Columbia University Libraries

| Columbia University Libraries | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | New York City, U.S. |

| Type | Academic library system |

| Established | 1756 |

| Branches | 19 |

| Collection | |

| Size | 15.0 million[1] |

| Access and use | |

| Circulation | 252,577 (2016) |

| Population served | over 4 million |

| Other information | |

| Budget | US$70 million[1] |

| Director | Ann D. Thornton |

| Employees | 501 (2020) |

| Website | library |

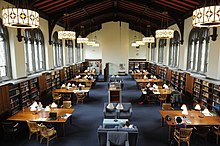

Columbia University Libraries is the library system of Columbia University and one of the largest academic library systems in North America. With 15.0 million volumes and over 160,000 journals and serials, as well as extensive electronic resources, manuscripts, rare books, microforms, maps, and graphic and audio-visual materials, it is the fifth-largest academic library in the United States and the largest academic library in the State of New York. Additionally, the closely affiliated Jewish Theological Seminary Library holds over 400,000 volumes, which combined makes the Columbia University Libraries the third-largest academic library, and the second-largest private library in the United States.[2]

The services and collections are organized into 19 libraries and various academic technology centers, including affiliates. The organization is located on the university's Morningside Heights campus in New York City and employs more than 500 professional and support staff. Additionally, Columbia Libraries is part of the Research Collections and Preservation Consortium (ReCAP) along with the Harvard Library, Princeton University Library, and New York Public Library.

History

[edit]

The Columbia University Libraries began with the 1756 donation of the estate and library of Joseph Murray to the university, then known as King's College.[3]: 428 Valued at around £8,000, it was the largest single philanthropic gift made in colonial America.[4] In 1763 the college received over 1,000 volumes from Reverend Duncombe Bristowe of London, through the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts.[5]: 428 Among its early gifts, the college recorded that "Sundry gentlemen at Oxford gave books, whose names are in them", and in 1772 the college received directly from Oxford University, at the request of President Myles Cooper, a copy of every book published by the Oxford University Press.[6]

The King's College collection would largely not survive the American Revolutionary War. In 1776, College Hall was commandeered by the New York Committee of Safety to be used as a military hospital and instruction was suspended,[7]: 49 in preparation for which the contents of the college's library had been deposited in the New York City Hall.[5]: 430 Only six or seven hundred items from the King's College library were recovered following the war, and only 111 remain in Columbia University's collections today.[5]: 430 Following the war, the newly renamed Columbia College's library was rebuilt and grew over time through gifts, deposits, and purchases; by 1863 it owned nearly 15,000 volumes.[5]: 438 Valuable acquisitions during this time period included the 1825 purchase of 264 books from the library of Lorenzo Da Ponte, and the donation of the library of Nathaniel Fish Moore to the college.[8][5]: 435

The physical location of the library has moved several times over the course of the university's history. Originally housed in College Hall on Columbia's Park Place campus, it relocated to the university's newly acquired Madison Avenue campus in 1857. A new building for the library designed by Charles C. Haight was completed in 1883.[5]: 439 From 1883 to 1888, Melvil Dewey, the creator of the Dewey Decimal Classification and a founder of the American Library Association, was the chief librarian at Columbia, where he also founded the world's first library school in 1887.[9] As librarian, Dewey reorganized the Columbia Libraries, unifying them under one efficient administration and creating a staff service.[5]: 439

In the 1890s Columbia was declared a university and moved to its current location in Morningside Heights. There, the Low Memorial Library was built in 1895 to serve as the centerpiece of the new campus. Financed with $1 million of University President Seth Low's own money, at full capacity the library was expected to house 1.9 million volumes.[10] However, the library at this point was growing quickly, and the Low Library would soon not be enough to accommodate its entire collection: in 1904 the Columbia University Libraries held around 400,000 books, a number which would swell to more than a million in little over two decades.[11] Butler Library, currently Columbia's main library, was built 1931 in and funded by a $4 million gift from alumnus and philanthropist Edward Harkness.[3]: 196–197 Following its opening in 1934, only special collections, Columbiana, and the East Asian, mathematics, and general sciences sections remained in Low; those too would eventually be relocated elsewhere.[11]

In 1974 the library became, along with Harvard Library, Yale Library, and New York Public Library, a founding member of the Research Libraries Group.[11]

Collection

[edit]As of 2020, the Columbia library system contains over 15.0 million volumes, its collections including over 160,000 journals and serials, six million microfilms, 26 million manuscripts, over 600,000 rare books, over 100,000 videos and DVDs, and nearly 200,000 government documents. The library's collection would stretch 174 miles end-to-end, and is growing at a pace of 140,000 items per annum. The system attracts over four million visitors a year.[12]

The Columbia Center for Oral History Research, the oldest academic oral history research program, was founded at Columbia by Professor Allan Nevins in 1948.[13] Its oral history archives are stored in Butler Library, and contain over 12,000 interviews.[14]

Columbia shares an off-site shelving facility, located in Plainsboro, New Jersey, with the Research Collections and Preservation Consortium (RECAP), which includes the New York Public Library and the library systems of Harvard University and Princeton University.[15][16] The system is participating in the Google Books Library Project.[17]

Libraries at Columbia

[edit]

The libraries in the Columbia system include:[18]

- Arthur W. Diamond Law Library

- Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library

- Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library

- Barnard College Library (affiliate)

- Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary

- Butler Library

- C.V. Starr East Asian Library

- Gabe M. Weiner Music & Arts Library

- Gottesman Libraries (affiliate)

- Jewish Theological Seminary Library (affiliate)

- Journalism Library

- Lehman Social Sciences Library

- Mathematics Library

- Milstein Undergraduate Library

- Rare Book & Manuscript Library

- S. Steven Pan '88 Business Library

- Science & Engineering Library

- Social Work Library

- Thomas J. Watson Library of Business & Economics

Librarians

[edit]

The first recorded librarian of the Columbia Libraries was Robert Harpur, a professor of mathematics at King's College who was appointed in 1763 to "make a catalogue of the Books that now are and hereafter may belong to the Library... and also that he be accountable for the said Books."[20]: 429 Following the Revolutionary War, during which the library was largely destroyed, the role of librarian would fall on college professors in rotation: in 1799 the board of trustees "Resolved that the care of the Library be committed to the Professor of Languages and the Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy."[20]: 432

In order to slow the hemorrhaging of books from the library's collections, it was restructured in 1817 and 1821, when it was placed under the control of the college's president and then board of trustees, respectively. Beginning in 1817, the youngest professor of the college would serve as the librarian, including physicist and engineer James Renwick, astronomer and geologist Henry James Anderson, and adjunct professor of classics Robert George Vermilye.[20]: 434 The first full-time librarian appointed by Columbia was classics professor Nathaniel Fish Moore in 1837; he would go on to serve as the college's president following his tenure.

| Name | Tenure | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Harpur | 1763–1767 | [20] | |

| James Renwick | 1821–1825 | served ex-officio as youngest professor (natural philosophy) | [20] |

| Henry James Anderson | 1825–1835 | served ex-officio as youngest professor (mathematics and astronomy) | [20] |

| Robert George Vermilye | 1835–1837 | served ex-officio as youngest professor (classics) | [20] |

| Nathaniel Fish Moore | 1837–1839 | [20] | |

| George C. Schaeffer | 1839–1847 | [20] | |

| Lefroy Ravenhill | 1847–1851 | [20] | |

| William Alfred Jones | 1851–1865 | [20] | |

| Beverly Robinson Betts | 1865–1883 | [20] | |

| Melvil Dewey | 1883–1889 | [21] | |

| George Hall Baker | 1889–1889 | [21] | |

| James Hulme Canfield | 1889–1909 | [21] | |

| William Dawson Johnston | 1909–1913 | [21] | |

| Frederick Hicks | 1914–1914 | [21] | |

| Dean Putnam Lockwood | 1915–1916 | acting librarian; professor of philology | [21] |

| William Henry Carpenter | 1917–1925 | acting librarian; provost | [21] |

| Roger Howson | 1926–1940 | as "University Librarian" | [21] |

| Charles C. Williamson | 1926–1943 | as "Director of Libraries" and dean of the Columbia School of Library Service | [21] |

| Carl M. White | 1943–1953 | [21] | |

| Richard Logsdon | 1953–1969 | [21] | |

| Donald C. Anthony | 1969–1969 | acting librarian | [21] |

| Warren J. Haas | 1969–1978 | [11] | |

| Patricia Battin | 1978–1987 | [11] | |

| Elaine P. Sloan | 1988–2001 | [11] | |

| James G. Neal | 2001–2014 | [11] | |

| Ann Thornton | 2015– | [11] |

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mian, Anam; Roebuck, Gary (2020). ARL Statistics 2020. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

- ^ "About The Library". www.jtsa.edu. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ^ a b Columbia University (1904). A History of Columbia University, 1754–1904. Columbia University Press, The Macmillan Company, agents.

- ^ Foner, Eric (2016). "Eric Foner's Report". columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-01-24. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Columbia University (1904). A History of Columbia University, 1754–1904. Columbia University Press, The Macmillan Company, agents.

- ^ Bonnell, Alice H. (May 1976). "'Sundry Gentlemen at Oxford'" (PDF). Columbia Library Columns. 15 (3): 16–25.

- ^ McCaughey, Robert A. (2003). Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University in the City of New York, 1754-2004. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13008-0.

- ^ Hond, Paul (Winter 2020–2021). "How Mozart's Librettist Became the Father of Italian Studies at Columbia". Columbia Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-01-08. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ^ "About Melvil Dewey, 1851–1931 (The Dewey Program at the Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-07-26. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- ^ "Low Memorial Library, Columbia University, New York (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "History of Collections | Columbia University Libraries". library.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

- ^ "Fast Facts about Columbia University Libraries". columbia.edu.

- ^ "Oral History, Policy History, and Information Abundance and Scarcity | Perspectives on History | AHA". www.historians.org. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ "Oral History Archives at Columbia | Columbia University Libraries". library.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ "About ReCAP". recap.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ "Debate at N.Y. Public Library: Can Off-Site Storage Work for Researchers?" Jennifer Howard. April 22, 2012. Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ "Library Partners". google.com.

- ^ Neal, James (2014). "Guide to the Libraries, 2013-2014" (PDF). Columbia University Libraries. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-03.

- ^ "Card, Discard". Columbia Magazine. Retrieved 2021-12-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l University, Columbia (1904). A History of Columbia University, 1754–1904. Columbia University Press, The Macmillan Company, agents.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kent, Allen; Lancour, Harold (1971-07-01). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science: Volume 5 - Circulation to Coordinate Indexing. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8247-2005-6.