2014–2017 Brazilian drought

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (November 2017) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The 2014–17 Brazilian drought is a severe drought affecting the southeast of Brazil including the metropolitan areas of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In São Paulo, it has been described as the worst drought in 100 years.[1][2] The metropolis of São Paulo appeared to be affected the most and by the beginning of February many of its residents were subjected to sporadic water cutoffs.[3] Rain at the end of 2015 and in early 2016 brought relief, however, long term problems in water supply remain in São Paulo state.[4]

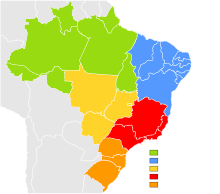

Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo were still being affected by drought in 2016 due to the 2014–16 El Niño event. In these areas the rains are irregular since 2014 and the drought worsened from 2015.[5][6][7] Over 50% of Brazil was affected, as the drought spanned sections of all nine northeastern states. Between 2012-2015, the federal government decreed a state of “public calamity” over 6,200 times due to the droughts.[8]

This is the worst drought in Brazil in the last 100 years, according to the O Estado de S. Paulo in September 2017.[9]

Extent

[edit]

Usually the rainy season starts in November,[10] but lack of rain in the 2014/15 season led to a major shortfall in the water supply in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais.[1][11] With major reservoirs operating at their lowest capacity (the main reservoir system of Cantareira supplying São Paulo being at only 6% of its capacity in early February[1][12]) officials at São Paulo warned about extended rationing as water may run out before the next rainy season in November 2015.[10] In response, the water utility of São Paulo, Sabesp, has reduced water pressure in the system. It also started to impose punitive tariffs on users who use more than in previous years.[13] By early February residents had started to recycle and hoard water.[12]

At the beginning of the dry season in early May 2015, the water crisis continued and water reservoirs in the São Paulo area were insufficiently filled.[14] Work was underway to link up various reservoirs to make better use of existing water resources.[15] By October 2015 the Cantareira reservoirs contained 12% of their capacity while the polluted Billings Reservoir had 20%.[16]

With the arrival of the rainy season at the end of 2015, the drought situation improved. In February 2016 torrential downpours caused flooding in São Paulo.[17] Water levels at Cantareira had recovered from 20 percent capacity at the beginning of December to almost 50 percent by mid February 2016.[4] However, Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo still being affected by drought in 2016, and in 5 May the Espírito Santo Government declared a state of emergency across the state as the drought worsened.[7]

There was concern that an unresolved water crisis may impact the 2016 Olympic Games.[18] In 2017, the rains remained extremely irregular in Minas Gerais,[19] Espírito Santo[20] and most parts of the regions Central-West and Northeast. This is the worst drought in Brazil in the last 100 years, according to the O Estado de S. Paulo in September 2017.[9]

Potential causes

[edit]The drought situation is not unexpected. São Paulo is experiencing its third consecutive year of diminished rain falls.[10] A drought situation was already experienced in early 2014.[21] Water management is poor, pipes leak, and the infrastructure is old.[1] Past reports by scientists, environmentalists and technical experts were overridden by real estate developers and industrial and agricultural interests.[10] Further, lack of protection of watersheds and reservoirs has polluted water sources and made it difficult to bring usable water to the market.[10] The expansion of deforestation activities into the Amazon basin has been linked to the reduction of rainfall in the south of Brazil.[1][3][10] Even if the Amazon's evaporation was enough to generate flying rivers, urban heat islands coupled with a heat wave prevented the arrival of humid air masses that generate rain. In turn, Brazilian regions on the way to the Southeast had an uprise of rain, to the point the Central-West and Southern regions suffered from floods.[22]

History

[edit]

Rainfall was well below the climatological average in most of Southeast and Southern Brazil after October 2013, and cities such as Porto Alegre, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro experienced record heat in February 2014.[23][24][25] Due to the absence of cloudiness, the incidence of solar radiation was about 40% above normal over the Southeast in 2014, while the average temperature was 5 °C above normal. The lack of clouds and intense sunshine also left the sea temperature on the Southeast coast around 3 °C above average in the 2013–2014 summer,[26] which was considered the hottest and driest in Brazil in 71 years. With the absence of precipitation, associated with high temperatures and low relative humidity, damage to agriculture and water supply began to be recorded,[27][28] in addition to a reduction in the level of reservoirs of hydroelectric plants.[29]

