2010s global surveillance disclosures

| Part of a series on |

| Global surveillance |

|---|

| Disclosures |

| Systems |

| Selected agencies |

| Places |

| Laws |

| Proposed changes |

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

National Security Agency surveillance |

|---|

|

| GCHQ surveillance |

|---|

During the 2010s, international media reports revealed new operational details about the Anglophone cryptographic agencies' global surveillance[1] of both foreign and domestic nationals. The reports mostly relate to top secret documents leaked by ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden. The documents consist of intelligence files relating to the U.S. and other Five Eyes countries.[2] In June 2013, the first of Snowden's documents were published, with further selected documents released to various news outlets through the year.

These media reports disclosed several secret treaties signed by members of the UKUSA community in their efforts to implement global surveillance. For example, Der Spiegel revealed how the German Federal Intelligence Service (German: Bundesnachrichtendienst; BND) transfers "massive amounts of intercepted data to the NSA",[3] while Swedish Television revealed the National Defence Radio Establishment (FRA) provided the NSA with data from its cable collection, under a secret agreement signed in 1954 for bilateral cooperation on surveillance.[4] Other security and intelligence agencies involved in the practice of global surveillance include those in Australia (ASD), Britain (GCHQ), Canada (CSE), Denmark (PET), France (DGSE), Germany (BND), Italy (AISE), the Netherlands (AIVD), Norway (NIS), Spain (CNI), Switzerland (NDB), Singapore (SID) as well as Israel (ISNU), which receives raw, unfiltered data of U.S. citizens from the NSA.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

On June 14, 2013, United States prosecutors charged Edward Snowden with espionage and theft of government property. In late July 2013, he was granted a one-year temporary asylum by the Russian government,[13] contributing to a deterioration of Russia–United States relations.[14][15] Toward the end of October 2013, the British Prime Minister David Cameron warned The Guardian not to publish any more leaks, or it will receive a DA-Notice.[16] In November 2013, a criminal investigation of the disclosure was undertaken by Britain's Metropolitan Police Service.[17] In December 2013, The Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger said: "We have published I think 26 documents so far out of the 58,000 we've seen."[18]

The extent to which the media reports responsibly informed the public is disputed. In January 2014, Obama said that "the sensational way in which these disclosures have come out has often shed more heat than light"[19] and critics such as Sean Wilentz have noted that many of the Snowden documents do not concern domestic surveillance.[20] The US & British Defense establishment weigh the strategic harm in the period following the disclosures more heavily than their civic public benefit. In its first assessment of these disclosures, the Pentagon concluded that Snowden committed the biggest "theft" of U.S. secrets in the history of the United States.[21] Sir David Omand, a former director of GCHQ, described Snowden's disclosure as the "most catastrophic loss to British intelligence ever".[22]

Background

[edit]Snowden obtained the documents while working for Booz Allen Hamilton, one of the largest contractors for defense and intelligence in the United States.[2] The initial simultaneous publication in June 2013 by The Washington Post and The Guardian[23] continued throughout 2013. A small portion of the estimated full cache of documents was later published by other media outlets worldwide, most notably The New York Times (United States), the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Der Spiegel (Germany), O Globo (Brazil), Le Monde (France), L'espresso (Italy), NRC Handelsblad (the Netherlands), Dagbladet (Norway), El País (Spain), and Sveriges Television (Sweden).[24]

Barton Gellman, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who led The Washington Post's coverage of Snowden's disclosures, summarized the leaks as follows:

Taken together, the revelations have brought to light a global surveillance system that cast off many of its historical restraints after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Secret legal authorities empowered the NSA to sweep in the telephone, Internet and location records of whole populations.

The disclosure revealed specific details of the NSA's close cooperation with U.S. federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)[26][27] and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA),[28][29] in addition to the agency's previously undisclosed financial payments to numerous commercial partners and telecommunications companies,[30][31][32] as well as its previously undisclosed relationships with international partners such as Britain,[33][34] France,[10][35] Germany,[3][36] and its secret treaties with foreign governments that were recently established for sharing intercepted data of each other's citizens.[5][37][38][39] The disclosures were made public over the course of several months since June 2013, by the press in several nations from the trove leaked by the former NSA contractor Edward J. Snowden,[40] who obtained the trove while working for Booz Allen Hamilton.[2]

George Brandis, the Attorney-General of Australia, asserted that Snowden's disclosure is the "most serious setback for Western intelligence since the Second World War."[41]

Global surveillance

[edit]As of December 2013[update], global surveillance programs include:

| Program | International contributors and/or partners | Commercial partners |

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

| ||

|

||

| Stateroom | ||

| Lustre |

|

The NSA was also getting data directly from telecommunications companies code-named Artifice (Verizon), Lithium (AT&T), Serenade, SteelKnight, and X. The real identities of the companies behind these code names were not included in the Snowden document dump because they were protected as Exceptionally Controlled Information which prevents wide circulation even to those (like Snowden) who otherwise have the necessary security clearance.[64][65]

Disclosures

[edit]Although the exact size of Snowden's disclosure remains unknown, the following estimates have been put up by various government officials:

- At least 15,000 Australian intelligence files, according to Australian officials[41]

- At least 58,000 British intelligence files, according to British officials[66]

- About 1.7 million U.S. intelligence files, according to U.S. Department of Defense talking points[21][67]

As a contractor of the NSA, Snowden was granted access to U.S. government documents along with top secret documents of several allied governments, via the exclusive Five Eyes network.[68] Snowden claims that he currently does not physically possess any of these documents, having surrendered all copies to journalists he met in Hong Kong.[69]

According to his lawyer, Snowden has pledged not to release any documents while in Russia, leaving the responsibility for further disclosures solely to journalists.[70] As of 2014, the following news outlets have accessed some of the documents provided by Snowden: Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Channel 4, Der Spiegel, El País, El Mundo, L'espresso, Le Monde, NBC, NRC Handelsblad, Dagbladet, O Globo, South China Morning Post, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Sveriges Television, The Guardian, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.

Historical context

[edit]In the 1970s, NSA analyst Perry Fellwock (under the pseudonym "Winslow Peck") revealed the existence of the UKUSA Agreement, which forms the basis of the ECHELON network, whose existence was revealed in 1988 by Lockheed employee Margaret Newsham.[71][72] Months before the September 11 attacks and during its aftermath, further details of the global surveillance apparatus were provided by various individuals such as the former MI5 official David Shayler and the journalist James Bamford,[73][74] who were followed by:

- NSA employees William Binney and Thomas Andrews Drake, who revealed that the NSA is rapidly expanding its surveillance[75][76]

- GCHQ employee Katharine Gun, who revealed a plot to bug UN delegates shortly before the Iraq War[77]

- British Cabinet Minister Clare Short, who revealed in 2004 that the UK had spied on UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan[78]

- NSA employee Russ Tice, who triggered the NSA warrantless surveillance controversy after revealing that the Bush Administration had spied on U.S. citizens without court approval[79][80]

- Journalist Leslie Cauley of USA Today, who revealed in 2006 that the NSA is keeping a massive database of Americans' phone calls[81]

- AT&T employee Mark Klein, who revealed in 2006 the existence of Room 641A of the NSA[82]

- Activists Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning, who revealed in 2011 the existence of the mass surveillance industry[83]

- Journalist Michael Hastings, who revealed in 2012 that protestors of the Occupy Wall Street movement were kept under surveillance[84]

In the aftermath of Snowden's revelations, The Pentagon concluded that Snowden committed the biggest theft of U.S. secrets in the history of the United States.[21] In Australia, the coalition government described the leaks as the most damaging blow dealt to Australian intelligence in history.[41] Sir David Omand, a former director of GCHQ, described Snowden's disclosure as the "most catastrophic loss to British intelligence ever".[22]

Timeline

[edit]

In April 2012, NSA contractor Edward Snowden began downloading documents.[86] That year, Snowden had made his first contact with journalist Glenn Greenwald, then employed by The Guardian, and he contacted documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras in January 2013.[87][88]

2013

[edit]May

[edit]In May 2013, Snowden went on temporary leave from his position at the NSA, citing the pretext of receiving treatment for his epilepsy. Toward the end of May, he traveled to Hong Kong.[89][90] Greenwald, Poitras and The Guardian's defence and intelligence correspondent Ewen MacAskill flew to Hong Kong to meet Snowden.

