of duty there in 1968. She is of mixed Thai, Chinese, and Dutch ancestry.[24] In 2002, ESPN claimed: "For the record, he is one-quarter Thai, one-quarter Chinese, one-quarter Caucasian, one-eighth African American and one-eighth Native American."[25] Tiger has described his ethnic make-up as "Cablinasian" (a syllabic abbreviation he coined from Caucasian, Black, American Indian, and Asian).[26]

Woods's first name, Eldrick, was chosen by his mother because it began with "E" (for Earl) and ended with "K" (for Kultida). His middle name Tont is a traditional Thai name. He was nicknamed Tiger in honor of his father's friend, South Vietnamese Colonel Vuong Dang Phong, who had also been known as Tiger.[27] Woods has a niece, Cheyenne Woods, who played for the Wake Forest University golf team and turned professional in 2012 when she made her pro debut in the LPGA Championship.[28]

Early life and amateur golf career

Woods grew up in Orange County, California. He was a child prodigy who was introduced to golf before the age of two by his athletic father Earl Woods. Earl was a single-digit handicap amateur golfer who also was one of the earliest African-American college baseball players at Kansas State University.[29] Woods told reporters he had wanted to be a baseball player like his father but abandoned that goal after tearing his rotator cuff.[30] His father was a member of the military and had playing privileges at the Navy golf course beside the Joint Forces Training Base in Los Alamitos, which allowed Tiger to play there. Tiger also played at the par 3 Heartwell golf course in Long Beach, as well as some of the municipals in Long Beach.[31]

In 1978, Woods putted against comedian Bob Hope in a television appearance on The Mike Douglas Show. At age three, he shot a 48 over nine holes at the Navy course. At age five, he appeared in Golf Digest and on ABC's That's Incredible![32] Before turning seven, Woods won the Under Age 10 section of the Drive, Pitch, and Putt competition, held at the Navy Golf Course in Cypress.[33] In 1984 at the age of eight, he won the 9–10 boys' event, the youngest age group available, at the Junior World Golf Championships.[34] He first broke 80 at age eight.[35] He went on to win the Junior World Championships six times, including four consecutive wins from 1988 to 1991.[36][37][38][39][40] Woods's father Earl wrote that Tiger first defeated him at the age of 11 years, with Earl trying his best. He lost to Woods every time from then on.[41] Woods first broke 70 on a regulation golf course at age 12.[42]

When Woods was 13 years old, he played in the 1989 Big I, which was his first major national junior tournament. In the final round, he was paired with pro John Daly, who was then relatively unknown. The event's format placed a professional with each group of juniors who had qualified. Daly birdied three of the last four holes to beat him by only one stroke.[43] As a young teenager, Woods first met Jack Nicklaus in Los Angeles at the Bel-Air Country Club, when Nicklaus was performing a clinic for the club's members. Woods was part of the show, and he impressed Nicklaus and the crowd with his skills and potential.[44] Earl Woods had researched in detail the career accomplishments of Nicklaus and had set his young son the goals of breaking those records.[42]

Woods was 15 years old and a student at Western High School in Anaheim when he became the youngest U.S. Junior Amateur champion; this was a record that stood until it was broken by Jim Liu in 2010.[45] He was named 1991's Southern California Amateur Player of the Year (for the second consecutive year) and Golf Digest Junior Amateur Player of the Year. In 1992, he defended his title at the U.S. Junior Amateur Championship, becoming the tournament's first two-time winner. He also competed in his first PGA Tour event, the Nissan Los Angeles Open (he missed the 36-hole cut), and was named Golf Digest Amateur Player of the Year, Golf World Player of the Year, and Golfweek National Amateur of the Year.[46][47]

The following year, Woods won his third consecutive U.S. Junior Amateur; he remains the event's only three-time winner.[48] In 1994, at the TPC at Sawgrass in Florida, he became the youngest winner of the U.S. Amateur, a record he held until 2008 when it was broken by Danny Lee.[49][50] He was a member of the American team at the 1994 Eisenhower Trophy World Amateur Golf Team Championships (winning), and the 1995 Walker Cup (losing).[51][52]

Woods graduated from Western High School at age 18 in 1994 and was voted "Most Likely to Succeed" among the graduating class. He starred for the high school's golf team under coach Don Crosby.[53] Woods learned to manage his stuttering as a boy.[54] This was not widely known until he wrote a letter to a boy who contemplated suicide. Woods wrote, "I know what it's like to be different and to sometimes not fit in. I also stuttered as a child and I would talk to my dog and he would sit there and listen until he fell asleep. I also took a class for two years to help me, and I finally learned to stop."[55]

College golf career

Woods was heavily recruited by college golf powers. He chose Stanford University, the 1994 NCAA champions. He enrolled at Stanford in the fall of 1994 under a golf scholarship and won his first collegiate event, the 40th Annual William H. Tucker Invitational, that September.[56] He selected a major in economics and was nicknamed "Urkel" by college teammate Notah Begay III.[57] In 1995, he successfully defended his U.S. Amateur title at the Newport Country Club in Rhode Island[49] and was voted Pac-10 Player of the Year, NCAA First Team All-American, and Stanford's Male Freshman of the Year (an award that encompasses all sports).[58][59]

At age 19, Woods participated in his first PGA Tour major, the 1995 Masters, and tied for 41st as the only amateur to make the cut. At age 20 in 1996, he became the first golfer to win three consecutive U.S. Amateur titles[60] and won the NCAA individual golf championship.[61] In winning the silver medal as leading amateur at The Open Championship, he tied the record for an amateur aggregate score of 281.[62] He left college after two years in order to turn professional in the golf industry. In 1996, Woods moved out of California, stating in 2013 that it was due to the state's high tax rate.[63]

Professional career

Woods turned professional at age 20 in August 1996 and immediately signed advertising deals with Nike, Inc. and Titleist that ranked as the most lucrative endorsement contracts in golf history at that time.[64][65] Woods was named Sports Illustrated's 1996 Sportsman of the Year and PGA Tour Rookie of the Year.[66] On April 13, 1997, he won his first major, the Masters, in record-breaking fashion and became the tournament's youngest winner at age 21.[67] Two months later, he set the record for the fastest ascent to No. 1 in the Official World Golf Ranking.[68] After a lackluster 1998, Woods finished the 1999 season with eight wins, including the PGA Championship, a feat not achieved since Johnny Miller did it in 1974.[69][70]

Woods was severely myopic; his eyesight had a rating of 11 diopters. In order to correct this problem, he underwent successful laser eye surgery in 1999,[71] and he immediately resumed winning tour events. In 2007, his vision again began to deteriorate, and he underwent laser eye surgery a second time.[72] In 2000, Woods won six consecutive events on the PGA Tour, which was the longest winning streak since Ben Hogan did it in 1948. One of these was the U.S. Open, where he broke or tied nine tournament records in what Sports Illustrated called "the greatest performance in golf history", in which Woods won the tournament by a record 15-stroke margin and earned a check for $800,000.[73] At age 24, he became the youngest golfer to achieve the Career Grand Slam.[74] At the end of 2000, Woods had won nine of the twenty PGA Tour events he entered and had broken the record for lowest scoring average in tour history. He was named the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year, the only athlete to be honored twice, and was ranked by Golf Digest magazine as the twelfth-best golfer of all time.[75]

When Woods won the 2001 Masters, he became the only player to win four consecutive major professional golf titles, although not in the same calendar year. This achievement came to be known as the "Tiger Slam".[76] Following a stellar 2001 and 2002 in which he continued to dominate the tour, Woods's career hit a slump.[69][77] He did not win a major in 2003 or 2004. In September 2004, Vijay Singh overtook Woods in the Official World Golf Rankings, ending Woods's record streak of 264 weeks at No. 1.[78]

Woods rebounded in 2005, winning six PGA Tour events and reclaiming the top spot in July after swapping it back and forth with Singh over the first half of the year.[79]

