BPM (Beats per Minute)

| BPM (Beats per Minute) | |

|---|---|

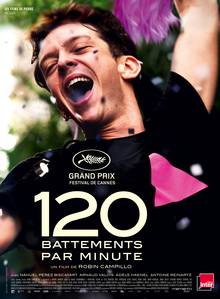

Theatrical release poster | |

| French | 120 battements par minute |

| Directed by | Robin Campillo |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jeanne Lapoirie |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Arnaud Rebotini |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Memento Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 140 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | $5.8 million[1] |

| Box office | $7.7 million[2] |

BPM (Beats per Minute), also known as 120 BPM (Beats per Minute),[a] (French: 120 battements par minute) is a 2017 French drama film directed by Robin Campillo and starring Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, Arnaud Valois and Adèle Haenel. The film is about the AIDS activism of ACT UP Paris in 1990s France. Campillo and co-screenwriter Philippe Mangeot drew on their personal experiences with ACT UP in developing the story.

It had its world premiere at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, followed by screenings at other festivals. At Cannes it won critical acclaim and four awards, including the Grand Prix. It went on to win six César Awards, including Best Film, and other honours.

Plot

[edit]In the early 1990s, a group of HIV/AIDS activists associated with the Paris chapter of ACT UP struggle to effect action to fight the AIDS epidemic. While the French government has declared its intent to support HIV/AIDS sufferers, ACT UP stages public protests against their sluggish pace, accusing the government of censoring and minimizing the fight against the virus. When the pharmaceutical company Melton Pharm announces its plans to reveal its HIV trial results at a prominent pharmaceutical conference the following year, ACT UP invades its offices with fake blood and demands it release its trial results immediately. While ACT UP makes some headway with its public protests, its members fiercely debate the group's strategy, with conflicting goals of showmanship and persuasion, with conflicting aesthetics of positivity and misery. ACT UP struggles to plan a more effective Gay Pride parade than in previous years, bemoaning the depressing, "zombie" atmosphere the AIDS epidemic had created.

The film shows a number of large meetings in a lecture theatre where the radical element demand more direct action and others aim to bring the scientists to meetings where they can get them to communicate results sooner. A deaf person points out they can do direct action AND pursue meetings with the labs. But soon some radicals have attacked Helene, the mother of a teenager who contracted HIV through blood transfusion. Helene had pushed for politicians to be tried and jailed for their mishandling of blood screening (which is how her son got HIV). To some this is against ACT-UP principles as prison is an unsafe place where people get HIV. The group always seem to be arguing.

The film gradually shifts from the political storyline of ACT UP's actions to the personal stories of ACT UP members. Foreshadowing later events in the movie, Jeremie, a youth who lives with HIV in the group sees his health deteriorate rapidly. Per his wishes, the group parades in the streets after his death, putting his name and face to the ranks of AIDS victims. Newcomer Nathan, a gay man who doesn't live with HIV, begins to fall in love with the passionate veteran Sean, who is HIV-positive. Nathan and Sean start a sexual relationship, and discuss their sexual histories. Sean got HIV when he was sixteen from his married maths teacher. Sean is already exhibiting signs of the disease's progression and soon his T-cell count is down to 160. Nathan offers to care for Sean as he gets worse. When Sean is released from hospital to Nathan's apartment for end-of-life care, Nathan euthanizes him. ACT UP holds a wake at their home. As per Sean's wishes, later they invade a health insurance conference, throwing his ashes over the conference-goers and their food.