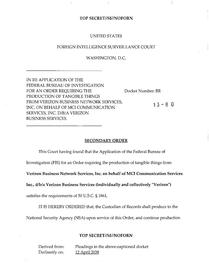

June

[edit]After the U.S.-based editor of The Guardian, Janine Gibson, held several meetings in New York City, she decided that Greenwald, Poitras and the Guardian's defence and intelligence correspondent Ewen MacAskill would fly to Hong Kong to meet Snowden. On June 5, in the first media report based on the leaked material,[91] The Guardian exposed a top secret court order showing that the NSA had collected phone records from over 120 million Verizon subscribers.[92] Under the order, the numbers of both parties on a call, as well as the location data, unique identifiers, time of call, and duration of call were handed over to the FBI, which turned over the records to the NSA.[92] According to The Wall Street Journal, the Verizon order is part of a controversial data program, which seeks to stockpile records on all calls made in the U.S., but does not collect information directly from T-Mobile US and Verizon Wireless, in part because of their foreign ownership ties.[93]

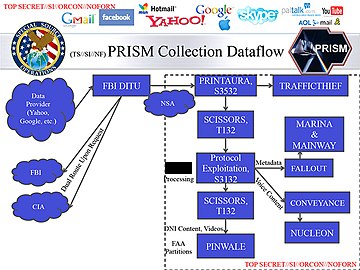

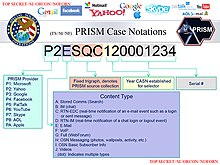

On June 6, 2013, the second media disclosure, the revelation of the PRISM surveillance program (which collects the e-mail, voice, text and video chats of foreigners and an unknown number of Americans from Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Apple and other tech giants),[94][95][96][97] was published simultaneously by The Guardian and The Washington Post.[85][98]

Der Spiegel revealed NSA spying on multiple diplomatic missions of the European Union and the United Nations Headquarters in New York.[99][100] During specific episodes within a four-year period, the NSA hacked several Chinese mobile-phone companies,[101] the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Tsinghua University in Beijing,[102] and the Asian fiber-optic network operator Pacnet.[103] Only Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK are explicitly exempted from NSA attacks, whose main target in the European Union is Germany.[104] A method of bugging encrypted fax machines used at an EU embassy is codenamed Dropmire.[105]

During the 2009 G-20 London summit, the British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) intercepted the communications of foreign diplomats.[106] In addition, GCHQ has been intercepting and storing mass quantities of fiber-optic traffic via Tempora.[107] Two principal components of Tempora are called "Mastering the Internet" (MTI) and "Global Telecoms Exploitation".[108] The data is preserved for three days while metadata is kept for thirty days.[109] Data collected by GCHQ under Tempora is shared with the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States.[108]

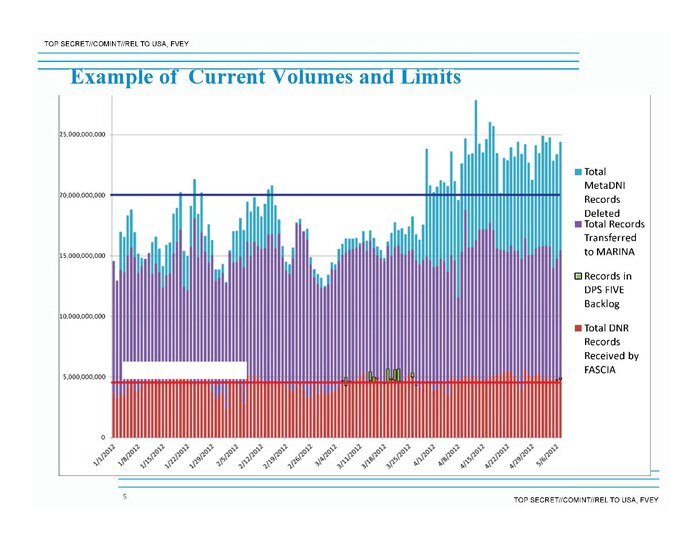

From 2001 to 2011, the NSA collected vast amounts of metadata records detailing the email and internet usage of Americans via Stellar Wind,[110] which was later terminated due to operational and resource constraints. It was subsequently replaced by newer surveillance programs such as ShellTrumpet, which "processed its one trillionth metadata record" by the end of December 2012.[111]

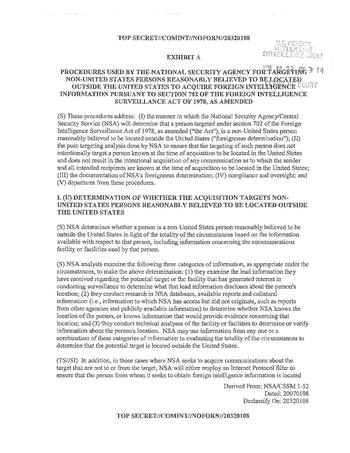

The NSA follows specific procedures to target non-U.S. persons[112] and to minimize data collection from U.S. persons.[113] These court-approved policies allow the NSA to:[114][115]

- keep data that could potentially contain details of U.S. persons for up to five years;

- retain and make use of "inadvertently acquired" domestic communications if they contain usable intelligence, information on criminal activity, threat of harm to people or property, are encrypted, or are believed to contain any information relevant to cybersecurity;

- preserve "foreign intelligence information" contained within attorney–client communications; and

- access the content of communications gathered from "U.S. based machine[s]" or phone numbers in order to establish if targets are located in the U.S., for the purposes of ceasing further surveillance.

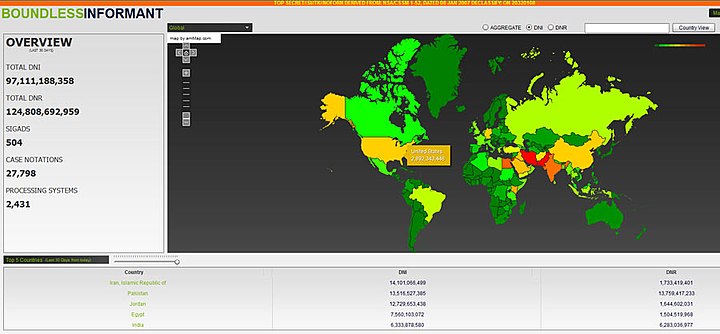

According to Boundless Informant, over 97 billion pieces of intelligence were collected over a 30-day period ending in March 2013. Out of all 97 billion sets of information, about 3 billion data sets originated from U.S. computer networks[116] and around 500 million metadata records were collected from German networks.[117]

In August 2013, it was revealed that the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND) of Germany transfers massive amounts of metadata records to the NSA.[118]

Der Spiegel disclosed that out of all 27 member states of the European Union, Germany is the most targeted due to the NSA's systematic monitoring and storage of Germany's telephone and Internet connection data. According to the magazine the NSA stores data from around half a billion communications connections in Germany each month. This data includes telephone calls, emails, mobile-phone text messages and chat transcripts.[119]

July

[edit]The NSA gained massive amounts of information captured from the monitored data traffic in Europe. For example, in December 2012, the NSA gathered on an average day metadata from some 15 million telephone connections and 10 million Internet datasets. The NSA also monitored the European Commission in Brussels and monitored EU diplomatic Facilities in Washington and at the United Nations by placing bugs in offices as well as infiltrating computer networks.[120]

The U.S. government made as part of its UPSTREAM data collection program deals with companies to ensure that it had access to and hence the capability to surveil undersea fiber-optic cables which deliver e-mails, Web pages, other electronic communications and phone calls from one continent to another at the speed of light.[121][122]

According to the Brazilian newspaper O Globo, the NSA spied on millions of emails and calls of Brazilian citizens,[123][124] while Australia and New Zealand have been involved in the joint operation of the NSA's global analytical system XKeyscore.[125][126] Among the numerous allied facilities contributing to XKeyscore are four installations in Australia and one in New Zealand:

- Pine Gap near Alice Springs, Australia, which is partly operated by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)[126]

- The Shoal Bay Receiving Station near Darwin, Australia, is operated by the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)[126]

- The Australian Defence Satellite Communications Station near Geraldton, Australia, is operated by the ASD[126]

- HMAS Harman outside Canberra, Australia, is operated by the ASD[126]

- Waihopai Station near Blenheim, New Zealand, is operated by New Zealand's Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB)[126]