Woods began dominantly in 2006, winning his first two PGA tournaments but failing to capture his fifth Masters championship in April.[80] Following the death of his father in May, Woods took some time off from the tour and appeared rusty upon his return at the U.S. Open at Winged Foot Golf Club, where he missed the cut.[81] However, he quickly returned to form and ended the year by winning six consecutive tour events. At the season's close, Woods had 54 total wins that included 12 majors; he broke the tour records for both total wins and total majors wins over eleven seasons.[82]

Woods continued to excel in 2007 and the first part of 2008. In April 2008, he underwent knee surgery and missed the next two months on the tour.[83] Woods returned for the 2008 U.S. Open, where he struggled the first day but ultimately claimed a dramatic sudden death victory over Rocco Mediate that followed an 18-hole playoff, after which Mediate said, "This guy does things that are just not normal by any stretch of the imagination," and Kenny Perry added, "He beat everybody on one leg."[84] Two days later, Woods announced that he would miss the remainder of the season due to additional knee surgery, and that his knee was more severely damaged than previously revealed, prompting even greater praise for his U.S. Open performance. Woods called it "my greatest ever championship."[85] In Woods's absence, television ratings for the remainder of the season suffered a huge decline from 2007.[86]

Woods had a much anticipated return to golf in 2009, when he performed well. His comeback included a spectacular performance at the 2009 Presidents Cup, but he failed to win a major, the first year since 2004 that he did not do so.[87] After his marital infidelities came to light and received massive media coverage at the end of 2009 (see further details below), Woods announced in December that he would be taking an indefinite break from competitive golf.[6] In February 2010, he delivered a televised apology for his behavior, saying "I was wrong and I was foolish."[88] During this period, several companies ended their endorsement deals with Woods.[89]

Woods returned to competition in April at the 2010 Masters, where he finished tied for fourth place.[90] He followed the Masters with poor showings at the Quail Hollow Championship and the Players Championship, where he withdrew in the fourth round, citing injury.[91] Shortly afterward, Hank Haney, Woods's coach since 2003, resigned the position. In August, Woods hired Sean Foley as Haney's replacement. The rest of the season went badly for Woods, who failed to win a single event for the first time since turning professional, while nevertheless finishing the season ranked No. 2 in the world.

In 2011, Woods's performance continued to suffer; this took its toll on his ranking. After falling to No. 7 in March, he rebounded to No. 5 with a strong showing at the 2011 Masters, where he tied for fourth place.[92] Due to leg injuries incurred at the Masters, he missed several summer stops on the PGA Tour. In July, he fired his longtime caddie Steve Williams (who was shocked by the dismissal), and replaced him on an interim basis with friend Bryon Bell until he hired Joe LaCava.[93] After returning to tournament play in August, Woods continued to falter, and his ranking gradually fell to a low of #58.[8] He rose to No. 50 in mid-November after a third-place finish at the Emirates Australian Open, and broke his winless streak with a victory at December's Chevron World Challenge.[8][94][95]

Woods began his 2012 season with two tournaments (the Abu Dhabi HSBC Golf Championship and the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am) where he started off well but struggled on the final rounds. Following the WGC-Accenture Match Play Championship, where he was knocked out in the second round by missing a 5-foot putt,[96] Woods revised his putting technique and tied for second at The Honda Classic, with the lowest final-round score in his PGA Tour career. After a short time off due to another leg injury, Woods won the Arnold Palmer Invitational, his first win on the PGA Tour since the BMW Championship in September 2009. Following several dismal performances, Woods notched his 73rd PGA Tour win at the Memorial Tournament in June, tying Jack Nicklaus in second place for most PGA Tour victories;[97] a month later, Woods surpassed Nicklaus with a win at the AT&T National, to trail only Sam Snead, who accumulated 82 PGA tour wins.[98]

The year 2013 brought a return of Woods's dominating play. In January, he won the Farmers Insurance Open by four shots for his 75th PGA Tour win. It was the seventh time he won the event.[99] In March, he won the WGC-Cadillac Championship, also for the seventh time, giving him his 17th WGC title and first since 2009.[100] Two weeks later, he won the Arnold Palmer Invitational, winning the event for a record-tying 8th time. The win moved him back to the top of the world rankings.[101] To commemorate that achievement, Nike was quick to launch an ad with the tagline "winning takes care of everything".[102]

During the 2013 Masters, Woods faced disqualification after unwittingly admitting in a post-round interview with ESPN that he took an illegal drop on the par-5 15th hole when his third shot bounced off the pin and into the water. After further review of television footage, Woods was assessed a two-stroke penalty for the drop but was not disqualified.[103] He finished tied for fourth in the event. Woods won The Players Championship in May 2013, his second career win at the event, notching his fourth win of the 2013 season. It was the quickest he got to four wins in any season of his professional career.

Woods had a poor showing at the 2013 U.S. Open as a result of an elbow injury that he sustained at The Players Championship. In finishing at 13-over-par, he recorded his worst score as a professional and finished 12 strokes behind winner Justin Rose. After a prolonged break because of the injury, during which he missed the Greenbrier Classic and his own AT&T National, he returned at the Open Championship at Muirfield. Despite being in contention all week and beginning the final round only two strokes behind Lee Westwood, he struggled with the speed of the greens and could only manage a 3-over-par 74 that left him tied for 6th place, five strokes behind eventual winner Phil Mickelson. Two weeks later, Woods returned to form at the WGC-Bridgestone Invitational, recording his 5th win of the season and 8th win at the event in its 15-year history. His second-round 61 matched his record score on the PGA Tour and could easily have been a 59 were it not for some short missed birdie putts on the closing holes. This gave him a seven-stroke lead that he held onto for the rest of the tournament. But at the PGA Championship at Oak Hill Country Club, Woods never was in contention, making 2013 his fifth full season where he did not win a major; he was in contention in only two of the four majors in 2013.

After a slow start to 2014, Woods sustained an injury during the final round of The Honda Classic and was unable to finish the tournament. He withdrew after the 13th hole, citing back pain.[104] He subsequently competed in the WGC-Cadillac Championship but was visibly in pain during much of the last round. He was forced to skip the Arnold Palmer Invitational at the end of March 2014,[105] and after undergoing back surgery, he announced on April 1 that he would miss the Masters for the first time since 1994.[106] Woods returned at the Quicken Loans National in June, however he said that his expectations for the week were low. He struggled with nearly every aspect of his game and missed the cut. He next played at The Open Championship, contested at Hoylake, where Woods had won eight years prior. Woods fired a brilliant 69 in the first round to put himself in contention, but shot 77 on Friday and eventually finished 69th. Despite his back pain, he played at the 2014 PGA Championship where he failed to make the cut. On August 25, 2014, Woods and his swing coach Sean Foley parted ways. In the four years under Foley, he won eight times but no majors. He had previously won eight majors with Harmon and six with Haney. Woods said there was currently no timetable to find a replacement swing coach.[107]

On February 5, 2015, Woods withdrew from the Farmers Insurance Open after another back injury.[108] Woods stated on his website that it was unrelated to his previous surgery and he would take a break from golf until his back healed.[109] He returned for the Masters, finishing in a tie for 17th. In the final round, Woods injured his wrist after his club hit a tree root. He later stated that a bone popped out of his wrist, but he adjusted it back into place and finished the round.[110] Woods then missed the cut at the 2015 U.S. Open and Open Championship, the first time Woods missed the cut at consecutive majors, finishing near the bottom of the leaderboard both times.[111] He finished tied for 18th at the Quicken Loans National on August 2.[112] In late August 2015, Woods played quite well at the Wyndham Championship finishing the tournament at 13-under, only four strokes behind the winner, and tied for 10th place.[113] Woods offered only a brief comment on the speculation that he was still recovering from back surgery, saying it was "just my hip" but offering no specifics.[114]

