Pressed Steel Car strike of 1909

| Pressed Steel Car strike of 1909 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Funeral procession in McKees Rocks for Bloody Sunday victims | |||

| Date | July 10 - September 8, 1909 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | wages | ||

| Methods | Strikes, Protest, Demonstrations | ||

| Resulted in | Wage increase; end to housing abuses | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Norton Hoffstot; | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

| Designated | October 14, 2000[1] | ||

The Pressed Steel Car strike of 1909, also known as the 1909 McKees Rocks strike, was an American labor strike which lasted from July 13 through September 8. The walkout drew national attention when it climaxed on Sunday August 22 in a bloody battle between strikers, private security agents, and the Pennsylvania State Police. At least 12 people died, and perhaps as many as 26.[2] The strike was the largest and most significant industrial labor dispute in the Pittsburgh area since the famous 1892 Homestead strike and was a precursor to the Great Steel Strike of 1919.

History of the strike

[edit]Background

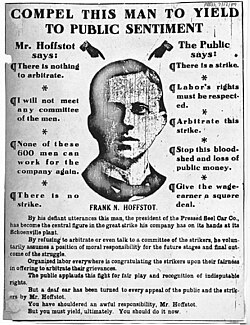

[edit]Frank Norton Hoffstot's Pressed Steel Car Company, sited downstream from Pittsburgh on the south bank of the Ohio River in McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, manufactured passenger and freight railroad cars on an assembly-line basis. It was America's second-largest rail car producer.[3] Pressed Steel employed a workforce of 6,000 people, mostly foreign born comprising 16 distinct ethnicities. The firm was infamous for its style of industrial peonage with immigrant workers.[4]

Working conditions in the plant were primitive even by Pittsburgh standards.[5] Pressed Steel Car Company was locally called "The Last Chance" and "The Slaughterhouse". In an interview with The Pittsburgh Leader, Rev. Father A.F. Toner, a priest at St. Mary Roman Catholic Church in McKees Rocks, said, "Men are persecuted, robbed, and slaughtered, and their wives are abused in a manner worse than death ... all to obtain or retain positions that barely keep starvation from the door." The local coroner, Joseph G. Armstrong, estimated that deaths in the plant averaged about one a day and were often caused by moving cranes. One of the charges made by Slavic immigrant workers was that their wives and daughters were subject to sexual harassment and preyed upon to deliver sexual favors as a way to repay food and rental debts, or forestall their collection, to the company agents.[6]

Particularly galling to the workers was the use of the Baldwin contract, commonly known as "pooling." Under this system, jobs were parceled out in lots by a foreman who contracted that it be done for a given sum, with the money paid to be divided pro rata by the men under him.[7] The system was rife with corruption, with workers often paying substantial kickbacks to the foreman to retain their jobs.[8] The system resulted in unpredictable and often insufficient rates of pay, as one sympathetic journalist reported:

President [Frank N.] Hoffstot says that it has proven to be a very satisfactory arrangement. And it has — for the company. As evidence of this we saw several pay envelopes showing that many of the workers slave for practically nothing. One envelope showed that the owner worked nine days, ten hours a day, and got $2.75; another eleven days and received $3.75; another three days and got $1.75; another four days and got $1, and the fifth, who had been idle for two months, worked three days and received nothing.... The company manages the pooling system through the foreman — and the workers are skinned until their bones shine. * * * Two years ago, before the pooling system was introduced, the men were making $3, $4, and $5 a day. Today most of them make 50 and 75 cents and $1 a day."[9]

Adding further to the destabilizing misery was the company-owned housing, ramshackle dwellings housing six families and renting for $12 a month.[8] Moreover, the company owned the stores from which the workers had to buy their provisions at inflated prices, lest they lose their jobs.[8] The system of economic domination was particularly severe and there came a day when the breaking point was reached.

The strike begins

[edit]

The strike was triggered on Saturday July 10, a payday on which many workers were shorter in their pay than usual. The men demanded an explanation; management refused to speak with the workers' representatives. James Rider, manager of The Pressed Steel Car Company, responded by hiring Pearl Bergoff, the notorious owner of strike-breaking paramilitary force.[10] The first fatality was an immigrant striker named Stephen Horvat, shot and killed by a black strikebreaker called Major Smith.[11] Two days later Berghoff had deployed 500 strikebreakers to the plant, most entering quietly by rail, although a boat called Steel Queen carrying 300 was rebuffed, at least initially, by strikers' gunfire on the shore.