O Globo released an NSA document titled "Primary FORNSAT Collection Operations", which revealed the specific locations and codenames of the FORNSAT intercept stations in 2002.[127]

According to Edward Snowden, the NSA has established secret intelligence partnerships with many Western governments.[126] The Foreign Affairs Directorate (FAD) of the NSA is responsible for these partnerships, which, according to Snowden, are organized such that foreign governments can "insulate their political leaders" from public outrage in the event that these global surveillance partnerships are leaked.[128]

In an interview published by Der Spiegel, Snowden accused the NSA of being "in bed together with the Germans".[129] The NSA granted the German intelligence agencies BND (foreign intelligence) and BfV (domestic intelligence) access to its controversial XKeyscore system.[130] In return, the BND turned over copies of two systems named Mira4 and Veras, reported to exceed the NSA's SIGINT capabilities in certain areas.[3] Every day, massive amounts of metadata records are collected by the BND and transferred to the NSA via the Bad Aibling Station near Munich, Germany.[3] In December 2012 alone, the BND handed over 500 million metadata records to the NSA.[131][132]

In a document dated January 2013, the NSA acknowledged the efforts of the BND to undermine privacy laws:

The BND has been working to influence the German government to relax interpretation of the privacy laws to provide greater opportunities of intelligence sharing.[132]

According to an NSA document dated April 2013, Germany has now become the NSA's "most prolific partner".[132] Under a section of a separate document leaked by Snowden titled "Success Stories", the NSA acknowledged the efforts of the German government to expand the BND's international data sharing with partners:

The German government modifies its interpretation of the G-10 privacy law ... to afford the BND more flexibility in sharing protected information with foreign partners.[49]

In addition, the German government was well aware of the PRISM surveillance program long before Edward Snowden made details public. According to Angela Merkel's spokesman Steffen Seibert, there are two separate PRISM programs – one is used by the NSA and the other is used by NATO forces in Afghanistan.[133] The two programs are "not identical".[133]

The Guardian revealed further details of the NSA's XKeyscore tool, which allows government analysts to search through vast databases containing emails, online chats and the browsing histories of millions of individuals without prior authorization.[134][135][136] Microsoft "developed a surveillance capability to deal" with the interception of encrypted chats on Outlook.com, within five months after the service went into testing. NSA had access to Outlook.com emails because "Prism collects this data prior to encryption."[45]

In addition, Microsoft worked with the FBI to enable the NSA to gain access to its cloud storage service SkyDrive. An internal NSA document dating from August 3, 2012, described the PRISM surveillance program as a "team sport".[45]

The CIA's National Counterterrorism Center is allowed to examine federal government files for possible criminal behavior, even if there is no reason to suspect U.S. citizens of wrongdoing. Previously the NTC was barred to do so, unless a person was a terror suspect or related to an investigation.[137]

Snowden also confirmed that Stuxnet was cooperatively developed by the United States and Israel.[138] In a report unrelated to Edward Snowden, the French newspaper Le Monde revealed that France's DGSE was also undertaking mass surveillance, which it described as "illegal and outside any serious control".[139][140]

August

[edit]Documents leaked by Edward Snowden that were seen by Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) and Norddeutscher Rundfunk revealed that several telecom operators have played a key role in helping the British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) tap into worldwide fiber-optic communications. The telecom operators are:

- Verizon Business (codenamed "Dacron")[54][141]

- BT (codenamed "Remedy")[54][141]

- Vodafone Cable (codenamed "Gerontic")[54][141]

- Global Crossing (codenamed "Pinnage")[54][141]

- Level 3 (codenamed "Little")[54][141]

- Viatel (codenamed "Vitreous")[54][141]

- Interoute (codenamed "Streetcar")[54][141]

Each of them were assigned a particular area of the international fiber-optic network for which they were individually responsible. The following networks have been infiltrated by GCHQ: TAT-14 (EU-UK-US), Atlantic Crossing 1 (EU-UK-US), Circe South (France-UK), Circe North (Netherlands-UK), Flag Atlantic-1, Flag Europa-Asia, SEA-ME-WE 3 (Southeast Asia-Middle East-Western Europe), SEA-ME-WE 4 (Southeast Asia-Middle East-Western Europe), Solas (Ireland-UK), UK-France 3, UK-Netherlands 14, ULYSSES (EU-UK), Yellow (UK-US) and Pan European Crossing (EU-UK).[142]

Telecommunication companies who participated were "forced" to do so and had "no choice in the matter".[142] Some of the companies were subsequently paid by GCHQ for their participation in the infiltration of the cables.[142] According to the SZ, GCHQ has access to the majority of internet and telephone communications flowing throughout Europe, can listen to phone calls, read emails and text messages, see which websites internet users from all around the world are visiting. It can also retain and analyse nearly the entire European internet traffic.[142]

GCHQ is collecting all data transmitted to and from the United Kingdom and Northern Europe via the undersea fibre optic telecommunications cable SEA-ME-WE 3. The Security and Intelligence Division (SID) of Singapore co-operates with Australia in accessing and sharing communications carried by the SEA-ME-WE-3 cable. The Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) is also in a partnership with British, American and Singaporean intelligence agencies to tap undersea fibre optic telecommunications cables that link Asia, the Middle East and Europe and carry much of Australia's international phone and internet traffic.[143]

The U.S. runs a top-secret surveillance program known as the Special Collection Service (SCS), which is based in over 80 U.S. consulates and embassies worldwide.[144][145] The NSA hacked the United Nations' video conferencing system in Summer 2012 in violation of a UN agreement.[144][145]

The NSA is not just intercepting the communications of Americans who are in direct contact with foreigners targeted overseas, but also searching the contents of vast amounts of e-mail and text communications into and out of the country by Americans who mention information about foreigners under surveillance.[146] It also spied on Al Jazeera and gained access to its internal communications systems.[147]

The NSA has built a surveillance network that has the capacity to reach roughly 75% of all U.S. Internet traffic.[148][149][150] U.S. Law-enforcement agencies use tools used by computer hackers to gather information on suspects.[151][152] An internal NSA audit from May 2012 identified 2776 incidents i.e. violations of the rules or court orders for surveillance of Americans and foreign targets in the U.S. in the period from April 2011 through March 2012, while U.S. officials stressed that any mistakes are not intentional.[153][154][155][156]

The FISA Court that is supposed to provide critical oversight of the U.S. government's vast spying programs has limited ability to do so and it must trust the government to report when it improperly spies on Americans.[157] A legal opinion declassified on August 21, 2013, revealed that the NSA intercepted for three years as many as 56,000 electronic communications a year of Americans not suspected of having links to terrorism, before FISA court that oversees surveillance found the operation unconstitutional in 2011.[158][159][160][161] Under the Corporate Partner Access project, major U.S. telecommunications providers receive hundreds of millions of dollars each year from the NSA.[162] Voluntary cooperation between the NSA and the providers of global communications took off during the 1970s under the cover name BLARNEY.[162]

A letter drafted by the Obama administration specifically to inform Congress of the government's mass collection of Americans' telephone communications data was withheld from lawmakers by leaders of the House Intelligence Committee in the months before a key vote affecting the future of the program.[163][164]

The NSA paid GCHQ over £100 Million between 2009 and 2012, in exchange for these funds GCHQ "must pull its weight and be seen to pull its weight." Documents referenced in the article explain that the weaker British laws regarding spying are "a selling point" for the NSA. GCHQ is also developing the technology to "exploit any mobile phone at any time."[165] The NSA has under a legal authority a secret backdoor into its databases gathered from large Internet companies enabling it to search for U.S. citizens' email and phone calls without a warrant.[166][167]

The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board urged the U.S. intelligence chiefs to draft stronger US surveillance guidelines on domestic spying after finding that several of those guidelines have not been updated up to 30 years.[168][169] U.S. intelligence analysts have deliberately broken rules designed to prevent them from spying on Americans by choosing to ignore so-called "minimisation procedures" aimed at protecting privacy[170][171] and used the NSA's agency's enormous eavesdropping power to spy on love interests.[172]

After the U.S. Foreign Secret Intelligence Court ruled in October 2011 that some of the NSA's activities were unconstitutional, the agency paid millions of dollars to major internet companies to cover extra costs incurred in their involvement with the PRISM surveillance program.[173]