Woods had back surgery on September 16, 2015. In late March 2016, he announced that he would miss the Masters while he recovered from the surgery;[115] he had also missed the 2014 Masters due to a back problem.[116] "I'm absolutely making progress, and I'm really happy with how far I've come," he explained in a statement. "But I still have no timetable to return to competitive golf."[117] However, he did attend the Masters Champions Dinner on April 5, 2016.[118] For the first time in his career, he missed all four majors in one year due to problems with his back. In October 2016, he told Charlie Rose on PBS that he still wanted to break Jack Nicklaus's record of 18 major titles.[119] Woods underwent back surgery in December 2016 and spent the next 15 months off the Tour. He made his return to competitive golf in the Hero World Challenge.[120]

Woods's back problems continued to hinder him in 2017. He missed the cut at the Farmers Insurance Open in January and pulled out of a European Tour event in Dubai on February 3. On March 31, Woods announced on his website that he would not be playing in the 2017 Masters Tournament despite being cleared to play by his doctors. Woods said that although he was happy with his rehabilitation, he did not feel "tournament ready."[121][122] Woods subsequently told friends, "I'm done".[123] On April 20, Woods announced that he had undergone his fourth back surgery since 2014 to alleviate back and leg pain. Recovery time required up to six months, meaning that Woods would spend the rest of the year without playing any professional golf.[124] Woods returned to competitive golf at the Hero World Challenge in the Bahamas. He shot rounds of 69–68–75–68 and finished tied for 9th place. His world ranking went from 1,199th to 668th, which was the biggest jump in the world rankings in his career.

On March 11, 2018, he finished one-shot back and tied for second at the Valspar Championship in Florida, his first top-five finish on the PGA Tour since 2013.[125] He then tied for sixth with a score of five under par at the 2018 Open Championship.[126] At the last major of the year, the 2018 PGA Championship, Woods finished second, two shots behind the winner Brooks Koepka. It was his best result in a major since 2009 (second at the 2009 PGA Championship) and moved him up to 26th in the world rankings. His final round of 64 was his best-ever final round in a major.[127][11]

Woods returned to the winner's circle for the 80th time in his PGA Tour career on September 23, 2018, when he won the season-ending Tour Championship at East Lake Golf Club for the second time and that tournament for the third time. He shot rounds of 65–68–65–71 to win by two strokes over Billy Horschel.[128]

On April 14, 2019, Woods won the Masters, which was his first major championship win in eleven years and his 15th major overall. He finished 13 under par to win by one stroke over Dustin Johnson, Xander Schauffele and Brooks Koepka.[129] At age 43, he became the second oldest golfer ever to win the Masters, after Jack Nicklaus who was 46 when he triumphed in 1986.[130] In August 2019, Woods announced via social media that he underwent knee surgery to repair minor cartilage damage and that he had an arthroscopic procedure during the Tour Championship. In his statement, Woods also confirmed that he was walking and intends on traveling and playing in Japan in October.[131]

Woods played in his first 2020 PGA Tour event at the Zozo Championship in October 2019, which was the first-ever PGA Tour event played in Japan. Woods, who played a highly publicized skins game earlier in the week at the same course as the Championship, held at least a share of the lead after every round of the rain-delayed tournament, giving him a three stroke victory over Hideki Matsuyama.[132] The win was Woods's 82nd on Tour, tying him with Sam Snead for the most victories all time on the PGA Tour.[133][134]

In December 2020, Woods had microdiscectomy surgery on his back for the fifth time.[135] The operation was to remove a pressurized disc fragment that was pinching his nerve and causing him pain during the PNC Championship. Woods returned to play in his first professional tournament since his 2021 motor vehicle crash at the 2022 Masters Tournament. He made the cut and finished in 47th place at 13-over par, 23 shots behind the winner Scottie Scheffler.[136]

In August 2022, Woods, Rory McIlroy, Mike McCarley, and the PGA Tour announced the formation of TGL, a six-team virtual golfing league.[137] In November 2023, Woods revealed himself as an co-owner and player for Jupiter Links Golf Club, founded with investments by David Blitzer.[138]

Honors

On August 20, 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and his wife Maria Shriver announced that Woods would be inducted into the California Hall of Fame. He was inducted December 5, 2007 at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts in Sacramento.[139] In May 2019, following his 2019 Masters Tournament win, Woods was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Donald Trump.[140]

In 2000 and 2001, Woods was named the Laureus World Sportsman of the Year, becoming the inaugural recipient of the award.[141] In 2000 he received the BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year, an award given to a non-British sportsperson considered to have made the most substantial contribution to a sport.[142] Domestically, Woods has also been recognized by U.S. publications. He was named Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year a record-tying four times, was named "Athlete of the Decade" by the Associated Press in 2009, and is one of only two people to be named Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year more than once.[143][144]

Since his record-breaking win at the 1997 Masters, Woods has been the biggest name in golf and his presence in tournaments has drawn a huge fan following. Some sources have credited him for dramatically increasing prize money in golf, generating interest in new PGA tournament audiences, and for drawing the largest TV ratings in golf history.[66][145] His recognition as one of the most famous athletes in modern history includes being depicted in a wax sculpture at Madame Tussauds.[146]

Endorsements

During the first decade of his professional career, Woods was the world's most marketable athlete.[147] Shortly after his 21st birthday in 1996, he signed endorsement deals with numerous companies, including General Motors, Titleist, General Mills, American Express, Accenture, and Nike. In 2000, he signed a 5-year, $105 million contract extension with Nike, which was the largest endorsement package signed by a professional athlete at that time.[148] Woods's endorsement has been credited with playing a significant role in taking the Nike Golf brand from a "start-up" golf company earlier in the previous decade to becoming the leading golf apparel company in the world and a major player in the equipment and golf ball market.[147][149] Nike Golf is one of the fastest growing brands in the sport, with an estimated $600 million in sales.[150] Woods has been described as the "ultimate endorser" for Nike Golf,[150] frequently seen wearing Nike gear during tournaments, and even in advertisements for other products.[148] Woods receives a percentage from the sales of Nike Golf apparel, footwear, golf equipment, golf balls,[147] and has a building named after him at Nike's headquarters campus in Beaverton, Oregon.[151]

In 2002, Woods was involved in every aspect of the launch of Buick's Rendezvous SUV. A company spokesman stated that Buick was happy with the value of Woods's endorsement, pointing out that more than 130,000 Rendezvous vehicles were sold in 2002 and 2003. "That exceeded our forecasts," he was quoted as saying, "It has to be in recognition of Tiger." In February 2004, Buick renewed Woods's endorsement contract for another five years, in a deal reportedly worth $40 million.[148]

Woods collaborated closely with TAG Heuer to develop the world's first professional golf watch, which was released in April 2005.[152] The lightweight, titanium-construction watch, incorporates features to facilitate wearing the watch while playing the game. It is capable of absorbing up to 5,000 Gs of shock, far in excess of the forces generated by a normal golf swing.[152] In 2006, the TAG Heuer Professional Golf Watch won the prestigious iF product design award in the Leisure/Lifestyle category.[153]

Woods also endorsed the Tiger Woods PGA Tour series of video games; he has done so since 1999.[154] In 2006, he signed a six-year contract with Electronic Arts, the series' publisher.[155]

In February 2007, Woods, Roger Federer, and Thierry Henry became ambassadors for the "Gillette Champions" marketing campaign. Gillette did not disclose financial terms, though an expert estimated the deal could total between $10 million and $20 million.[156]

In October 2007, Gatorade announced that Woods would have his own brand of sports drink starting in March 2008. "Gatorade Tiger" was his first U.S. deal with a beverage company and his first licensing agreement. Although no figures were officially disclosed, Golfweek magazine reported that it was for five years and could pay him as much as $100 million.[157] The company decided in early fall 2009 to discontinue the drink due to weak sales.[158]

In October 2012, it was announced that Woods signed an exclusive endorsement deal with Fuse Science, Inc, a sports nutrition firm.[159]

In 1997, Woods and fellow golfer Arnold Palmer initiated a civil case against Bruce Matthews (the owner of Gotta Have It Golf, Inc.) and others in the effort to stop the unauthorized sale of their images and alleged signatures in the memorabilia market. Matthews and associated parties counterclaimed that Woods and his company, ETW Corporation, committed several acts including breach of contract, breach of implied duty of good faith, and violations of Florida's Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act.[160] Palmer also was named in the counter-suit, accused of violating the same licensing agreement in conjunction with his company Arnold Palmer Enterprises.