The next day 200 state constables and 300 deputy sheriffs insured the safety of the strikebreakers and also began evicting strikers from company houses. The New York Times reported, "The illiterate foreigners were like so many savages today when they first caught sight of the khaki-clad constabulary who had come in during the night."[12]

The strikers were joined by members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), especially William Trautmann, one of its founders. Trautmann later published a novel, Riot, about the McKees Rocks strike. After Trautmann's arrest for strike organizing activities, Joe Ettor replaced him, and IWW leader Big Bill Haywood also arrived to rally strikers.[13]

In all, some 5,000 workers of the Pressed Steel Car Company's plant at McKees Rock went out on strike. These were joined by 3,000 others who worked for the Standard Steel Car Company of Butler and others in New Castle.[9]

An adjacent company-owned community, Presston (called Schoenville at the time and popularly referred to as "Hunky Town"), was at the heart of the strike. Presston workers were kept in constant debt to the company store and those behind in rent were evicted. On Saturday August 21 Deputy Sheriff Harry Exley assisted in one eviction by placing a baby buggy on top of a wagon laden with a Presston family's possessions. A photographer captured the moment. When it was printed in a Pittsburgh newspaper, the photo whipped up public sympathy for the strikers.

This set up the confrontation of the next day, August 22, "Bloody Sunday". A crowd of thousands of strikers who'd set up a checkpoint identified Exley, in civilian clothes, and targeted him for retaliation. In a fury the mob killed him, and clashed with Pennsylvania State Police mounted on horseback, called "Black Cossacks" by immigrant Slav workers.[14] One local source put the number of dead at sixteen, which includes Exley, two state troopers, and three strikers. Perhaps ten others were gravely hurt, "while scores were wounded by being shot in the legs, hit by bricks and clubbed into unconsciousness by the constabulary."[15] Martial law was declared the next day.

Settlement of the strike

[edit]The strike was settled on September 8 when Pressed Steel Car agreed to a wage increase, the posting of wage rates, and ending abuses in company housing practices.

Legacy

[edit]Before the strike was over,[16] and then in more detail in 1911, the strikebreakers appeared before federal panels to describe their own living and working conditions after they were brought to the conflict.[17] Held inside the plant or in boxcars against their will, fleeced, stolen from, physically threatened, and given rotten food, one hearing witness collapsed and was diagnosed with ptomaine poisoning.[16] Two hundred of the strikebreakers had responded by banding together in their own improvised union. They'd quit work and were camping on the nearby banks of the Ohio River in an attempt to collect back wages, naming Chief of Police Farrell of the Coal and Iron Police and Pearl Bergoff's lieutenant Sam Cohen as those most responsible. Lawyer for the strikebreakers was the ambitious William N. McNair, who alleged that this treatment amounted to peonage. McNair would later serve one chaotic term as Mayor of Pittsburgh in 1934.

On August 22, 2009 the Pennsylvania Labor History Society and the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission dedicated a state historical marker there to commemorate the strike's centennial.[18]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search" (Searchable database). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ Marylynne Pitz, "Pressed Steel Car strike in McKees Rocks reaches centennial anniversary". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 16, 2009, pg. E1.

- ^ Edward Levinson, I Break Strikes: The Technique of Pearl L. Bergoff. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1935; pg. 71.

- ^ Charles McCollester, The Point of Pittsburgh: Production and Struggle at the Forks of the Ohio. Pittsburgh: Battle of Homestead Foundation, 2008; pg. 181.

- ^ Crystal Eastman, Work-Accidents and the Law. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications, 1910.

- ^ McCollester, The Point of Pittsburgh, pg. 182.

- ^ Louis Duchez, "The Strikes in Pennsylvania," The International Socialist Review, vol. 10, no. 3 (September 1909), pg. 194.

- ^ a b c Duchez, "The Strikes in Pennsylvania," pg. 195.

- ^ a b Duchez, The Strikes in Pennsylvania, pp. 194-195.

- ^ Levinson, I Break Strikes, p. 70.

- ^ "Sheriff Refuses to Evict Strikers" (PDF). New York Times. 12 August 1909. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Levinson, I Break Strikes, pg. 77.

- ^ Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 4: Industrial Workers of the World. New York: International Publishers, 1965; pg. 235.

- ^ McCollester, The Point of Pittsburgh, pg. 184.

- ^ "More Troops Desired at Schoenville". New Castle (PA) Times. 23 August 1909. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Tell Stories of Brutality - Strikebreakers Complain of Bad Treatment at Schoenville". Evening Review, East Liverpool, Ohio. 28 August 1909. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Peonage in Western Pennsylvania: Hearings Before the Committee on Labor of the House of Representatives, Sixty-second Congress, First Session, on House Resolution, Issue 90. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1911. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Pitz, Marylynne (August 16, 2009). "Historical marker commemorates Presston". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

External links

[edit]- Pressed Steel Car strike in McKees Rocks reaches centennial anniversary

- "1909 McKees Rocks Strike Historical Marker". Explore PA History. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Pennsylvania Labor History Society

- United Steelworkers

- 1909 labor disputes and strikes

- 1909 in Pennsylvania

- Labor disputes led by the Industrial Workers of the World

- Labor disputes in Pittsburgh

- Protest-related deaths

- Manufacturing industry labor disputes in the United States

- July 1909 events

- August 1909 events

- September 1909 events

- 1900s strikes in the United States

- 1900s in Pittsburgh