"Mastering the Internet" (MTI) is part of the Interception Modernisation Programme (IMP) of the British government that involves the insertion of thousands of DPI (deep packet inspection) "black boxes" at various internet service providers, as revealed by the British media in 2009.[174]

In 2013, it was further revealed that the NSA had made a £17.2 million financial contribution to the project, which is capable of vacuuming signals from up to 200 fibre-optic cables at all physical points of entry into Great Britain.[175]

September

[edit]The Guardian and The New York Times reported on secret documents leaked by Snowden showing that the NSA has been in "collaboration with technology companies" as part of "an aggressive, multipronged effort" to weaken the encryption used in commercial software, and GCHQ has a team dedicated to cracking "Hotmail, Google, Yahoo and Facebook" traffic.[182]

Germany's domestic security agency Bundesverfassungsschutz (BfV) systematically transfers the personal data of German residents to the NSA, CIA and seven other members of the United States Intelligence Community, in exchange for information and espionage software.[183][184][185] Israel, Sweden and Italy are also cooperating with American and British intelligence agencies. Under a secret treaty codenamed "Lustre", French intelligence agencies transferred millions of metadata records to the NSA.[62][63][186][187]

The Obama Administration secretly won permission from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court in 2011 to reverse restrictions on the National Security Agency's use of intercepted phone calls and e-mails, permitting the agency to search deliberately for Americans' communications in its massive databases. The searches take place under a surveillance program Congress authorized in 2008 under Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Under that law, the target must be a foreigner "reasonably believed" to be outside the United States, and the court must approve the targeting procedures in an order good for one year. But a warrant for each target would thus no longer be required. That means that communications with Americans could be picked up without a court first determining that there is probable cause that the people they were talking to were terrorists, spies or "foreign powers." The FISC extended the length of time that the NSA is allowed to retain intercepted U.S. communications from five years to six years with an extension possible for foreign intelligence or counterintelligence purposes. Both measures were done without public debate or any specific authority from Congress.[188]

A special branch of the NSA called "Follow the Money" (FTM) monitors international payments, banking and credit card transactions and later stores the collected data in the NSA's own financial databank "Tracfin".[189] The NSA monitored the communications of Brazil's president Dilma Rousseff and her top aides.[190] The agency also spied on Brazil's oil firm Petrobras as well as French diplomats, and gained access to the private network of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of France and the SWIFT network.[191]

In the United States, the NSA uses the analysis of phone call and e-mail logs of American citizens to create sophisticated graphs of their social connections that can identify their associates, their locations at certain times, their traveling companions and other personal information.[192] The NSA routinely shares raw intelligence data with Israel without first sifting it to remove information about U.S. citizens.[5][193]

In an effort codenamed GENIE, computer specialists can control foreign computer networks using "covert implants," a form of remotely transmitted malware on tens of thousands of devices annually.[194][195][196][197] As worldwide sales of smartphones began exceeding those of feature phones, the NSA decided to take advantage of the smartphone boom. This is particularly advantageous because the smartphone combines a myriad of data that would interest an intelligence agency, such as social contacts, user behavior, interests, location, photos and credit card numbers and passwords.[198]

An internal NSA report from 2010 stated that the spread of the smartphone has been occurring "extremely rapidly"—developments that "certainly complicate traditional target analysis."[198] According to the document, the NSA has set up task forces assigned to several smartphone manufacturers and operating systems, including Apple Inc.'s iPhone and iOS operating system, as well as Google's Android mobile operating system.[198] Similarly, Britain's GCHQ assigned a team to study and crack the BlackBerry.[198]

Under the heading "iPhone capability", the document notes that there are smaller NSA programs, known as "scripts", that can perform surveillance on 38 different features of the iOS 3 and iOS 4 operating systems. These include the mapping feature, voicemail and photos, as well as Google Earth, Facebook and Yahoo! Messenger.[198]

On September 9, 2013, an internal NSA presentation on iPhone Location Services was published by Der Spiegel. One slide shows scenes from Apple's 1984-themed television commercial alongside the words "Who knew in 1984..."; another shows Steve Jobs holding an iPhone, with the text "...that this would be big brother..."; and a third shows happy consumers with their iPhones, completing the question with "...and the zombies would be paying customers?"[199]

October

[edit]On October 4, 2013, The Washington Post and The Guardian jointly reported that the NSA and GCHQ had made repeated attempts to spy on anonymous Internet users who have been communicating in secret via the anonymity network Tor. Several of these surveillance operations involved the implantation of malicious code into the computers of Tor users who visit particular websites. The NSA and GCHQ had partly succeeded in blocking access to the anonymous network, diverting Tor users to insecure channels. The government agencies were also able to uncover the identity of some anonymous Internet users.[200][201][202][203]

The Communications Security Establishment (CSE) has been using a program called Olympia to map the communications of Brazil's Mines and Energy Ministry by targeting the metadata of phone calls and emails to and from the ministry.[204][205]

The Australian Federal Government knew about the PRISM surveillance program months before Edward Snowden made details public.[206][207]

The NSA gathered hundreds of millions of contact lists from personal e-mail and instant messaging accounts around the world. The agency did not target individuals. Instead it collected contact lists in large numbers that amount to a sizable fraction of the world's e-mail and instant messaging accounts. Analysis of that data enables the agency to search for hidden connections and to map relationships within a much smaller universe of foreign intelligence targets.[208][209][210][211]

The NSA monitored the public email account of former Mexican president Felipe Calderón (thus gaining access to the communications of high-ranking cabinet members), the emails of several high-ranking members of Mexico's security forces and text and the mobile phone communication of current Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto.[212][213] The NSA tries to gather cellular and landline phone numbers—often obtained from American diplomats—for as many foreign officials as possible. The contents of the phone calls are stored in computer databases that can regularly be searched using keywords.[214][215]

The NSA has been monitoring telephone conversations of 35 world leaders.[216] The U.S. government's first public acknowledgment that it tapped the phones of world leaders was reported on October 28, 2013, by the Wall Street Journal after an internal U.S. government review turned up NSA monitoring of some 35 world leaders.[217] GCHQ has tried to keep its mass surveillance program a secret because it feared a "damaging public debate" on the scale of its activities which could lead to legal challenges against them.[218]

The Guardian revealed that the NSA had been monitoring telephone conversations of 35 world leaders after being given the numbers by an official in another U.S. government department. A confidential memo revealed that the NSA encouraged senior officials in such Departments as the White House, State and The Pentagon, to share their "Rolodexes" so the agency could add the telephone numbers of leading foreign politicians to their surveillance systems. Reacting to the news, German leader Angela Merkel, arriving in Brussels for an EU summit, accused the U.S. of a breach of trust, saying: "We need to have trust in our allies and partners, and this must now be established once again. I repeat that spying among friends is not at all acceptable against anyone, and that goes for every citizen in Germany."[216] The NSA collected in 2010 data on ordinary Americans' cellphone locations, but later discontinued it because it had no "operational value."[219]

Under Britain's MUSCULAR programme, the NSA and GCHQ have secretly broken into the main communications links that connect Yahoo and Google data centers around the world and thereby gained the ability to collect metadata and content at will from hundreds of millions of user accounts.[220][221][222][223]

The mobile phone of German Chancellor Angela Merkel might have been tapped by U.S. intelligence.[224][225][226][227] According to the Spiegel this monitoring goes back to 2002[228][229] and ended in the summer of 2013,[217] while The New York Times reported that Germany has evidence that the NSA's surveillance of Merkel began during George W. Bush's tenure.[230] After learning from Der Spiegel magazine that the NSA has been listening in to her personal mobile phone, Merkel compared the snooping practices of the NSA with those of the Stasi.[231] It was reported in March 2014, by Der Spiegel that Merkel had also been placed on an NSA surveillance list alongside 122 other world leaders.[232]

On October 31, 2013, Hans-Christian Ströbele, a member of the German Bundestag who visited Snowden in Russia, reported on Snowden's willingness to provide details of the NSA's espionage program.[233]

A highly sensitive signals intelligence collection program known as Stateroom involves the interception of radio, telecommunications and internet traffic. It is operated out of the diplomatic missions of the Five Eyes (Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, United States) in numerous locations around the world. The program conducted at U.S. diplomatic missions is run in concert by the U.S. intelligence agencies NSA and CIA in a joint venture group called "Special Collection Service" (SCS), whose members work undercover in shielded areas of the American Embassies and Consulates, where they are officially accredited as diplomats and as such enjoy special privileges. Under diplomatic protection, they are able to look and listen unhindered. The SCS for example used the American Embassy near the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin to monitor communications in Germany's government district with its parliament and the seat of the government.[227][234][235][236]