On March 12, 2014, a Florida jury found in favor of Gotta Have It on its breach of contract and other related claims, rejected ETW's counterclaims, and awarded Gotta Have It $668,346 in damages.[161] The award may end up exceeding $1 million once interest has been factored in, though the ruling may be appealed.

In August 2016, Woods announced that he would be seeking a new golf equipment partner[162] after the news of Nike's exit from the equipment industry.[163] It was announced on January 25, 2017, that he would be signing a new club deal with TaylorMade.[164] He added the 2016 M2 driver along with the 2017 M1 fairway woods, with irons to be custom made at a later date. He also added his Scotty Cameron Newport 2 GSS, a club he used to win 13 of his 15 majors.[165] Also, in late 2016, he would add Monster Energy as his primary bag sponsor, replacing MusclePharm.[166]

On January 8, 2024, Woods announced that he would be parting ways with Nike after 27 years, ending one of the most lucrative endorsements any athlete has had.[167]

Accumulated wealth

Woods has appeared on Forbes list of the world's highest-paid athletes.[168][169] According to Golf Digest, Woods earned $769,440,709 from 1996 to 2007,[170] and the magazine predicted that Woods would pass a billion dollars in earnings by 2010.[171] In 2009, Forbes confirmed that Woods was indeed the world's first professional athlete to earn over a billion dollars in his career, after accounting for the $10 million bonus Woods received for the FedEx Cup title.[172] The same year, Forbes estimated his net worth to be $600 million, making him the second richest person of color in the United States, behind only Oprah Winfrey.[173] In 2015, Woods ranked ninth in Forbes list of the world's highest-paid athletes, being the top among Asian Americans or the fourth among African Americans.[174] As of 2017, Woods was considered to be the highest-paid golfer in the world.[175] In 2022, Woods was the first golfer to have a net worth over one billion dollars.[176]

Tiger-proofing

Early in Woods's career, a small number of golf industry analysts expressed concern about his impact on the competitiveness of the game and the public appeal of professional golf. Sportswriter Bill Lyon of Knight Ridder asked in a column, "Isn't Tiger Woods actually bad for golf?" (though Lyon ultimately concluded that he was not).[177] At first, some pundits feared that Woods would drive the spirit of competition out of the game of golf by making existing courses obsolete and relegating opponents to simply competing for second place each week.

A related effect was measured by University of California economist Jennifer Brown, who found that other golfers scored worse when competing against Woods than when he was not in the tournament. The scores of highly skilled golfers are nearly one stroke higher when playing against Woods. This effect was larger when he was on winning streaks and disappeared during his well-publicized slump in 2003–04. Brown explains the results by noting that competitors of similar skill can hope to win by increasing their level of effort, but that, when facing a "superstar" competitor, extra exertion does not significantly raise one's level of winning while increasing risk of injury or exhaustion, leading to reduced effort.[178] Many courses in the PGA Tour rotation (including major championship sites like Augusta National) have added yardage to their tees in an effort to reduce the advantage of long hitters like Woods, in a strategy that became known as "Tiger-proofing".[179] Woods said he welcomed the change, in that adding yardage to courses did not affect his ability to win.[180]

Career achievements

Woods has won 82 official PGA Tour events, including 15 majors. He is 14–1 when going into the final round of a major with at least a share of the lead. Multiple golf experts have heralded Woods as "the greatest closer in history".[181] He has the lowest career scoring average and the largest career earnings of any player in PGA Tour history.

Woods's victory at the 2013 Players Championship also marked a win in his 300th PGA Tour start.[182] He also won golf tournaments in his 100th (in 2000) and 200th (in 2006) tour starts.[183]

Woods has spent the most consecutive and cumulative weeks atop the world rankings. He is one of five players (along with Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player, and Jack Nicklaus) to have won all four major championships in his career, known as the Career Grand Slam, and was the youngest to do so.[184] Woods is the only player to have consecutively won all four major championships open to professionals, accomplishing the feat in the 2000–2001 seasons.

- PGA Tour wins (82)

- European Tour wins (41)

- Japan Golf Tour wins (3)

- Asian PGA Tour wins (2)

- PGA Tour of Australasia wins (3)

- Other wins (17)

- Amateur wins (21)

Major championships

Wins (15)

| Year | Championship | 54 holes | Winning score | Margin | Runner(s)-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Masters Tournament | 9 shot lead | −18 (70-66-65-69=270) | 12 strokes | |

| 1999 | PGA Championship | Tied for lead | −11 (70-67-68-72=277) | 1 stroke | |

| 2000 | U.S. Open | 10 shot lead | −12 (65-69-71-67=272) | 15 strokes | |

| 2000 | The Open Championship | 6 shot lead | −19 (67-66-67-69=269) | 8 strokes | |

| 2000 | PGA Championship (2) | 1 shot lead | −18 (66-67-70-67=270) | Playoff1 | |

| 2001 | Masters Tournament (2) | 1 shot lead | −16 (70-66-68-68=272) | 2 strokes | |

| 2002 | Masters Tournament (3) | Tied for lead | −12 (70-69-66-71=276) | 3 strokes | |

| 2002 | U.S. Open (2) | 4 shot lead | −3 (67-68-70-72=277) | 3 strokes | |

| 2005 | Masters Tournament (4) | 3 shot lead | −12 (74-66-65-71=276) | Playoff2 | |

| 2005 | The Open Championship (2) | 2 shot lead | −14 (66-67-71-70=274) | 5 strokes | |

| 2006 | The Open Championship (3) | 1 shot lead | −18 (67-65-71-67=270) | 2 strokes | |

| 2006 | PGA Championship (3) | Tied for lead | −18 (69-68-65-68=270) | 5 strokes | |

| 2007 | PGA Championship (4) | 3 shot lead | −8 (71-63-69-69=272) | 2 strokes | |

| 2008 | U.S. Open (3) | 1 shot lead | −1 (72-68-70-73=283) | Playoff3 | |

| 2019 | Masters Tournament (5) | 2 shot deficit | −13 (70-68-67-70=275) | 1 stroke |

1Defeated May in three-hole playoff by 1 stroke: Woods (3–4–5=12), May (4–4–5=13)

2Defeated DiMarco in a sudden-death playoff: Woods (3), DiMarco (4).

3Defeated Mediate with a par on 1st sudden death hole after 18-hole playoff was tied at even par. This was the final time an 18-hole playoff was used in competition.

Results timeline

Results not in chronological order in 2020.

| Tournament | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | T41LA | CUT | 1 | T8 | T18 |

| U.S. Open | WD | T82 | T19 | T18 | T3 |

| The Open Championship | T68 | T22LA | T24 | 3 | T7 |

| PGA Championship | T29 | T10 | 1 |

| Tournament | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | 5 | 1 | 1 | T15 | T22 | 1 | T3 | T2 | 2 | T6 |

| U.S. Open | 1 | T12 | 1 | T20 | T17 | 2 | CUT | T2 | 1 | T6 |

| The Open Championship | 1 | T25 | T28 | T4 | T9 | 1 | 1 | T12 | CUT | |

| PGA Championship | 1 | T29 | 2 | T39 | T24 | T4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Tournament | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | T4 | T4 | T40 | T4 | T17 | T32 | |||

| U.S. Open | T4 | T21 | T32 | CUT | CUT | ||||

| The Open Championship | T23 | T3 | T6 | 69 | CUT | T6 | |||

| PGA Championship | T28 | CUT | T11 | T40 | CUT | CUT | 2 |

| Tournament | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | 1 | T38 | 47 | WD | 60 | |

| PGA Championship | CUT | T37 | WD | CUT | ||

| U.S. Open | T21 | CUT | CUT | |||

| The Open Championship | CUT | NT | CUT | CUT |

LA = low amateur

CUT = missed the half-way cut

WD = withdrew

"T" indicates a tie for a place.