Cast

[edit]- Nahuel Pérez Biscayart as Sean Dalmazo

- Arnaud Valois as Nathan

- Adèle Haenel as Sophie

- Antoine Reinartz as Thibault

- Félix Maritaud as Max

- Médhi Touré as Germain

- Aloïse Sauvage as Eva

- Simon Bourgade as Luc

- Catherine Vinatier as Hélène

- Saadia Ben Taieb as Sean's Mother

- Ariel Borenstein as Jérémie

- Théophile Ray as Marco

- Simon Guélat as Markus

- Jean-François Auguste as Fabien

- Coralie Russier as Muriel

- Samuel Churin as Gilberti (Melton Pharm)

- François Rabette as Michel Bernin

Production

[edit]Director Robin Campillo co-wrote the screenplay, describing himself as "an ACT UP militant in the '90s",[6] meaning he did not have to carry out any other investigation into how to accurately portray the experience. One scene was also based on his experience with the AIDS epidemic, as he said "I've dressed up a boyfriend on his death".[6] Co-screenwriter Philippe Mangeot was also involved in ACT UP.[7]

At Cannes, Campillo explained his decision to go ahead with directing the film, saying "BPM is above all a film I wanted to make where the force of words transforms into pure moments of action".[8] The budget of $5 million was raised in months.[6]

The film was shot in Paris and partly in Orléans, including at the former La Source hospital.[9][10]

Release

[edit]

The film had its world premiere at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival on 20 May 2017.[11] On 24 June, it went to the Moscow International Film Festival,[12] followed by the New Zealand International Film Festival in July.[13] With the number of films at the Toronto International Film Festival being reduced from 2016, BPM (Beats per Minute) was nevertheless selected for the 2017 festival in September.[14]

At Cannes, The Orchard acquired U.S. distribution rights to the film.[15] It has been released in France on 23 August 2017 as scheduled.[16]

Incidents

[edit]On 4 February 2018, a group of Christian protesters holding icons and singing church chants disrupted the screening of BPM at the Romanian Peasant Museum in Bucharest. Displaying banners with nationalist and Christian messages,[17] the protesters claimed that "a film with this plot is inadmissible to be screened" at the Romanian Peasant Museum, because "it is a film about homosexuals", and "the Romanian peasant is Orthodox Christian."[18] After half an hour of dispute, the police took the protesters out of the cinema.[19] The screening of BPM was part of a series of events dedicated to LGBT History Month. Director Tudor Giurgiu, a supporter of LGBT rights and witness to what happened, criticized in a Facebook post such demonstrations and asked for protection measures in cinema halls where LGBT-themed films are screened.[20]

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]On the French review aggregator AlloCiné, the film has an average review score of 4.5 out of 5 based on 31 critics,[21] making it the highest rated film of the year.[22] It holds a 99% approval rating on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 138 reviews, with a weighted average of 8/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Moving without resorting to melodrama, BPM offers an engrossing look at a pivotal period in history that lingers long after the closing credits roll."[23] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 84 out of 100, based on 25 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[24]

Jada Yuan, writing for Vulture.com, spoke of being moved to tears by the film, praising it as "a unique, intimate portrait of the community from the inside".[25] The Toronto Star's Peter Howell observed French critics at Cannes were generally excited about it and opined it deserved a top award.[26] The Hollywood Reporter critic David Rooney positively reviewed the dialogue and the youthful cast, while criticizing the pace.[27] Tim Robey, writing for The Daily Telegraph, gave it three of five stars, complimenting the comedic moments and a sex scene, balancing awareness of risk, with one character being HIV positive, and sexiness.[28] Vanity Fair critic Richard Lawson hailed it as a "half sober and surveying docudrama, half wrenching personal illness narrative".[29] Lawson and The Hollywood Reporter critics compared the film to the play The Normal Heart by Larry Kramer.[6][27][29]

Accolades

[edit]It competed for the Palme d'Or in the main competition section at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival.[30][31] In July 2017, it was listed among 10 films in competition for the Lux Prize.[32] It was selected as the French entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 90th Academy Awards, but it was not nominated.[33]