Under the Stateroom surveillance programme, Australia operates clandestine surveillance facilities to intercept phone calls and data across much of Asia.[235][237]

In France, the NSA targeted people belonging to the worlds of business, politics or French state administration. The NSA monitored and recorded the content of telephone communications and the history of the connections of each target i.e. the metadata.[238][239] The actual surveillance operation was performed by French intelligence agencies on behalf of the NSA.[62][240] The cooperation between France and the NSA was confirmed by the Director of the NSA, Keith B. Alexander, who asserted that foreign intelligence services collected phone records in "war zones" and "other areas outside their borders" and provided them to the NSA.[241]

The French newspaper Le Monde also disclosed new PRISM and Upstream slides (See Page 4, 7 and 8) coming from the "PRISM/US-984XN Overview" presentation.[242]

In Spain, the NSA intercepted the telephone conversations, text messages and emails of millions of Spaniards, and spied on members of the Spanish government.[243] Between December 10, 2012, and January 8, 2013, the NSA collected metadata on 60 million telephone calls in Spain.[244]

According to documents leaked by Snowden, the surveillance of Spanish citizens was jointly conducted by the NSA and the intelligence agencies of Spain.[245][246]

November

[edit]The New York Times reported that the NSA carries out an eavesdropping effort, dubbed Operation Dreadnought, against the Iranian leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. During his 2009 visit to Iranian Kurdistan, the agency collaborated with GCHQ and the U.S.'s National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, collecting radio transmissions between aircraft and airports, examining Khamenei's convoy with satellite imagery, and enumerating military radar stations. According to the story, an objective of the operation is "communications fingerprinting": the ability to distinguish Khamenei's communications from those of other people in Iran.[247]

The same story revealed an operation code-named Ironavenger, in which the NSA intercepted e-mails sent between a country allied with the United States and the government of "an adversary". The ally was conducting a spear-phishing attack: its e-mails contained malware. The NSA gathered documents and login credentials belonging to the enemy country, along with knowledge of the ally's capabilities for attacking computers.[247]

According to the British newspaper The Independent, the British intelligence agency GCHQ maintains a listening post on the roof of the British Embassy in Berlin that is capable of intercepting mobile phone calls, wi-fi data and long-distance communications all over the German capital, including adjacent government buildings such as the Reichstag (seat of the German parliament) and the Chancellery (seat of Germany's head of government) clustered around the Brandenburg Gate.[248]

Operating under the code-name "Quantum Insert", GCHQ set up a fake website masquerading as LinkedIn, a social website used for professional networking, as part of its efforts to install surveillance software on the computers of the telecommunications operator Belgacom.[249][250][251] In addition, the headquarters of the oil cartel OPEC were infiltrated by GCHQ as well as the NSA, which bugged the computers of nine OPEC employees and monitored the General Secretary of OPEC.[249]

For more than three years GCHQ has been using an automated monitoring system code-named "Royal Concierge" to infiltrate the reservation systems of at least 350 prestigious hotels in many different parts of the world in order to target, search and analyze reservations to detect diplomats and government officials.[252] First tested in 2010, the aim of the "Royal Concierge" is to track down the travel plans of diplomats, and it is often supplemented with surveillance methods related to human intelligence (HUMINT). Other covert operations include the wiretapping of room telephones and fax machines used in targeted hotels as well as the monitoring of computers hooked up to the hotel network.[252]

In November 2013, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and The Guardian revealed that the Australian Signals Directorate (DSD) had attempted to listen to the private phone calls of the president of Indonesia and his wife. The Indonesian foreign minister, Marty Natalegawa, confirmed that he and the president had contacted the ambassador in Canberra. Natalegawa said any tapping of Indonesian politicians' personal phones "violates every single decent and legal instrument I can think of—national in Indonesia, national in Australia, international as well".[253]

Other high-ranking Indonesian politicians targeted by the DSD include:

- Boediono[254] (Vice President)

- Jusuf Kalla[254] (Former Vice President)

- Dino Patti Djalal[254] (Ambassador to the United States)

- Andi Mallarangeng[254] (Government spokesperson)

- Hatta Rajasa[254] (State Secretary)

- Sri Mulyani Indrawati[254] (Former Finance Minister and current managing director of the World Bank)

- Widodo Adi Sutjipto[254] (Former Commander-in-Chief of the military)

- Sofyan Djalil[254] (Senior government advisor)

Carrying the title "3G impact and update", a classified presentation leaked by Snowden revealed the attempts of the ASD/DSD to keep up to pace with the rollout of 3G technology in Indonesia and across Southeast Asia. The ASD/DSD motto placed at the bottom of each page reads: "Reveal their secrets—protect our own."[254]

Under a secret deal approved by British intelligence officials, the NSA has been storing and analyzing the internet and email records of British citizens since 2007. The NSA also proposed in 2005 a procedure for spying on the citizens of the UK and other Five-Eyes nations alliance, even where the partner government has explicitly denied the U.S. permission to do so. Under the proposal, partner countries must neither be informed about this particular type of surveillance, nor the procedure of doing so.[37]

Toward the end of November, The New York Times released an internal NSA report outlining the agency's efforts to expand its surveillance abilities.[255] The five-page document asserts that the law of the United States has not kept up with the needs of the NSA to conduct mass surveillance in the "golden age" of signals intelligence, but there are grounds for optimism because, in the NSA's own words:

The culture of compliance, which has allowed the American people to entrust NSA with extraordinary authorities, will not be compromised in the face of so many demands, even as we aggressively pursue legal authorities...[256]

The report, titled "SIGINT Strategy 2012–2016", also said that the U.S. will try to influence the "global commercial encryption market" through "commercial relationships", and emphasized the need to "revolutionize" the analysis of its vast data collection to "radically increase operational impact".[255]

On November 23, 2013, the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad reported that the Netherlands was targeted by U.S. intelligence agencies in the immediate aftermath of World War II. This period of surveillance lasted from 1946 to 1968, and also included the interception of the communications of other European countries including Belgium, France, West Germany and Norway.[257] The Dutch Newspaper also reported that NSA infected more than 50,000 computer networks worldwide, often covertly, with malicious spy software, sometimes in cooperation with local authorities, designed to steal sensitive information.[40][258]

December

[edit]According to the classified documents leaked by Snowden, the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), formerly known as the Defense Signals Directorate, had offered to share intelligence information it had collected with the other intelligence agencies of the UKUSA Agreement. Data shared with foreign countries include "bulk, unselected, unminimized metadata" it had collected. The ASD provided such information on the condition that no Australian citizens were targeted. At the time the ASD assessed that "unintentional collection [of metadata of Australian nationals] is not viewed as a significant issue". If a target was later identified as being an Australian national, the ASD was required to be contacted to ensure that a warrant could be sought. Consideration was given as to whether "medical, legal or religious information" would be automatically treated differently to other types of data, however a decision was made that each agency would make such determinations on a case-by-case basis.[259] Leaked material does not specify where the ASD had collected the intelligence information from, however Section 7(a) of the Intelligence Services Act 2001 (Commonwealth) states that the ASD's role is "...to obtain intelligence about the capabilities, intentions or activities of people or organizations outside Australia...".[260] As such, it is possible ASD's metadata intelligence holdings was focused on foreign intelligence collection and was within the bounds of Australian law.