NT = no tournament due to COVID-19 pandemic

Summary

| Tournament | Wins | 2nd | 3rd | Top-5 | Top-10 | Top-25 | Events | Cuts made |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masters Tournament | 5 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 26 | 25 |

| PGA Championship | 4 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 23 | 18 |

| U.S. Open | 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 17 |

| The Open Championship | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 15 | 23 | 18 |

| Totals | 15 | 7 | 4 | 33 | 41 | 59 | 95 | 78 |

- Most consecutive cuts made – 39 (1996 U.S. Open – 2006 Masters)

- Longest streak of top-10s – 8 (1999 U.S. Open – 2001 Masters)

The Players Championship

Wins (2)

| Year | Championship | 54 holes | Winning score | Margin | Runner(s)-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | The Players Championship | 2 shot deficit | −14 (72-69-66-67=274) | 1 stroke | |

| 2013 | The Players Championship (2) | Tied for lead | −13 (67-67-71-70=275) | 2 strokes |

Results timeline

| Tournament | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Players Championship | T31 | T35 | T10 | 2 | 1 | T14 | T11 | T16 | T53 | T22 | T37 | 8 |

| Tournament | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Players Championship | WD | WD | T40 | 1 | T69 | T11 | T30 |

WD = withdrew

"T" indicates a tie for a place.

World Golf Championships

Wins (18)

| Year | Championship | 54 holes | Winning score | Margin | Runner(s)-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | WGC-NEC Invitational | 5 shot lead | −10 (66-71-62-71=270) | 1 stroke | |

| 1999 | WGC-American Express Championship | 1 shot deficit | −6 (71-69-70-68=278) | Playoff | |

| 2000 | WGC-NEC Invitational (2) | 9 shot lead | −21 (64-61-67-67=259) | 11 strokes | |

| 2001 | WGC-NEC Invitational (3) | 2 shot deficit | −12 (66-67-66-69=268) | Playoff | |

| 2002 | WGC-American Express Championship (2) | 5 shot lead | −25 (65-65-67-66=263) | 1 stroke | |

| 2003 | WGC-Accenture Match Play Championship | n/a | 2 and 1 | ||

| 2003 | WGC-American Express Championship (3) | 2 shot lead | −6 (67-66-69-72=274) | 2 strokes | |

| 2004 | WGC-Accenture Match Play Championship (2) | n/a | 3 and 2 | ||

| 2005 | WGC-NEC Invitational (4) | Tied for lead | −6 (66-70-67-71=274) | 1 stroke | |

| 2005 | WGC-American Express Championship (4) | 2 shot deficit | −10 (67-68-68-67=270) | Playoff | |

| 2006 | WGC-Bridgestone Invitational (5) | 1 shot deficit | −10 (67-64-71-68=270) | Playoff | |

| 2006 | WGC-American Express Championship (5) | 6 shot lead | −23 (63-64-67-67=261) | 8 strokes | |

| 2007 | WGC-CA Championship (6) | 4 shot lead | −10 (71-66-68-73=278) | 2 strokes | |

| 2007 | WGC-Bridgestone Invitational (6) | 1 shot deficit | −8 (68-70-69-65=272) | 8 strokes | |

| 2008 | WGC-Accenture Match Play Championship (3) | n/a | 8 and 7 | ||

| 2009 | WGC-Bridgestone Invitational (7) | 3 shot deficit | −12 (68-70-65-65=268) | 4 strokes | |

| 2013 | WGC-Cadillac Championship (7) | 4 shot lead | −19 (66-65-67-71=269) | 2 strokes | |

| 2013 | WGC-Bridgestone Invitational (8) | 7 shot lead | −15 (66-61-68-70=265) | 7 strokes | |

Results timeline

Results not in chronological order before 2015.

| Tournament | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Championship | 1 | T5 | NT1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | T9 | T10 | WD | 1 | T25 | T10 | |||||

| Match Play | QF | 2 | R64 | 1 | 1 | R32 | R16 | R16 | 1 | R32 | R64 | R32 | R64 | QF | |||||||

| Invitational | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | T4 | T2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | T78 | T37 | T8 | 1 | WD | T31 | |||||

| Champions | T6 | T6 | |||||||||||||||||||

1Cancelled due to 9/11

QF, R16, R32, R64 = Round in which player lost in match play

WD = withdrew

NT = No tournament

"T" = tied

Note that the HSBC Champions did not become a WGC event until 2009.

PGA Tour career summary

| Season | Starts | Cuts made |

Wins (majors) | 2nd | 3rd | Top 10 |

Top 25 |

Earnings ($) |

Money list rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 1993 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 1994 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 1995 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| 1996 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 790,594 | 24 |

| 1997 | 21 | 20 | 4 (1) | 1 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 2,066,833 | 1 |

| 1998 | 20 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 17 | 1,841,117 | 4 |

| 1999 | 21 | 21 | 8 (1) | 1 | 2 | 16 | 18 | 6,616,585 | 1 |

| 2000 | 20 | 20 | 9 (3) | 4 | 1 | 17 | 20 | 9,188,321 | 1 |

| 2001 | 19 | 19 | 5 (1) | 0 | 1 | 9 | 18 | 5,687,777 | 1 |

| 2002 | 18 | 18 | 5 (2) | 2 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 6,912,625 | 1 |

| 2003 | 18 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 6,673,413 | 2 |

| 2004 | 19 | 19 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 18 | 5,365,472 | 4 |

| 2005 | 21 | 19 | 6 (2) | 4 | 2 | 13 | 17 | 10,628,024 | 1 |

| 2006 | 15 | 14 | 8 (2) | 1 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 9,941,563 | 1 |

| 2007 | 16 | 16 | 7 (1) | 3 | 0 | 12 | 15 | 10,867,052 | 1 |

| 2008 | 6 | 6 | 4 (1) | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 5,775,000 | 2 |

| 2009 | 17 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 10,508,163 | 1 |

| 2010 | 12 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 1,294,765 | 68 |

| 2011 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 660,238 | 128 |

| 2012 | 19 | 17 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 13 | 6,133,158 | 2 |

| 2013 | 16 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 8,553,439 | 1 |

| 2013–14 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 108,275 | 201 |

| 2014–15 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 448,598 | 162 |

| 2015–16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| 2016–17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| 2017–18 | 18 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 12 | 5,443,841 | 7 |

| 2018–19 | 12 | 9 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 3,199,615 | 24 |

| 2019–20 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2,083,038 | 38 |

| 2020–21 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64,200 | 223 |

| 2021–22 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43,500 | 225 |

| 2022–23 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59,560 | 226 |

| 2024* | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44,400 | 190 |

| Career* | 375 | 339 | 82 (15) | 31 | 19 | 199 | 270 | 120,999,166 | 1[185] |

*As of April 15, 2024

Playing style

When Woods first joined the PGA Tour in 1996, his long drives had a large impact on the world of golf,[186] but he did not upgrade his equipment in the following years. He insisted upon the use of True Temper Dynamic Gold steel-shafted clubs and smaller steel clubheads that promoted accuracy over distance.[187] Many opponents caught up to him, and Phil Mickelson even made a joke in 2003 about Woods using "inferior equipment", which did not sit well with Nike, Titleist, or Woods.[188] During 2004, Woods finally upgraded his driver technology to a larger clubhead and graphite shaft, which, coupled with his clubhead speed, again made him one of the tour's longest players off the tee.