Effect on crop production

[edit]Brazil is the world's third-largest agricultural exporter, and the sector represents approximately 6% of the country's GDP. Irrigation for agriculture accounts for 72% of water use in Brazil, compared to just 9% for urban consumption. Less water supply for crop production lead to "The Agricultural Economy Institute" stating that 2014 accounted for São Paulo's worst agricultural losses in half a century.[30]

The irregular rainfall pattern contributed to a reduction in crop production through the drought period, due to an atmospheric blockage which prevented a cold front from advancing over key crop regions in Brazil, the world's largest exporter of coffee, sugar, soy and beef. In 2014 the drought wiped out a third of the country's coffee crop in some areas, which caused global coffee arabica prices to rise 50% over the year.[31] In 2015 coffee trees had not recovered from the extreme heat and drought quick enough, triggering another arabica price rally. Crop production of soy, one of the country's largest export crops, decreased by 17% during the drought.[32]

The Cemaden's Rain Monitoring System showed that severe droughts were observed in the states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, they are both the largest regions for soybean production and fourth-largest beef producers in Brazil.[8]

Effect on hydropower generation

[edit]As 70% of Brazil's electricity is generated by hydropower, the lack of water lead to energy rationing in addition to water rationing.[33][13] In response to decreased hydroelectric power, rolling power cuts were instituted.[18] Water and electricity prices were expected to rise a month or two after the elections in October. Power utilities In Brazil stated that the loss of hydro-generating capacity had cost them 15.8bn reais (£4.3bn). Most of this was spent on more expensive alternative such as oil and other carbon-based fuels that filled the gap in electricity supply. This in turn pushed up Brazil's greenhouse gas emissions in the years of 2015 to 2017.[34]

Potential solutions

[edit]Analysts see the crisis as a relatively short-term stressor but believe that it has the potential to be the "catalyst" to solve specifically São Paulo's water problems.[13] Short term solutions include drilling more wells and more recycling of water. Long term solutions include the transfer of more water from additional river basins. Thus, a new 15 km connection has been authorised to be built to bring water from the Paraiba do Sul river basin to the Cantareira system, watersheds that have distinct aquatic biota.[35][13] These water diversion projects transport water between isolated river basins, without regard for ecology or aquatic biodiversity. Also, repair of leaking pipes is estimated to save 6% of total municipal water consumption in São Paulo.[13]

In 2018, steep fines were implement for above-average water use, but some fear the measure came too late. The Cantareira reservoir was at 6.8% capacity at the start of 2018, even after several afternoons of violent summer rainstorms in São Paulo.[36]