The Washington Post revealed that the NSA has been tracking the locations of mobile phones from all over the world by tapping into the cables that connect mobile networks globally and that serve U.S. cellphones as well as foreign ones. In the process of doing so, the NSA collects more than five billion records of phone locations on a daily basis. This enables NSA analysts to map cellphone owners' relationships by correlating their patterns of movement over time with thousands or millions of other phone users who cross their paths.[261][262][263][264]

The Washington Post also reported that both GCHQ and the NSA make use of location data and advertising tracking files generated through normal internet browsing (with cookies operated by Google, known as "Pref") to pinpoint targets for government hacking and to bolster surveillance.[265][266][267]

The Norwegian Intelligence Service (NIS), which cooperates with the NSA, has gained access to Russian targets in the Kola Peninsula and other civilian targets. In general, the NIS provides information to the NSA about "Politicians", "Energy" and "Armament".[268] A top secret memo of the NSA lists the following years as milestones of the Norway–United States of America SIGINT agreement, or NORUS Agreement:

- 1952 – Informal starting year of cooperation between the NIS and the NSA[269]

- 1954 – Formalization of the agreement[269]

- 1963 – Extension of the agreement for coverage of foreign instrumentation signals intelligence (FISINT)[269]

- 1970 – Extension of the agreement for coverage of electronic intelligence (ELINT)[269]

- 1994 – Extension of the agreement for coverage of communications intelligence (COMINT)[269]

The NSA considers the NIS to be one of its most reliable partners. Both agencies also cooperate to crack the encryption systems of mutual targets. According to the NSA, Norway has made no objections to its requests from the NIS.[269]

On December 5, Sveriges Television reported the National Defense Radio Establishment (FRA) has been conducting a clandestine surveillance operation in Sweden, targeting the internal politics of Russia. The operation was conducted on behalf of the NSA, receiving data handed over to it by the FRA.[270][271] The Swedish-American surveillance operation also targeted Russian energy interests as well as the Baltic states.[272] As part of the UKUSA Agreement, a secret treaty was signed in 1954 by Sweden with the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, regarding collaboration and intelligence sharing.[273]

As a result of Snowden's disclosures, the notion of Swedish neutrality in international politics was called into question.[274] In an internal document dating from the year 2006, the NSA acknowledged that its "relationship" with Sweden is "protected at the TOP SECRET level because of that nation's political neutrality."[275] Specific details of Sweden's cooperation with members of the UKUSA Agreement include:

- The FRA has been granted access to XKeyscore, an analytical database of the NSA.[276]

- Sweden updated the NSA on changes in Swedish legislation that provided the legal framework for information sharing between the FRA and the Swedish Security Service.[51]

- Since January 2013, a counterterrorism analyst of the NSA has been stationed in the Swedish capital of Stockholm[51]

- The NSA, GCHQ and the FRA signed an agreement in 2004 that allows the FRA to directly collaborate with the NSA without having to consult GCHQ.[51] About five years later, the Riksdag passed a controversial legislative change, briefly allowing the FRA to monitor both wireless and cable bound signals passing the Swedish border without a court order,[277] while also introducing several provisions designed to protect the privacy of individuals, according to the original proposal.[278] This legislation was amended 11 months later,[279] in an effort to strengthen protection of privacy by making court orders a requirement, and by imposing several limits on the intelligence-gathering.[280][281][282]

According to documents leaked by Snowden, the Special Source Operations of the NSA has been sharing information containing "logins, cookies, and GooglePREFID" with the Tailored Access Operations division of the NSA, as well as Britain's GCHQ agency.[283]

During the 2010 G-20 Toronto summit, the U.S. embassy in Ottawa was transformed into a security command post during a six-day spying operation that was conducted by the NSA and closely coordinated with the Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC). The goal of the spying operation was, among others, to obtain information on international development, banking reform, and to counter trade protectionism to support "U.S. policy goals."[284] On behalf of the NSA, the CSEC has set up covert spying posts in 20 countries around the world.[8]

In Italy the Special Collection Service of the NSA maintains two separate surveillance posts in Rome and Milan.[285] According to a secret NSA memo dated September 2010, the Italian embassy in Washington, D.C. has been targeted by two spy operations of the NSA:

- Under the codename "Bruneau", which refers to mission "Lifesaver", the NSA sucks out all the information stored in the embassy's computers and creates electronic images of hard disk drives.[285]

- Under the codename "Hemlock", which refers to mission "Highlands", the NSA gains access to the embassy's communications through physical "implants".[285]

Due to concerns that terrorist or criminal networks may be secretly communicating via computer games, the NSA, GCHQ, CIA, and FBI have been conducting surveillance and scooping up data from the networks of many online games, including massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) such as World of Warcraft, as well as virtual worlds such as Second Life, and the Xbox gaming console.[286][287][288][289]

The NSA has cracked the most commonly used cellphone encryption technology, A5/1. According to a classified document leaked by Snowden, the agency can "process encrypted A5/1" even when it has not acquired an encryption key.[290] In addition, the NSA uses various types of cellphone infrastructure, such as the links between carrier networks, to determine the location of a cellphone user tracked by Visitor Location Registers.[291]

US district court judge for the District of Columbia, Richard Leon, declared[292][293][294][295] on December 16, 2013, that the mass collection of metadata of Americans' telephone records by the National Security Agency probably violates the fourth amendment prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures.[296] Leon granted the request for a preliminary injunction that blocks the collection of phone data for two private plaintiffs (Larry Klayman, a conservative lawyer, and Charles Strange, father of a cryptologist killed in Afghanistan when his helicopter was shot down in 2011)[297] and ordered the government to destroy any of their records that have been gathered. But the judge stayed action on his ruling pending a government appeal, recognizing in his 68-page opinion the "significant national security interests at stake in this case and the novelty of the constitutional issues."[296]

However federal judge William H. Pauley III in New York City ruled[298] the U.S. government's global telephone data-gathering system is needed to thwart potential terrorist attacks, and that it can only work if everyone's calls are swept in. U.S. District Judge Pauley also ruled that Congress legally set up the program and that it does not violate anyone's constitutional rights. The judge also concluded that the telephone data being swept up by NSA did not belong to telephone users, but to the telephone companies. He further ruled that when NSA obtains such data from the telephone companies, and then probes into it to find links between callers and potential terrorists, this further use of the data was not even a search under the Fourth Amendment. He also concluded that the controlling precedent is Smith v. Maryland: "Smith's bedrock holding is that an individual has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information provided to third parties," Judge Pauley wrote.[299][300][301][302] The American Civil Liberties Union declared on January 2, 2012, that it will appeal Judge Pauley's ruling that NSA bulk the phone record collection is legal. "The government has a legitimate interest in tracking the associations of suspected terrorists, but tracking those associations does not require the government to subject every citizen to permanent surveillance," deputy ACLU legal director Jameel Jaffer said in a statement.[303]

In recent years, American and British intelligence agencies conducted surveillance on more than 1,100 targets, including the office of an Israeli prime minister, heads of international aid organizations, foreign energy companies and a European Union official involved in antitrust battles with American technology businesses.[304]

A catalog of high-tech gadgets and software developed by the NSA's Tailored Access Operations (TAO) was leaked by the German news magazine Der Spiegel.[305] Dating from 2008, the catalog revealed the existence of special gadgets modified to capture computer screenshots and USB flash drives secretly fitted with radio transmitters to broadcast stolen data over the airwaves, and fake base stations intended to intercept mobile phone signals, as well as many other secret devices and software implants listed here:

-

SPARROW II – Mobile device that functions as a WLAN collection system

-

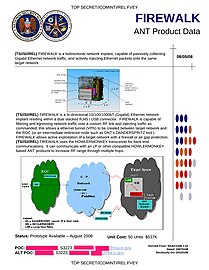

FIREWALK – Hardware implant for collection of Gigabit Ethernet network traffic

-

GINSU – Software that extends application persistence for the CNE (Computer Network Exploitation) implant KONGUR

-

IRATEMONK – Replaces master boot records (MBRs) of various hard disk manufacturers

-

WISTFULTOLL – Software implant that exploits Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) to transfer data

-

HOWLERMONKEY – Short to medium range radio frequency (RF) transceiver

-

NIGHTSTAND – Mobile device that introduces NSA software to computers up to 8 mi (13 km) away via wireless LAN

-

COTTONMOUTH-I – USB flash drive implant

-

COTTONMOUTH-II – USB implant

-

COTTONMOUTH-III – USB implant

-

JUNIORMINT – Digital core packaged into a printed circuit board (PCB) and a flip chip

-

MAESTRO-II – Miniaturized digital core packaged into a multi-chip module (MCM)

-

TRINITY – Miniaturized digital core packaged into a multi-chip module (MCM)

-

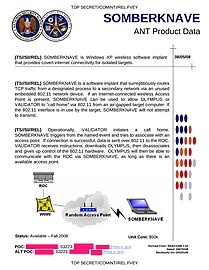

SOMBERKNAVE – Software implant for Windows XP that provides covert Internet access for the NSA's targets