Despite his power advantage, Woods has always focused on developing an excellent all-around game. Although in recent years[when?] he has typically been near the bottom of the Tour rankings in driving accuracy, his iron play is generally accurate, his recovery and bunker play is very strong, and his putting (especially under pressure) is possibly his greatest asset. He is largely responsible for a shift to higher standards of athleticism amongst professional golfers, and is known for utilizing more hours of practice than most.[189][190][191]

From mid-1993 (while he was still an amateur) until 2004, Woods worked almost exclusively with leading swing coach Butch Harmon. From mid-1997, Harmon and Woods fashioned a major redevelopment of Woods's full swing, achieving greater consistency, better distance control, and better kinesiology. The changes began to pay off in 1999.[192] Woods and Harmon eventually parted ways. From March 2004 to 2010, Woods was coached by Hank Haney, who worked on flattening his swing plane. Woods continued to win tournaments with Haney, but his driving accuracy dropped significantly. Haney resigned under questionable circumstances in May 2010[193] and was replaced by Sean Foley.[194]

Fluff Cowan served as Woods's caddie from the start of his professional career until Woods dismissed him in March 1999.[195] He was replaced by Steve Williams, who became a close friend of Woods and is often credited with helping him with key shots and putts.[196] In June 2011, Woods dismissed Williams after he caddied for Adam Scott in the U.S. Open[197] and replaced him with friend Bryon Bell on an interim basis. Joe LaCava, a former caddie of both Fred Couples and Dustin Johnson, was hired by Woods shortly after[198] and has remained Woods's caddie since then.

Other ventures

TGR Foundation

The TGR Foundation was established in 1996 by Woods and his father Earl as the Tiger Woods Foundation with the primary goal of promoting golf among inner-city children.[199] The foundation has conducted junior golf clinics across the country, and sponsors the Tiger Woods Foundation National Junior Golf Team in the Junior World Golf Championships.[200][201] As of December 2010, TWF employed approximately 55 people.[202][203]

The foundation operates the Tiger Woods Learning Center, a $50-million, 35,000-square-foot (3,300 m2) facility in Anaheim, California, providing college-access programs for underserved youth.[200][202][204] The TWLC opened in 2006 and features seven classrooms, extensive multi-media facilities and an outdoor golf teaching area.[200] The center has since expanded to four additional campuses: two in Washington, D.C.; one in Philadelphia; and one in Stuart, Florida.[204]

The foundation benefits from the annual Chevron World Challenge and AT&T National golf tournaments hosted by Woods.[202] In October 2011, the foundation hosted the first Tiger Woods Invitational at Pebble Beach.[205] Other annual fundraisers have included the concert events Block Party, last held in 2009 in Anaheim, and Tiger Jam, last held in 2011 in Las Vegas after a one-year hiatus.[202][206]

Tiger Woods Design

In November 2006, Woods announced his intention to begin designing golf courses around the world through a new company, Tiger Woods Design.[207] A month later, he announced that the company's first course would be in Dubai as part of a 25.3-million-square-foot development, The Tiger Woods Dubai.[208] The Al Ruwaya Golf Course was initially expected to finish construction in 2009.[208] As of February 2010, only seven holes had been completed; in April 2011, The New York Times reported that the project had been shelved permanently.[209][210] In 2013, the partnership between Tiger Woods Design and Dubai Holding was dissolved.[211]

Tiger Woods Design has taken on two other courses, neither of which has materialized. In August 2007, Woods announced The Cliffs at High Carolina, a private course in the Blue Ridge Mountains near Asheville, North Carolina.[212] After a groundbreaking in November 2008, the project suffered cash flow problems and suspended construction.[210] In 2019 the 800-acre site was sold for $19.3 million and in 2024 550 acres of that were listed for about the same price. While no evidence of Woods' involvement has been found, the listing shows that development plans are still on file.[213] A third course, in Punta Brava, Mexico, was announced in October 2008, but incurred delays due to issues with permits and an environmental impact study.[210][214] Construction on the Punta Brava course has not yet begun.[210]

These projects have encountered problems that have been attributed to factors that include overly optimistic estimates of their value, declines throughout the global economy (particularly the U.S. crash in home prices), and the decreased appeal and marketability of Woods following his 2009 infidelity scandal.[210]

Writings

Woods wrote a golf instruction column for Golf Digest magazine from 1997 to February 2011.[215] In 2001, he wrote a best-selling golf instruction book, How I Play Golf, which had the largest print run of any golf book for its first edition, 1.5 million copies.[216] In March 2017, he published a memoir, The 1997 Masters: My Story, co-authored by Lorne Rubenstein, which focuses on his first Masters win.[217] In October 2019, Woods announced he would be writing a memoir book titled Back.[218]

NFT

Tiger Woods' "Iconic Fist Pumps Collection" is his first digital Non-fungible token (NFT) collection that launched on the DraftKings Marketplace in collaboration with Autograph.io on September 28, 2021. Autograph is an NFT platform that was co-founded by Tom Brady that helped launch NFT projects with some of the biggest names in sports, including Usain Bolt, Rafael Nadal, Wayne Gretzky, and Tony Hawk. Woods' first collection offered 10,000 digital pictures of Tiger Woods' iconic moments ranging from $12 to $1,500, and 300 of those NFTs were also accompanied by his official digital signature.[219] The NFTs launched on the Autograph platform grants fans unique access to exclusive content, first dibs on digital collectibles, custom-made merchandise, and access to private in-person events depending on the varying utility of each NFT.[220]

Sun Day Red

Woods partnered with TaylorMade to launch his golf apparel line, dubbed "Sun Day Red". The line was announced on February 12, 2024, and featured Woods' signature red shirt.[221][222]

Personal life

Relationships and children

In November 2003, Woods became engaged to Elin Nordegren, a Swedish former model and daughter of former minister of migration Barbro Holmberg and radio journalist Thomas Nordegren.[223] They were introduced during The Open Championship in 2001 by Swedish golfer Jesper Parnevik, who had employed her as an au pair. They married on October 5, 2004, at the Sandy Lane resort in Barbados, and lived at Isleworth, a community in Windermere, a suburb of Orlando, Florida.[224][225] In 2006, they purchased a $39-million estate in Jupiter Island, Florida, and began constructing a 10,000-square-foot home; Woods moved there in 2010 following the couple's divorce.[168][225]

Woods and Nordegren's first child was a daughter born in 2007, whom they named Sam Alexis Woods. Woods chose the name because his own father had always called him Sam.[226] Their son, Charlie Axel Woods, was born in 2009.[227]

Infidelity scandal and fallout

In November 2009, the National Enquirer published a story claiming that Woods had an extramarital affair with New York City nightclub manager Rachel Uchitel, who denied the claim.[228] Two days later, around 2:30 a.m. on November 27, Woods was driving from his Florida mansion in his Cadillac Escalade SUV when he collided with a fire hydrant, a tree, and several hedges near his home.[229] He was treated for minor facial lacerations and received a ticket for careless driving.[229][230] Following intense media speculation about the cause of the crash, Woods released a statement on his website and took sole responsibility for the crash, calling it a "private matter" and crediting his wife for helping him from the car.[231] On November 30, Woods announced that he would not be appearing at his own charity golf tournament (the Chevron World Challenge) or any other tournaments in 2009 because of his injuries.[232]

On December 2, following Us Weekly magazine's previous day reporting of a purported mistress and subsequent release of a voicemail message allegedly left by Woods for the woman,[233] Woods released a further statement. He admitted transgressions and apologized to "all of those who have supported [him] over the years", while reiterating his and his family's right to privacy.[228][234] Over the next few days, more than a dozen women claimed in various media outlets to have had affairs with Woods.[6] On December 11, he released a third statement admitting to infidelity and he apologized again. He also announced that he would be taking "an indefinite break from professional golf."[6]

In the days and months following Woods's admission of multiple infidelities, several companies re-evaluated their relationships with him. Accenture, AT&T, Gatorade, and General Motors completely ended their sponsorship deals, while Gillette suspended advertising featuring Woods.[89][235] TAG Heuer dropped Woods from advertising in December 2009 and officially ended their deal when his contract expired in August 2011.[89] Golf Digest magazine suspended Woods's monthly column beginning with the February 2010 issue.[236] In contrast, Nike continued to support Woods, as did Electronic Arts, which was working with Woods on the game Tiger Woods PGA Tour Online.[237] A December 2009 study estimated the shareholder loss caused by Woods's affairs to be between $5 billion and $12 billion.[238]

