1981–1982 Iran Massacres

| Location | Iran |

|---|---|

| Type | Widespread executions |

| Target | Political and religious dissents, critics of Ruhollah Khomeini's government |

Between June 1981 and March 1982, the government of Iran carried out the largest political massacre in the country's history. This took place as part of the Iranian Cultural Revolution decreed by Ruhollah Khomeini on 14 June 1980, with the intent of "purifying" Iranian society of non-Islamic elements.[1][2] The killings and executions targeted thousands of political and religious dissidents, as well as critics, and is regarded a major crime against humanity.[3][4][5]

Historical Background

[edit]The massacre was carried out under the cover of the Iranian Cultural Revolution. Initiated by an order from Ayatollah Khomeini on June 14, 1980, the revolution aimed to "purify" higher education by removing Western, liberal, and leftist elements, leading to the closure of universities, the banning of student unions, and violent occupations of campuses. During this period, Shi’a clerics imposed policies to Islamize Iranian society, including mandatory hijabs for women, the expulsion of critical academics, the suppression of secular political groups, and the persecution of intellectuals and artists.[6][7][8][9]

These measures sparked large-scale protests across the country. On June 15, 1981, the National Front (Iran) and other secular opposition groups publicly criticized a proposal to Islamify the criminal justice system, prompting Ayatollah Khomeini to issue a fatwā, which led to the mass arrest of hundreds of protesters and critics.[1][10]

On June 20, 1981, a large anti-government protest took place in Iran, organized by the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran in response to the widely disputed impeachment of President Abolhassan Banisadr. Authorities announced that demonstrators, of any age, would be labeled as 'enemies of God' and executed. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps shot into crowds of protestors, resulting in around fifty deaths and over 200 injuries. The warden of Evin Prison later declared the execution of 23 protesters, including two teenage girls. Between June 22 and 27, the Chief Prosecutor announced the execution of an additional forty demonstrators, as well as ten left-wing activists.[1][11] Regime opponents retaliated with a bombing at the IRP headquarters.[12] This day marked the beginning of a wave of killings and executions led by the Islamic government.[13][14]

From June to November 1981, the Revolutionary Tribunals carried out the executions of 2,665 political prisoners. By August 1983, 5000 Iranian had been killed, and 12,500 by June 1985.[15] Most of those killed were young people.[16][17] This period in Iran became known as the "reign of terror".[18][19]

Targets

[edit]During this period the government carried out coordinated attacks against the civilian population through a state policy aimed at eliminating groups that were viewed as a threat. This included a wide range of Iranian citizens targeted due to their actual or suspected opposition to the Islamic Republic.[3][4]

According to official records the Iranian government labeled all its political opponents as "moharebs," "mufsids," counterrevolutionaries, "hypocrites," terrorists, "apostates," or pro-Western mercenaries. State-sponsored violence was not directed at a single group but aimed to eliminate a wide range of political ideologies that could challenge the state. These included liberals, nationalists, ethnic minorities, communists, Mujahedin-e Khalq (the largest opposition group), socialists, social democrats, monarchists, or followers of the Baháʼí Faith.[1]

Execution of minors and youth

[edit]During the massacre, hundreds of minors were also subjected to arbitrary detention, torture, and summary executions on ideologically motivated charges of ifsad-fi-alarz and moharebeh by the revolutionary courts.[20][1][21]

Between June 1981 and March 1982, the highest proportion of executions were of individuals aged 11 to 24. Most of these young activists were high school students or recent graduates from universities in Iran and abroad. Data also shows that over 10% of the victims were minors—under 18 years old. The youngest among them were Amrollah Kordi-Loo (1970-1981) and Elaheh Mohabbat (1965-1981), who were executed at 11 and 15 years old. In the context of Iran's modern social and historical situation, the execution of minors was an unprecedented and contentious event.[1][22]

Response from Iranian officials

[edit]

The ruling clerics intended to dismantle any prospects of blending modernism with Islam, a vision once idealistically pursued by President Banisadr. Even though Banisadr's father, Ayatollah Seyed Nasrollah Banisadr, had been "an Islamic leader revered by Khomeini", clerics saw him as a potentially dangerous Western, secular influence within the revolutionary government.[23]

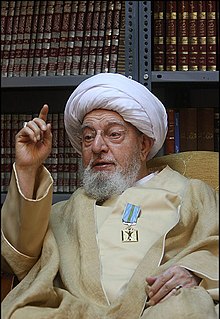

A three-man presidential council was formed in 1981. The council was headed by Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, with Akbar Rafsanjani and Mohammad-Ali Rajai as the other members. Mohammad Mohammadi Gilani was one of the judges that handed out death sentences to protestors. During a press conference, Gilani justified the trials and executions of the young girls, stating, "By the Islamic canon, a nine-year-old girl is mature. So there is no difference for us between a nine-year-old girl and a 40-year-old man."[24][25]

In a TV interview, Tehran Revolutionary Prosecutor Asadollah Lajevardi acknowledged that flogging and physical punishment were employed as effective strategies to promote "repentance" and to help integrate "political prisoners into the Islamic Republics order". This methodical use of torture aimed to alter prisoners' religious beliefs, political views, and worldviews, while also pressuring them to make false public confessions.[3]

Legal system

[edit]The 1981-1982 massacre marked a pivotal period when Sharia judges in Iran gained the power to define and enforce their interpretation of "Islamic justice". They used rulings and verdicts to turn terms such as "corruption on earth" and "waging war on Allah" into political tools, branding their critics as "hypocrites," "enemies of Allah," and "apostates." These terms were eventually codified in the 1982 Penal Code, which formed the basis of the modern Judicial system of the Islamic Republic of Iran.[26][1]