See also

[edit]- List of submissions to the 90th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of French submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "120 battements par minute (Beats Per Minute) (2017)". JP's Box-Office. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "BPM (Beats Per Minute) (2017) - International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Lawson, Richard (20 May 2017). "120 Beats Per Minute Cannes Review". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Salmon, Caspar (5 April 2018). "120 Beats per Minute (BPM) review: queer lives honoured". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "120 BPM (Beats Per Minute)". Curzon Artificial Eye. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Kilday, Gregg (20 May 2017). "Cannes: '120 Beats Per Minute' Director Says 'I Was an ACT UP Militant'". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Regnier, Isabelle (20 May 2017). "Cannes 2017 : avec « 120 battements par minute », les corps en lutte d'Act Up conquièrent les cœurs". Le Monde. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Gilchrist, Tracy E. (28 May 2017). "AIDS Activism Movie 120 Beats Per Minute Honored with Prestigious Award at Cannes". The Advocate. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Lemercier, Fabien (20 July 2016). "Shooting set to begin for BPM (Beats per Minute)". Cineuropa. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "L'ancien hôpital de La Source accueille le tournage du film 120 battements par minute". La République du Centre. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "2017 Screenings Guide" (PDF). Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "120 BEATS PER MINUTE". Moscow International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Gibson, Nevil (27 June 2017). "Cannes trifecta of winners take top slots at NZ International Film Festival". National Business Review. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Howell, Peter (25 July 2017). "TIFF announces first batch of this year's movies — including two Matt Damon films". The Toronto Star. Toronto Star Newspapers. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (23 May 2017). "The Orchard Lands Cannes Competition Pic 'BPM'; Samuel Goldwyn Inhales Tribeca's 'Holy Air'". Deadline Hollywood. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "120 Battements par Minute". Memento Films. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Cristescu, George-Andrei (4 February 2018). "Proiecția unui film cu tematică gay, premiat la Festivalul de la Cannes, întreruptă în această seară de un grup de credincioși, la Muzeul Țăranului Român". Adevărul (in Romanian). Adevarul Holding.

- ^ Cioroianu, Alexandra-Maria (5 February 2018). "SCANDAL la Muzeul Țăranului Român - Proiecția unui film, întreruptă de credincioși: 'Hey Soros, leave them kids alone...' / VIDEO". Știri pe surse (in Romanian).

- ^ Macovei, Ștefana (5 February 2018). "Scandal la Muzeul Țăranului Român. Proiecția filmului 120 de Bătăi pe Minut a fost întreruptă de un grup religios". Elle Romania (in Romanian). Ringier Romania.

- ^ "VIDEO/Scandal la MȚR. Un film cu tematică gay, întrerupt de un grup de credincioși. Tudor Giurgiu: "E ireal, rușine!"". Libertatea (in Romanian). Ringier Romania. 4 February 2018.

