University of Dundee

Official Coat of Arms (as granted by Lyon Court) | |

| Latin: Universitas Dundensis | |

| Motto | Latin: Magnificat anima mea dominum[1] |

|---|---|

Motto in English | "My soul doth magnify the Lord" |

| Type | Public university |

| Established | 1967 – gained independent university status by royal charter 1897 – Constituent college of the University of St Andrews 1881 – University College |

| Endowment | £34.4 million (2023)[2] |

| Budget | £325.3 million (2022/23)[2] |

| Chancellor | The Baron Robertson of Port Ellen |

| Rector | Keith Harris |

| Principal | Iain Gillespie[3] |

Academic staff | 1,440 (2022/23)[4] |

Administrative staff | 1,770 (2022/23)[4] |

| Students | 17,365 (2022/23)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 11,145 (2022/23)[5] |

| Postgraduates | 6,220 (2022/23)[5] |

| Location | , Scotland, UK |

| Colours | |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | dundee |

| |

The University of Dundee[a] is a public research university based in Dundee, Scotland. It was founded as a university college in 1881 with a donation from the prominent Baxter family of textile manufacturers. The institution was, for most of its early existence, a constituent college of the University of St Andrews alongside United College and St Mary's College located in the town of St Andrews itself. Following significant expansion, the University of Dundee gained independent university status by royal charter in 1967 while retaining elements of its ancient heritage and governance structure.

The main campus of the university is located in Dundee's West End, which contains many of the university's teaching and research facilities; the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, Dundee Law School and the Dundee Dental Hospital and School. The university has additional facilities at Ninewells Hospital, containing its School of Medicine; Perth Royal Infirmary, which houses a clinical research centre; and in Kirkcaldy, Fife, containing part of its School of Health Sciences. The annual income of the institution for 2022–23 was £325.3 million of which £78.9 million was from research grants and contracts, with an expenditure of £320.8 million.[2]

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

The University of Dundee has its roots in the earlier university college based in Dundee and the University of St Andrews. During the 19th century, the growing population of Dundee significantly increased demand for the establishment of an institution of higher education in the city and several organisations were established to promote this end, including a University Club in the city. There was a significant movement with the intention of moving the entire university to Dundee (which the royal commission[which?] observed was now a "large and increasing town") or the establishment of a college along very similar lines to the present United College. Finally, agreement was reached that what was needed was expansion of the sciences and professions, rather than the arts at St Andrews.[6]

A donation of £120,000 for the creation of an institution of higher education in Dundee was made by Miss Mary Ann Baxter of Balgavies, a notable lady of the city and heir to the fortune of William Baxter of Balgavies. In this endeavour, she was assisted by her relative, John Boyd Baxter, an alumnus of St Andrews and Procurator Fiscal of Forfarshire who also contributed nearly £20,000. In order to craft the institution and its principles, it was to be established first as an independent university college, with a view from its very inception towards incorporation into the University of St Andrews.[6]

In 1881, the ideals of the proposed new college were laid down, suggesting the establishment of an institute for "promoting the education of persons of both sexes and the study of Science, Literature and the Fine Arts". The university currently identifies 1881 as the year of its foundation, as University College's endowment was dated 31 December 1881, but the year 1880, when the announcement of Mary Ann Baxter's funding was made, as well as the years 1882 and 1883 have also been cited as their foundation year by the institution in the past.[7]

No religious oaths were to be required of members. Later that year, "University College, Dundee" was established as an academic institution and the first principal, Sir William Peterson, was elected in late 1882. When opened in 1883, it comprised five faculties: Maths and Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, Engineering and Drawing, English Language and Literature and Modern History, and Philosophy. The University College had no power to award degrees and for some years some students were prepared for external examinations of the University of London.[8] By 1894, the faculties offered at the college remained essentially scientific in outlook, with three academics - including the principal, William Peterson - giving instruction in classics, philosophy, English and history at both the Dundee and St Andrews sites.[9]