Those arrested were not allowed legal assistance, and confessions could be obtained under torture.[1] The large-scale execution of children breached Article 6(5) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Iran had ratified in 1975.[3]

Research

[edit]Research carried out by the Rastyad Collective documents over 3,500 executions in 85 different cities. The research includes the deaths of hundreds of minors, as well as burial sites. Speaking at an event organized by the University of Amsterdam and the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Javid Rahman, the UN Special Rapporteur on Iran, said that research on the 1981 Massacre was key to understanding the connections between the Iranian government's historical atrocities and its current human rights violations.[5][27]

See also

[edit]- Iranian revolution

- Aftermath of the Iranian revolution

- Timeline of the Iranian revolution

- Islamic fundamentalism in Iran

- Human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran

- International rankings of Iran

- Persecution of Baháʼís

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- Organizations of the Iranian revolution

External links

[edit]- Rastyad Collective "Short report about the 1981 massacre (English)" (YouTube video)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Nasiri, Shahin; Faghfouri Azar, Leila (28 July 2022). "Investigating the 1981 Massacre in Iran: On the Law-Constituting Force of Violence". Journal of Genocide Research. 26 (2): 164–187. doi:10.1080/14623528.2022.2105027. S2CID 251185903.

- ^ Bakhash (1984), pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b c d Rehman, Javaid. ""Atrocity Crimes" and grave violations of human rights committed by the Islamic Republic of Iran (1981–1982 and 1988)" (PDF).

- ^ a b "IRAN: FIVE YEARS OF FANATICISM". New York Times. 1984.

- ^ a b "Unveiling The Darkness: The 1981 Massacre In Post-Revolutionary Iran". Iranintl.

- ^ Khosrow Sobhe, “Education in Revolution: Is Iran Duplicating the Chinese Cultural Revolution?” Comparative Edu- cation 18, no. 3 (1982): 271-280.

- ^ Ruhollah Khomeini, Ṣaḥīfeh-ye Imām: An Anthology of Imam Khomeinī’s Speeches, Messages, Interviews, Decrees, Reli- gious Permissions, and Letters (vol. 12) (Tehran: The Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imām Khomeinī’s Works, 2008), 368-369.

- ^ Shahrzad Mojab, “State-University Power Struggle at Times of Revolution and War in Iran”, International Higher Edu- cation 36 (2004): 11-13; Nasser Mohajer, Voices of a Massacre: Untold Stories of Life and Death in Iran, 1988 (London: Oneworld, 2020), Appendix B.

- ^ Said Amir Arjomand, After Khomeini: Iran Under His Successors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 26.

- ^ Ruhollah Khomeini, Ṣaḥīfeh-ye Imām: An Anthology of Imam Khomeinī’s Speeches, Messages, Interviews, Decrees, Reli- gious Permissions and Letters (vol. 14) (Tehran: The Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imām Khomeinī’s Work, 2008), 392-393.

- ^ Abrahamian 1989, pp. 67, 68, 218, 219.

- ^ O'Hern, Steven K. (2012). Iran's Revolutionary Guard: The Threat that Grows While America Sleeps. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-823-1.

- ^ "Dream of Iranian revolution turns into a nightmare". csmonitor.

- ^ Nasiri, Shahin; Faghfouri Azar, Leila (2024). "Investigating the 1981 Massacre in Iran: On the Law-Constituting Force of Violence". Journal of Genocide Research. 26 (2): 164–187. doi:10.1080/14623528.2022.2105027.

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand (1999). Tortured Confessions. University of California Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-520-21866-6.

- ^ Child victims of exploitation : hearing before the Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families, House of Representatives, Ninety-ninth Congress, first session, hearing held in Washington, DC, on October 31, 1985. U.S. G.P.O. 1986.

- ^ Abrahamian 1989, pp. 68, 213, 233.

- ^ O'Hern, Steven K. (2012). Iran's Revolutionary Guard: The Threat that Grows While America Sleeps. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-823-1.

- ^ Kazemzadeh, Masoud (2023). TMass Protests in Iran: From Resistance to Overthrow. De Gruyter. p. 3.

- ^ Rastyad Collective. "Rastyad: online database concerning the 1981 Massacre in Iran". Rastyad.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Straaten, Floris van (19 June 2022). "Op zoek naar de verdwenen slachtoffers van de Iraanse revolutie". NRC (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Nadia Aghtaie and Jo Staines, “Child Execution in Iran: Furthering our Understanding of Child Execution as a Form of Structural Violence,” Critical Criminology (2022): 1-16.

- ^ "Iran: Terror in the Name of God". Time.com. 1981.

- ^ "Iran: Terror in the Name of God". Time.com.

- ^ "Dream of Iranian revolution turns into a nightmare". csmonitor.

- ^ Said Amir Arjomand, After Khomeini: Iran under his Successors. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 32; Reza Banakar and Keyvan Ziaee, “The Life of the Law in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” Iranian Studies 51, no. 5 (2018): 717-746.

- ^ "The 1981 Massacre in Iran: Uncovering a Forgotten Mass Atrocity". Tilburg University. 26 June 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abrahamian, Ervand (6 November 1989). Radical Islam: The Iranian Mojahedin. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850430773.

- Bakhash, Shaul (1984). Reign of the Ayatollahs. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-06888-X.

- Islamic courts and tribunals

- History of the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Massacres in Iran

- Executed people from Iran during the Islamic Republic

- 20th-century mass murder in Iran

- Police brutality in Iran

- Political repression in Iran

- Massacres committed by Iran

- Persecution of intellectuals

- Political imprisonment in Iran

- Extrajudicial killings in Iran

- Fatwas