-

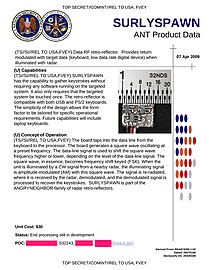

SURLYSPAWN – Device for keystroke logging

-

RAGEMASTER – Hardware implant concealed in a computer's VGA cable to capture screenshots and video

-

IRONCHEF – Software implant that functions as a permanent BIOS system

-

DEITYBOUNCE – Software implant for insertion into Dell PowerEdge servers

-

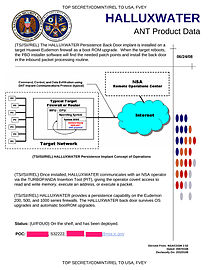

HALLUXWATER – Installs a backdoor targeting Huawei's Eudemon firewalls

-

FEEDTROUGH – Installs a backdoor targeting numerous Juniper Networks firewalls

-

GOURMETTROUGH – Installs a backdoor targeting numerous Juniper Networks firewalls

-

LOUDAUTO – Covert listening device

-

NIGHTWATCH – Device for reconstruction of signals belonging to target systems

-

CTX4000 – Portable continuous-wave radar (CRW) unit to illuminate a target system for Dropmire collection

-

PHOTOANGLO – Successor to the CTX4000, jointly developed by the NSA and GCHQ

-

TAWDRYYARD – Device that functions as a radio frequency (RF) retroreflector

-

PICASSO – Modified GSM handset

-

GENESIS – Modified Motorola SLVR L9 handset

-

CROSSBEAM – GSM module for commercial mobile phones

-

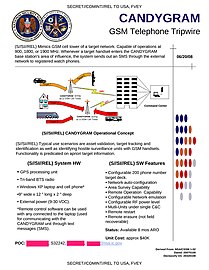

CANDYGRAM – Mimics the GSM cell tower of targeted networks

-

GOPHERSET – Software implant for GSM subscriber identity module (SIM) cards that pulls out address books, SMS (Short Message Service) text messages, and call log information

-

MONKEYCALENDAR – Software implant for GSM subscriber identity module (SIM) cards that pulls out geolocation information

-

TOTECHASER – Windows CE implant that targets the Thuraya handset

-

TOTEGHOSTLY 2.0 – Software implant for Windows Mobile capable of retrieving SMS (Short Message Service) text messages, Voicemail and contact lists, as well as turning on built-in microphones and cameras

The Tailored Access Operations (TAO) division of the NSA intercepted the shipping deliveries of computers and laptops in order to install spyware and physical implants on electronic gadgets. This was done in close cooperation with the FBI and the CIA.[305][306][307][308] NSA officials responded to the Spiegel reports with a statement, which said: "Tailored Access Operations is a unique national asset that is on the front lines of enabling NSA to defend the nation and its allies. [TAO's] work is centred on computer network exploitation in support of foreign intelligence collection."[309]

In a separate disclosure unrelated to Snowden, the French Trésor public, which runs a certificate authority, was found to have issued fake certificates impersonating Google in order to facilitate spying on French government employees via man-in-the-middle attacks.[310]

2014

[edit]January

[edit]The NSA is working to build a powerful quantum computer capable of breaking all types of encryption.[313][314][315][316][317] The effort is part of a US$79.7 million research program known as "Penetrating Hard Targets". It involves extensive research carried out in large, shielded rooms known as Faraday cages, which are designed to prevent electromagnetic radiation from entering or leaving.[314] Currently, the NSA is close to producing basic building blocks that will allow the agency to gain "complete quantum control on two semiconductor qubits".[314] Once a quantum computer is successfully built, it would enable the NSA to unlock the encryption that protects data held by banks, credit card companies, retailers, brokerages, governments and health care providers.[313]

According to The New York Times, the NSA is monitoring approximately 100,000 computers worldwide with spy software named Quantum. Quantum enables the NSA to conduct surveillance on those computers on the one hand, and can also create a digital highway for launching cyberattacks on the other hand. Among the targets are the Chinese and Russian military, but also trade institutions within the European Union. The NYT also reported that the NSA can access and alter computers which are not connected with the internet by a secret technology in use by the NSA since 2008. The prerequisite is the physical insertion of the radio frequency hardware by a spy, a manufacturer or an unwitting user. The technology relies on a covert channel of radio waves that can be transmitted from tiny circuit boards and USB cards inserted surreptitiously into the computers. In some cases, they are sent to a briefcase-size relay station that intelligence agencies can set up miles away from the target. The technology can also transmit malware back to the infected computer.[40]

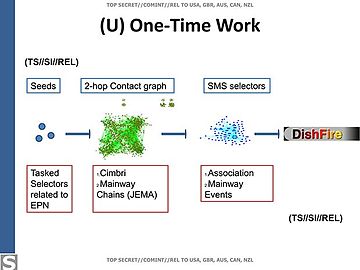

Channel 4 and The Guardian revealed the existence of Dishfire, a massive database of the NSA that collects hundreds of millions of text messages on a daily basis.[318] GCHQ has been given full access to the database, which it uses to obtain personal information of Britons by exploiting a legal loophole.[319]

Each day, the database receives and stores the following amounts of data:

- Geolocation data of more than 76,000 text messages and other travel information[320]

- Over 110,000 names, gathered from electronic business cards[320]

- Over 800,000 financial transactions that are either gathered from text-to-text payments or by linking credit cards to phone users[320]

- Details of 1.6 million border crossings based on the interception of network roaming alerts[320]

- Over 5 million missed call alerts[320]

- About 200 million text messages from around the world[318]

The database is supplemented with an analytical tool known as the Prefer program, which processes SMS messages to extract other types of information including contacts from missed call alerts.[320]

The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board report on mass surveillance was released on January 23, 2014. It recommends to end the bulk telephone metadata, i.e., bulk phone records – phone numbers dialed, call times and durations, but not call content collection – collection program, to create a "Special Advocate" to be involved in some cases before the FISA court judge and to release future and past FISC decisions "that involve novel interpretations of FISA or other significant questions of law, technology or compliance."[321][322][323]

According to a joint disclosure by The New York Times, The Guardian, and ProPublica,[324][325][326][327] the NSA and GCHQ have begun working together to collect and store data from dozens of smartphone application software by 2007 at the latest. A 2008 GCHQ report, leaked by Snowden asserts that "anyone using Google Maps on a smartphone is working in support of a GCHQ system". The NSA and GCHQ have traded recipes for various purposes such as grabbing location data and journey plans that are made when a target uses Google Maps, and vacuuming up address books, buddy lists, phone logs and geographic data embedded in photos posted on the mobile versions of numerous social networks such as Facebook, Flickr, LinkedIn, Twitter, and other services. In a separate 20-page report dated 2012, GCHQ cited the popular smartphone game "Angry Birds" as an example of how an application could be used to extract user data. Taken together, such forms of data collection would allow the agencies to collect vital information about a user's life, including his or her home country, current location (through geolocation), age, gender, ZIP code, marital status, income, ethnicity, sexual orientation, education level, number of children, etc.[328][329]

A GCHQ document dated August 2012 provided details of the Squeaky Dolphin surveillance program, which enables GCHQ to conduct broad, real-time monitoring of various social media features and social media traffic such as YouTube video views, the Like button on Facebook, and Blogspot/Blogger visits without the knowledge or consent of the companies providing those social media features. The agency's "Squeaky Dolphin" program can collect, analyze and utilize YouTube, Facebook and Blogger data in specific situations in real time for analysis purposes. The program also collects the addresses from the billions of videos watched daily as well as some user information for analysis purposes.[330][331][332]

During the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, the NSA and its Five Eyes partners monitored the communications of delegates of numerous countries. This was done to give their own policymakers a negotiating advantage.[333][334]

The Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) has been tracking Canadian air passengers via free Wi-Fi services at a major Canadian airport. Passengers who exited the airport terminal continued to be tracked as they showed up at other Wi-Fi locations across Canada. In a CSEC document dated May 2012, the agency described how it had gained access to two communications systems with over 300,000 users in order to pinpoint a specific imaginary target. The operation was executed on behalf of the NSA as a trial run to test a new technology capable of tracking down "any target that makes occasional forays into other cities/regions." This technology was subsequently shared with Canada's Five Eyes partners – Australia, New Zealand, Britain, and the United States.[335][336][337][338]