On February 19, 2010, Woods gave a televised statement in which he said he went through a 45-day therapy program that began at the end of December. He again apologized for his actions. "I thought I could get away with whatever I wanted to", he said. "I felt that I had worked hard my entire life and deserved to enjoy all the temptations around me. I felt I was entitled. Thanks to money and fame, I didn't have to go far to find them. I was wrong. I was foolish." He said he did not know yet when he would be returning to golf.[88][239] On March 16, he announced that he would play in the 2010 Masters.[240]

After six years of marriage, Woods and Nordegren divorced on August 23, 2010.[241]

Subsequent relationships

On March 18, 2013, Woods announced that he and Olympic gold medal skier Lindsey Vonn were dating.[242] They split up in May 2015.[243] From November 2016 to August 2017, Woods was rumored to be in a relationship with stylist Kristin Smith.[244] Between late 2017 and late 2022, Woods was in a relationship with restaurant manager Erica Herman. However, in early 2023, Herman filed suit against Woods in relation to a non-disclosure agreement, alleging that it violates the Speak Out Act. Herman claimed that she was owed $30 million after an oral agreement was breached when Woods' trust's employees "locked her out of the Residence, removed her personal belongings, and informed her she could not return."[245]

2017 DUI arrest

On May 29, 2017, Woods was arrested near his home in Jupiter Island, Florida, by the Jupiter Police Department at about 3:00 am. EDT for driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs. He was asleep in his car, which was stationary in a traffic lane with its engine running. He later stated that he took prescription drugs and did not realize how they might interact together.[246][247][248]On July 3, 2017, Woods tweeted that he completed an out-of-state intensive program to tackle an unspecified issue.[249] At his arraignment on August 9, 2017, Woods had his attorney Douglas Duncan submit a not guilty plea for him and agreed to take part in a first-time driving under the influence offender program and attend another arraignment on October 25.[250][251]

At a hearing on October 27, 2017, Woods pleaded guilty to reckless driving. He received a year of probation, was fined $250, and ordered to undergo 50 hours of community service along with regular drug tests. He was not allowed to drink alcohol during the probation, and if he violated the probation he would be sentenced to 90 days in jail with an additional $500 fine.[252]

2021 car crash

On February 23, 2021, Woods survived a serious rollover car crash in Rancho Palos Verdes, California.[253] The wreck was a single-vehicle collision and Woods was the sole occupant of the vehicle, which was traveling north along Hawthorne Boulevard.[254][255][256]

He was taken to the Harbor–UCLA Medical Center by ambulance.[257][253] The incident was under investigation by the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, which said the car "sustained major damage," and that Woods was driving over 80 mph, nearly twice the speed limit, before he crashed. No charges were filed.[258][253][259][260] Woods's agent later said that he sustained multiple leg injuries and had surgery for non-life-threatening injuries.[253][255][259]

Other pursuits

Woods was raised as a Buddhist. He actively practiced his faith from childhood until well into his adult professional golf career.[261] In a 2000 article, Woods was quoted as saying that he "believes in Buddhism ... not every aspect, but most of it."[262] He has attributed his deviations and infidelity to his losing track of Buddhism. He said, "Buddhism teaches me to stop following every impulse and to learn restraint. Obviously I lost track of what I was taught."[263]

Woods is registered as an independent voter.[264] In January 2009, Woods delivered a speech commemorating the military at the We Are One: The Obama Inaugural Celebration at the Lincoln Memorial.[265] In April 2009, Woods visited the White House while promoting the golf tournament he hosts, the AT&T National.[266] In December 2016 and again in November 2017, Woods played golf with President Donald Trump at the Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach.[267]

Bibliography

- 2001: How I Play Golf, Warner Books, ISBN 978-0-446-52931-0

- 2017: The 1997 Masters: My Story (with Lorne Rubenstein), Grand Central Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4555-4358-8

See also

- Career Grand Slam Champions

- List of golfers with most European Tour wins

- List of golfers with most PGA Tour wins

- List of golfers with most wins in one PGA Tour event

- List of longest PGA Tour win streaks

- List of men's major championships winning golfers

- List of world number one male golfers

- Most PGA Tour wins in a year

Notes

References

- ^ a b "Tiger Woods – Profile". PGA Tour. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ "Week 24 1997 Ending 15 Jun 1997" (pdf). OWGR. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ 2009 European Tour Official Guide Section 4, p. 577 PDF 21. European Tour. Retrieved April 21, 2009. Archived January 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b

- Chase, Chris (April 13, 2018). "Who is the greatest golfer ever: Tiger or Jack?". USA Today. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Diaz, Jaime (January 23, 2018). "What made Tiger Woods great – and can again". Golf Digest. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "Phil: Tiger in prime played best golf ever". ESPN. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Harig, Bob (March 11, 2020). "Tiger Woods to be inducted into World Golf Hall of Fame in 2021". ESPN.

- ^ a b c d Dahlberg, Tim (December 12, 2009). "Two weeks that shattered the legend of Tiger Woods". Fox News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "Westwood becomes world number one". BBC News. October 31, 2010.

- ^ a b c Schlabach, Mark (November 13, 2011). "Tiger Woods moves to 50th in rankings". ESPN. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ "Complete list of Tiger Woods' injuries". PGA Tour. Associated Press. March 5, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ DiMeglio, Steve (August 1, 2018). "With game on point, Tiger Woods is in perfect place to win again at Firestone". USA Today. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Reid, Philip (August 14, 2018). "For the new Tiger Woods, second place is far from first loser". The Irish Times. Dublin. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Kelley, Brent (October 20, 2009). "Woods Clinches PGA Player of the Year Award". About.com: Golf. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "Tracking Tiger". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Powers, Christopher. "18 still remarkable stats from Jack Nicklaus' illustrious career". Golf Digest. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Rogers, Katie (May 6, 2019). "'I've Battled,' Tiger Woods Says as He Accepts Presidential Medal of Freedom". The New York Times. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Macaya, Melissa (February 23, 2021). "Tiger Woods injured in car crash". CNN. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Rapaport, Dan (November 29, 2021). "Exclusive: Tiger Woods discusses golf future in first in-depth interview since car accident". Golf Digest. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ "Tiger Woods Biography – childhood, children, parents, name, history, mother, young, son, old, information, born". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ "Tiger Woods' father, Earl, succumbs to cancer". ESPN. Associated Press. May 5, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Kelley, Brent (May 6, 2019). "Tiger Woods' Parents: Meet Mom and Dad". Thoughtco.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ His Father's Son: Earl and Tiger Woods, by Tom Callahan, 2010; The Wicked Game, by Howard Sounes, 2004

- ^ Younge, Gary (May 28, 2010). "Tiger Woods: Black, white, other | racial politics". The Guardian. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

Woods is indeed a rich mix of racial and ethnic heritage. His father, Earl, was of African-American, Chinese and Native American descent. His mother, Kultida, is of Thai, Chinese and Dutch descent

- ^ "Earl Woods" (obituary). The Daily Telegraph (June 5, 2006). Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ "Earning His Stripes". AsianWeek. October 11, 1996. Archived from the original on January 16, 1998. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ Garber, Greg (May 22, 2002). "Will Tiger ever show the color of his stripes?". ESPN. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Woods stars on Oprah, says he's 'Cablinasian'". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Associated Press. April 23, 1997. Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ Callahan, Tom (May 9, 2006). "Tiger's dad gave us all some lessons to remember". Golf Digest. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Chandler, Rick (June 7, 2012). "Tiger Woods' niece makes her major pro golf tourney debut today". Off the Bench. NBC Sports. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ Training a Tiger: Raising a Winner in Golf and in Life, by Earl Woods and Pete McDaniel, 1997.

- ^ Rogers, Carroll (March 11, 1999). "Smoltz, Woods change their games for day". The Atlanta Constitution. p. E2. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Play Golf Where Tiger Became Tiger". Golf Magazine.

- ^ "Tiger Woods Timeline". Infoplease. Retrieved May 12, 2007.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Training A Tiger, by Earl Woods and Pete McDaniel, 1997, p. 64.