See also

[edit]- 2023–2024 South American drought

- Water management in the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo

- Grande Seca

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Lourdes Garcia-Navarro, Paula Moura (February 10, 2015). "A Historic Drought Grips Brazil's Economic Capital". NPR. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Brazil hit by worst drought in decades". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ a b Simon Romero (February 16, 2015). "Taps Start to Run Dry in Brazil's Largest City". The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b C. Stauffer (February 18, 2016). "Drought ends in Brazil's Sao Paulo but future still uncertain". Reuters. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ Josélia Pegorim (November 2, 2015). "El Niño acentua a seca no rio Doce" (in Portuguese). Climatempo. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ Terra (October 7, 2015). "Seca continua no ES e em MG" (in Portuguese). Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Patrícia Scalzer (May 5, 2016). "Seca faz Espírito Santo decretar situação de emergência" (in Portuguese). Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Brazil's agribusiness to suffer from worst drought season". The Brazilian Report. 2018-07-24. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ a b André Borges (September 23, 2017). "Maiores represas do País enfrentam seca histórica" (in Portuguese). O Estado de S. Paulo. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Marussia Whately, Rebeca Lerer (February 11, 2015). "Brazil drought: water rationing alone won't save São Paulo". The Guardian. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Brazil's most populous region facing worst drought in 80 years". BBC. January 24, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ a b "Brazil drought prompts drastic measures to save water". Al Jazeera. February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Sao Paulo Drought Could Benefit Brazil". Stratfor. February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ Romero, Simon (2015-02-16). "Taps Start to Run Dry in Brazil's Largest City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ Romero, Simon (2015-02-16). "Taps Start to Run Dry in Brazil's Largest City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ Jon Gerberg (October 13, 2015). "A Megacity Without Water: São Paulo's Drought". Time magazine. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- ^ Everton Fox (February 26, 2015). "Drought-stricken Sao Paulo hit by floods". Al Jazeera. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Matthew Wheeland (May 4, 2015). "Brazil struggles with drought and pollution as Olympics loom large". The Guardian. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Gustavo Werneck (August 20, 2017). "Estiagem e degradação deixam rios e lagoas de Minas em situação dramática" (in Portuguese). Estado de Minas. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ Gazeta Online (October 2, 2017). ""Fantasma" do racionamento assombra o Espírito Santo" (in Portuguese). Gazeta Online. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ Phillips, Dom (21 May 2014). "São Paulo faces a critical water shortage as the World Cup prepares to kick off". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Camila Almeida (November 2014). "O Brasil secou". Superinteressante (in Portuguese). Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ O Vale (11 February 2014). "Calor de 40°C bate recorde dos últimos 53 anos em Taubaté". Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Fantástico (9 February 2014). "Especialistas explicam calor extremo deste verão no Brasil". G1. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Josélia Pegorim (9 February 2015). "Chuva no Sudeste diminui nos próximos dias". Climatempo. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Léo Ramos Chaves (8 July 2019). "Uma possível origem das estiagens de verão do Sudeste". Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP). Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ R7.com (7 March 2014). "Estiagem histórica: nível do Cantareira chega a 15,8%". Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Veja (7 February 2014). "Chuvas devem aliviar seca no Sudeste e no Centro-Oeste". Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Folha Uol (18 February 2014). "Seca faz reaparecer em Itaipu ruínas de cemitério submerso". Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Glickhouse, Rachel. "Brazil Update: Historic Drought Takes Toll on Agriculture". AS/COA. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ Generale, O. M. A. "The effects of drought in Brazil". www.wfo-oma.org. Retrieved 2019-03-15.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Brazil Water Supply, Crops Still at Risk a Year after Epic Drought". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ Joe Leahy (February 11, 2015). "São Paulo drought raises fears of Brazil energy crisis". Financial Times. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (2014-09-05). "Brazil drought crisis leads to rationing and tensions". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ Agostinho, Ângelo Antônio; Pelicice, Fernando Mayer; Orsi, Mario Luís; Magalhães, André Lincoln Barroso de; Lima-Junior, Dilermando Pereira; Daga, Vanessa Salete; Azevedo-Santos, Valter M.; Vitule, Jean Ricardo Simões (2015-03-27). "Brazil's drought: Protect biodiversity". Science. 347 (6229): 1427–1428. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1427S. doi:10.1126/science.347.6229.1427-b. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25814574.

- ^ "Brazil Water Supply, Crops Still at Risk a Year after Epic Drought". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- Water in Brazil

- Climate of Brazil

- Droughts in South America

- Weather events in Brazil

- Environment of Espírito Santo

- Environment of Minas Gerais

- Environment of Rio de Janeiro (state)

- Environment of São Paulo (state)

- 2014 disasters in Brazil

- 2015 disasters in Brazil

- 2016 disasters in Brazil

- 2017 disasters in Brazil

- 2014 natural disasters

- 2015 natural disasters

- 2016 natural disasters

- 2017 natural disasters

- 2014 in the environment

- 2015 in the environment

- 2016 in the environment

- 2017 in the environment

- 2014 droughts

- 2015 droughts

- 2016 droughts

- 2017 droughts

- Droughts in Brazil