February

[edit]According to research by Süddeutsche Zeitung and TV network NDR the mobile phone of former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder was monitored from 2002 onward, reportedly because of his government's opposition to military intervention in Iraq. The source of the latest information is a document leaked by Edward Snowden. The document, containing information about the National Sigint Requirement List (NSRL), had previously been interpreted as referring only to Angela Merkel's mobile. However, Süddeutsche Zeitung and NDR claim to have confirmation from NSA insiders that the surveillance authorisation pertains not to the individual, but the political post – which in 2002 was still held by Schröder. According to research by the two media outlets, Schröder was placed as number 388 on the list, which contains the names of persons and institutions to be put under surveillance by the NSA.[339][340][341][342]

GCHQ launched a cyber-attack on the activist network "Anonymous", using denial-of-service attack (DoS) to shut down a chatroom frequented by the network's members and to spy on them. The attack, dubbed Rolling Thunder, was conducted by a GCHQ unit known as the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG). The unit successfully uncovered the true identities of several Anonymous members.[343][344][345][346]

The NSA Section 215 bulk telephony metadata program which seeks to stockpile records on all calls made in the U.S. is collecting less than 30 percent of all Americans' call records because of an inability to keep pace with the explosion in cellphone use, according to The Washington Post. The controversial program permits the NSA after a warrant granted by the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to record numbers, length and location of every call from the participating carriers.[347][348]

The Intercept reported that the U.S. government is using primarily NSA surveillance to target people for drone strikes overseas. In its report The Intercept author detail the flawed methods which are used to locate targets for lethal drone strikes, resulting in the deaths of innocent people.[349] According to the Washington Post NSA analysts and collectors i.e. NSA personnel which controls electronic surveillance equipment use the NSA's sophisticated surveillance capabilities to track individual targets geographically and in real time, while drones and tactical units aimed their weaponry against those targets to take them out.[350]

An unnamed US law firm, reported to be Mayer Brown, was targeted by Australia's ASD. According to Snowden's documents, the ASD had offered to hand over these intercepted communications to the NSA. This allowed government authorities to be "able to continue to cover the talks, providing highly useful intelligence for interested US customers".[351][352]

NSA and GCHQ documents revealed that the anti-secrecy organization WikiLeaks and other activist groups were targeted for government surveillance and criminal prosecution. In particular, the IP addresses of visitors to WikiLeaks were collected in real time, and the US government urged its allies to file criminal charges against the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, due to his organization's publication of the Afghanistan war logs. The WikiLeaks organization was designated as a "malicious foreign actor".[353]

Quoting an unnamed NSA official in Germany, Bild am Sonntag reported that while President Obama's order to stop spying on Merkel was being obeyed, the focus had shifted to bugging other leading government and business figures including Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere, a close confidant of Merkel. Caitlin Hayden, a security adviser to President Obama, was quoted in the newspaper report as saying, "The US has made clear it gathers intelligence in exactly the same way as any other states."[354][355]

The Intercept reveals that government agencies are infiltrating online communities and engaging in "false flag operations" to discredit targets among them people who have nothing to do with terrorism or national security threats. The two main tactics that are currently used are the injection of all sorts of false material onto the internet in order to destroy the reputation of its targets; and the use of social sciences and other techniques to manipulate online discourse and activism to generate outcomes it considers desirable.[356][357][358][359]

The Guardian reported that Britain's surveillance agency GCHQ, with aid from the National Security Agency, intercepted and stored the webcam images of millions of internet users not suspected of wrongdoing. The surveillance program codenamed Optic Nerve collected still images of Yahoo webcam chats (one image every five minutes) in bulk and saved them to agency databases. The agency discovered "that a surprising number of people use webcam conversations to show intimate parts of their body to the other person", estimating that between 3% and 11% of the Yahoo webcam imagery harvested by GCHQ contains "undesirable nudity".[360]

March

[edit]The NSA has built an infrastructure which enables it to covertly hack into computers on a mass scale by using automated systems that reduce the level of human oversight in the process. The NSA relies on an automated system codenamed TURBINE which in essence enables the automated management and control of a large network of implants (a form of remotely transmitted malware on selected individual computer devices or in bulk on tens of thousands of devices). As quoted by The Intercept, TURBINE is designed to "allow the current implant network to scale to large size (millions of implants) by creating a system that does automated control implants by groups instead of individually."[361] The NSA has shared many of its files on the use of implants with its counterparts in the so-called Five Eyes surveillance alliance – the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia.

Among other things due to TURBINE and its control over the implants the NSA is capable of:

- breaking into targeted computers and to siphoning out data from foreign Internet and phone networks

- infecting a target's computer and exfiltrating files from a hard drive

- covertly recording audio from a computer's microphone and taking snapshots with its webcam

- launching cyberattacks by corrupting and disrupting file downloads or denying access to websites

- exfiltrating data from removable flash drives that connect to an infected computer

The TURBINE implants are linked to, and relies upon, a large network of clandestine surveillance "sensors" that the NSA has installed at locations across the world, including the agency's headquarters in Maryland and eavesdropping bases used by the agency in Misawa, Japan and Menwith Hill, England. Codenamed as TURMOIL, the sensors operate as a sort of high-tech surveillance dragnet, monitoring packets of data as they are sent across the Internet. When TURBINE implants exfiltrate data from infected computer systems, the TURMOIL sensors automatically identify the data and return it to the NSA for analysis. And when targets are communicating, the TURMOIL system can be used to send alerts or "tips" to TURBINE, enabling the initiation of a malware attack. To identify surveillance targets, the NSA uses a series of data "selectors" as they flow across Internet cables. These selectors can include email addresses, IP addresses, or the unique "cookies" containing a username or other identifying information that are sent to a user's computer by websites such as Google, Facebook, Hotmail, Yahoo, and Twitter, unique Google advertising cookies that track browsing habits, unique encryption key fingerprints that can be traced to a specific user, and computer IDs that are sent across the Internet when a Windows computer crashes or updates.[362][363][364][365]

The CIA was accused by U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee Chairwoman Dianne Feinstein of spying on a stand-alone computer network established for the committee in its investigation of allegations of CIA abuse in a George W. Bush-era detention and interrogation program.[366]

A voice interception program codenamed MYSTIC began in 2009. Along with RETRO, short for "retrospective retrieval" (RETRO is voice audio recording buffer that allows retrieval of captured content up to 30 days into the past), the MYSTIC program is capable of recording "100 percent" of a foreign country's telephone calls, enabling the NSA to rewind and review conversations up to 30 days and the relating metadata. With the capability to store up to 30 days of recorded conversations MYSTIC enables the NSA to pull an instant history of the person's movements, associates and plans.[367][368][369][370][371][372]

On March 21, Le Monde published slides from an internal presentation of the Communications Security Establishment Canada, which attributed a piece of malicious software to French intelligence. The CSEC presentation concluded that the list of malware victims matched French intelligence priorities and found French cultural reference in the malware's code, including the name Babar, a popular French children's character, and the developer name "Titi".[373]

The French telecommunications corporation Orange S.A. shares its call data with the French intelligence agency DGSE, which hands over the intercepted data to GCHQ.[374]

The NSA has spied on the Chinese technology company Huawei.[375][376][377] Huawei is a leading manufacturer of smartphones, tablets, mobile phone infrastructure, and WLAN routers and installs fiber optic cable. According to Der Spiegel this "kind of technology ... is decisive in the NSA's battle for data supremacy."[378] The NSA, in an operation named "Shotgiant", was able to access Huawei's email archive and the source code for Huawei's communications products.[378] The US government has had longstanding concerns that Huawei may not be independent of the People's Liberation Army and that the Chinese government might use equipment manufactured by Huawei to conduct cyberespionage or cyberwarfare. The goals of the NSA operation were to assess the relationship between Huawei and the PLA, to learn more the Chinese government's plans and to use information from Huawei to spy on Huawei's customers, including Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kenya, and Cuba. Former Chinese President Hu Jintao, the Chinese Trade Ministry, banks, as well as telecommunications companies were also targeted by the NSA.[375][378]

The Intercept published a document of an NSA employee discussing how to build a database of IP addresses, webmail, and Facebook accounts associated with system administrators so that the NSA can gain access to the networks and systems they administer.[379][380]