- ^ "1984 Champions". Junior World Golf Championships. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ The Wicked Game: Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, and the Story of Modern Golf, by Howard Sounes, 2004, William Morrow, New York, ISBN 0-06-051386-1, p. 187; originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Nike's Tiger Woods professional career launch advertisement, August 1996.

- ^ "1985 Champions". Junior World Golf Championships. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "1988 Champions". Junior World Golf Championships. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "1989 Champions". Junior World Golf Championships. Archived from the original on September 21, 2007. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "1990 Champions". Junior World Golf Championships. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "1991 Champions". Junior World Golf Championships. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^

- Training A Tiger: A Father's Guide to Raising a Winner in Both Golf and Life, by Earl Woods with Pete McDaniel, 1997, HarperCollins, New York, ISBN 0-06-270178-9, p. 23;

- The Wicked Game: Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, and the Story of Modern Golf, by Howard Sounes.

- ^ a b His Father's Son: Earl and Tiger Woods, by Tom Callahan, 2010

- ^ Training A Tiger: A Father's Guide to Raising a Winner in Both Golf and Life, by Earl Woods with Pete McDaniel, 1997, HarperCollins, New York, ISBN 0-06-270178-9, p. 180.

- ^ Jack Nicklaus: Memories and Mementos from Golf's Golden Bear, by Jack Nicklaus with David Shedloski, 2007, Stewart, Tabori & Chang, New York, ISBN 1-58479-564-6, p. 130.

- ^ "1991 U.S. Junior Amateur". U.S. Junior Amateur. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "1992 U.S. Junior Amateur". U.S. Junior Amateur. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Tiger Woods". IMG Speakers. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ "1993 U.S. Junior Amateur". U.S. Junior Amateur. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Sounes, p. 277.

- ^ Ramasubramanian, Deepa (August 20, 2023). "This unique Tiger Woods record is sure to make your jaw drop". www.sportskeeda.com. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ "Notable Past Players". International Golf Federation. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ Thomsen, Ian (September 9, 1995). "Ailing Woods Unsure for Walker Cup". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ The Wicked Game: Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, and the Story of Modern Golf, by Howard Sounes, 2004, William Morrow, New York, ISBN 0-06-051386-1, information listed on inset photos between pages 168 and 169.

- ^

- "Famous People – Speech Differences and Stutter". Disabled World. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- "Tiger Woods writes letter of support to fellow stutterer". The Guardian. May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- Sirak, Ron (May 12, 2015). "Former stutterer Tiger Woods writes letter to young boy being bullied". Golf Digest. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Tiger Woods Writes Letter to Boy With Stuttering Problem". ABC News. May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Stanford Men's Golf Team Tiger Woods". Stanford Men's Golf Team. April 8, 2003. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- ^ Rosaforte, Tim (1997). Tiger Woods: The Makings of a Champion. St. Martin's Press. pp. 84, 101. ISBN 0-312-96437-4.

- ^ "PAC-10 Men's Golf" (PDF). PAC-10 Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "Tiger Woods through the Ages..." Geocities. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ Sounes, p. 277

- ^ "Tiger Woods Captures 1996 NCAA Individual Title". Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 29, 2006. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ Rosaforte 1997, p. 160.

- ^ Wood, Robert W. (January 23, 2013). "Tiger Woods Moved Too, Says Mickelson Was Right About Taxes". Forbes. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ Sirak, Ron. "10 Years of Tiger Woods Part 1". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ Sirak, Ron. "Golf's first Billion-Dollar Man". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Reilly, Rick (December 23, 1996). "1996: Tiger Woods". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ Sirak, Ron. "10 Years of Tiger Woods Part 2". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ "Woods scoops world rankings award". BBC Sport. London. March 15, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Diaz, Jaime. "The Truth about Tiger". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on April 15, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Woods is PGA Tour player of year". The Topeka Capital-Journal. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Tiger Woods undergoes second laser eye surgery". Golf Today. May 15, 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ "Woods has second laser eye surgery". Golf Magazine. May 15, 2007. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ Garrity, John (June 26, 2000). "Open and Shut". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ Sirak, Ron. "10 Years of Tiger Woods Part 3". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ *Price, S.L. (April 3, 2000). "Tunnel Vision". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- Yocom, Guy (July 2000). "50 Greatest Golfers of All Time: And What They Taught Us". Golf Digest. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ "The remarkable drive of Tiger Woods". CNN. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Shedloski, Dave (July 27, 2006). "Woods is starting to own his swing". PGA Tour. Archived from the original on September 22, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Hard labor pays off for Singh". Sports Illustrated. Reuters. September 7, 2004. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Verdi, Bob. "A Rivalry is Reborn". Golf World. Archived from the original on May 14, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^

- Morfit, Cameron (March 6, 2006). "Tiger Woods's Rivals Will Be Back. Eventually". Golf Magazine. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- Hack, Damon (April 10, 2006). "Golf: Notebook; Trouble on Greens Keeps Woods From His Fifth Green Jacket". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ Litsky, Frank (May 4, 2006). "Earl Woods, 74, Father of Tiger Woods, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ "Man of the Year". PGA. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ "Tiger Woods undergoes knee surgery". Agence France-Presse. April 15, 2008. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ^ *"Tiger puts away Mediate on 91st hole to win U.S. Open". ESPN. Associated Press. June 16, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- Savage, Brendan (June 25, 2008). "Rocco Mediate still riding U.S. Open high into Buick Open". The Flint Journal. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Lage, Larry (June 26, 2008). "Mediate makes the most of his brush with Tiger". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- ^

- Steinberg, Mark (June 18, 2008). "Tiger Woods to Undergo Reconstructive Knee Surgery and Miss Remainder of 2008 Season". TigerWoods.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- Dorman, Larry (June 19, 2008). "Woods to Have Knee Surgery, Ending His Season". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Donegan, Lawrence (June 17, 2008). "Woods savours 'greatest triumph' after epic duel with brave Mediate". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- ^ "Tiger's Return Expected To Make PGA Ratings Roar". The Nielsen Company 2009. February 25, 2009. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^

- Dahlberg, Tim (March 1, 2009). "Anything can happen: It did in Tiger's return". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- Ferguson, Doug (October 12, 2009). "Americans win the Presidents Cup". Cumberland Times-News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- Barber, Phil (October 11, 2009). "Americans win the Presidents Cup". The Press Democrat. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ a b "Tiger Woods apologises to wife Elin for affairs". BBC Sport. London. February 19, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c "AT&T cuts connection with Woods". ESPN. Associated Press. January 1, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "Mickelson wins Masters; Tiger 5 back". ESPN. April 11, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ Harig, Bob (May 1, 2010). "Woods misses sixth PGA Tour cut". ESPN. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^

- pgatour.com, Official World Golf Ranking for March 27, 2011

- pgatour.com, Official World Golf Ranking for April 11, 2011

- pgatour.com, 2011 Masters tournament data

- ^

- http://www.tigerwoods.com, June 7, 2011[failed verification]

- Howard Sounes: The Wicked Game[full citation needed]

- ^ "Tiger Woods' impressive history at Bay Hill". PGA Tour. March 3, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ Crouse, Karen (December 4, 2011). "After Two-Year Drought, Woods Wins With Flourish". The New York Times.

- ^ Evans, Farrell (February 24, 2012). "Nick Watney eliminates Tiger Woods". ESPN. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ "Tiger wins Memorial to match Nicklaus on 73 wins". The Times of India. June 4, 2012. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ "Tiger Woods wins AT&T to pass Jack Nicklaus record". BBC Sport. July 2, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ Evans, Farrell (January 29, 2013). "Tiger takes Torrey for 75th tour win". ESPN. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Tiger Woods prevails at Doral". ESPN. Associated Press. March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Tiger returns to No. 1, wins Bay Hill". ESPN. Associated Press. March 25, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Boren, Cindy (March 27, 2013). "Tiger Woods Nike ad causes a stir with 'winning takes care of everything' message". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Is Tiger Woods facing disqualification at Masters?". CBS Sports. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Tiger Woods walks off at Honda Classic". bunkered. March 3, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.