- ^ "120 battements par minute". AlloCiné. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "Les meilleurs films selon la presse". AlloCiné. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "120 Beats Per Minute (2017)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "120 Beats Per Minute Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Yuan, Jada (26 May 2017). "The French AIDS-Crisis Film That Had Journalists Weeping at Cannes". Vulture. New York Media. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Howell, Peter (26 May 2017). "And the Palme d'Or at Cannes goes to — who knows?: Howell". The Toronto Star. Toronto Star Newspapers. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Rooney, David (20 May 2017). "'120 Beats Per Minute' ('120 Battements par minute'): Film Review, Cannes 2017". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Robey, Tim (26 May 2017). "Cannes 2017, 120 Beats Per Minute review: a vitally erotic, moving ode to activism". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Lawson, Richard (20 May 2017). "AIDS Drama 120 Beats Per Minute Is a Vital New Gay Classic". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "The 2017 Official Selection". Cannes Film Festival. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ Winfrey, Graham (13 April 2017). "2017 Cannes Film Festival Announces Lineup: Todd Haynes, Sofia Coppola, 'Twin Peaks' and More". IndieWire. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Official Selection". Lux Prize. European Parliament. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Richford, Rhonda (19 September 2017). "Oscars: France Selects '120 Beats Per Minute' for Foreign-Language Category". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Le Palmarès des Swann d'Or 2017". Cabourg Film Festival. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (28 May 2017). "2017 Cannes Film Festival Award Winners Announced". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Hopewell, John (27 May 2017). "Cannes Critics Prize 'BPM,' Closeness,' 'Nothing Factory'". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Naselli, Adrian (4 May 2017). "EXCLUSIVITÉ TÊTU : Tous les films en compétition de la Queer Palm au Festival de Cannes". Têtu. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ wyzman (27 May 2017). "Cannes 2017 : 120 battements par minute décroche la Queer Palm" [Cannes 2017: 120 Beats per Minute wins the Queer Palm]. Ecran Noir (in French). Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Richford, Rhonda (31 January 2018). "'120 BPM' Leads France's Cesar Awards Nominations". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Parant, Paul; Balle, Catherine (2 March 2018). "DIRECT. César 2018 : Camélia Jordana et Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, meilleurs espoirs". Le Parisien. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Fagerholm, Matt (23 October 2017). ""Killing Jesús" Wins the Roger Ebert Award at the 2017 Chicago International Film Festival". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Cabeza, Elisabet (4 November 2017). "'The Square' leads 2017 European Film Awards nominations". Screen Daily. Screen International. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (14 November 2017). "Andrey Zvyagintsev's 'Loveless' Wins Two European Film Awards". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ La Rédaction (13 February 2018). "PHOTOS Globes de cristal: Doria Tillier sexy, Camile Cerf et Audrey Dana élégantes". Voici. Prisma Média. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ Haimi, Rebecca (4 January 2018). "Flest nomineringar till Borg – Östlund: "Det känns okej"". SVT (in Swedish). Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ Pettersson, Leo (22 January 2018). "Glädjetårar efter Sameblods succé". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ FP Staff (28 November 2017). "IFFI 2017 complete winners list: Parvathy wins Best Actress; Amitabh Bachchan is 'Film Personality of The Year'". Showsha. Firstpost. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Lewis, Hilary (21 November 2017). "Independent Spirit Awards: 'Call Me by Your Name' Leads With 6 Nominations". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (3 December 2017). "Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. Crowns 'Call Me by Your Name' Best Picture of 2017". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Richford, Rhonda (5 February 2018). "'120 BPM' Tops France's Lumiere Awards". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ TANJUG (14 December 2017). "'"120 otkucaja u minuti" najbolji film na Merlinka festivalu". B92 (in Serbian). Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (6 January 2018). "'Lady Bird' Named Best Film of 2017 by National Society of Film Critics". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "'Lady Bird' Named Best Picture by New York Film Critics Circle". Variety. Penske Business Media. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ Staff (28 December 2017). "Get Out Wins Big at Online Film Critics Society Awards". Den of Geek. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Nieszawer, Céline (29 September 2017). "'120 BEATS PER MINUTE' by Robin Campillo, 18th Sebastiane Award". Premios Sebastiane (in European Spanish). Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Pond, Steve (29 November 2017). "'Dunkirk,' 'The Shape of Water' Lead Satellite Award Nominations". TheWrap. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (18 December 2017). "'Lady Bird' Named Best Film of 2017 by Vancouver Critics Circle". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ The Washington, D.C. Area Film Critics Association (8 December 2017). "'Get Out' Is In with D.C. Film Critic". PR Newswire. Cision. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

External links

[edit]- 2017 films

- 2017 drama films

- 2017 LGBTQ-related films

- 2010s French-language films

- Films about activists

- Films directed by Robin Campillo

- Films produced by Marie-Ange Luciani

- Films with screenplays by Robin Campillo

- Films set in the 1990s

- Films set in Paris

- Films shot in Paris

- Films shot in Loiret

- French political drama films

- French LGBTQ-related films

- Best Film César Award winners

- Gay-related films

- HIV/AIDS in French films

- LGBTQ-related political drama films

- The Orchard (company) films

- Queer Palm winners

- Cannes Grand Prix winners

- 2010s French films

- Films featuring a Best Actor Lumières Award–winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor César Award–winning performance

- Films whose director won the Best Director Lumières Award

- Best Film Lumières Award winners

- Films scored by Arnaud Rebotini