The policy of no discrimination between the sexes, which was insisted upon by Mary Ann Baxter, meant that the new college recruited several able female students. Their number included the social reformer Mary Lily Walker and, later, Margaret Fairlie who in 1940 became Scotland's first female professor.[10][11] Another early female graduate, Ruth Wilson, later Young, became professor of surgery at Lady Hardinge Medical College in Delhi and later became its principal.[12]

Incorporation into the University of St Andrews

[edit]

Following discussions around various forms of incorporation and association, students were able to matriculate through the University of St Andrews from 1885.[13] The full incorporation was completed in 1897 when University College became part of the University of St Andrews. This move was of notable benefit to both, enabling the University of St Andrews (which was in a small town) to support a medical school. Medical students could choose to undertake preclinical studies either in Dundee or St Andrews (at the Bute Medical School) after which all students would undertake their clinical studies at Dundee. Eventually, law, dentistry and other professional subjects were taught at University College. By 1904 University College had a roll of 208, making up 40 per cent of the roll of the university generally. By session 1909-10 234 students were studying at University College, 101 of whom were female. Among the notable students at this time were Robert Watson-Watt, the radar pioneer; William Alexander Young the epidemiologist who later died in Accra while studying yellow fever; and David Rutherford Dow who would go on to be a senior member of staff at the college.[14]

In 1895, unlike the students at St Andrews, there were reportedly very few "bona-fide" matriculated students at Dundee who were "aiming to graduate".[15] During the academic years of 1892–4, those students at Dundee who had matriculated at St Andrews were considered St Andrews University students and were subsequently awarded degrees by St. Andrews. Although the union between the two institutions was then threatened by a lawsuit, by 1898 the union with St. Andrews was restored on the original basis.[16][17]

University College's development in the early twentieth century has been described as "slow and fitful" and the interwar period saw virtually no new building projects, leaving large parts of the college housed in buildings which were not fit for purpose.[18] Kenneth Baxter has claimed that World War I had a major impact on University College and stated that the conflict presented it with "a storm of challenges unlike anything it had faced" up to that point.[19] Baxter contends that the War impacted the college greatly, with key consequences being declining student numbers which in turn led to a loss of income, as well as staff departures and the decaying of fabric.[20] In 2018 it was revealed that research shows that while the college's war memorial records the names of 37 staff and former students who died at least a further 39 alumni of the college were not recorded on it.[20][21] In 1920 the college received a war trophy in the form of a "40 ton, 15 cm field gun", which was thought to have been captured from Bulgarian forces and was sited in front of the students Union.[22]

Attempts were made to raise income. In 1923 Rudyard Kipling, then the rector of the University of St Andrews, visited University College and asked the merchant princes and leading citizens of Dundee to give the college their money and support. Kipling implored those who had lost their sons in the Great War to consider giving a donation so that their names would live on.[23] Staff of a high calibre continued to be employed by the university including Alexander Peacock and Margaret Fairlie, who in 1940 was appointed as professor of obstetrics and gynaecology and thus became the first woman to hold a professorial chair at a university in Scotland.[18][24]

In 1947, the principal of University College, Douglas Wimberley released the "Wimberley Memo" (resulting in the Cooper and Tedder reports of 1952), advocating independence for the college. In 1954, after a royal commission, University College was renamed "Queen's College" and the Dundee-based elements of the university gained a greater degree of independence and flexibility. It was also at this time that Queen's College absorbed the former Dundee School of Economics as well as the jointly administered medical school and dental school.[13]

Creation of the University of Dundee

[edit]

The publication of the Robbins Report on Higher Education in 1963, which considered the question of university education expansion throughout the country, provided impetus to the movement to attain independent university status for Dundee. At this time, a number of new institutions were being elevated to this status, such as the University of Stirling, and second universities were created in Edinburgh and Glasgow (Heriot-Watt University and the University of Strathclyde) despite their having fewer than 2,000 students.[6]

Queen's College's size and location, alongside a willingness to expand, led to an eventual decision to separate from the wider University of which it remained an integral part. In 1966, St Andrews University Court and the Council of Queen's College submitted a joint petition to the Privy Council seeking the grant of a royal charter to establish the University of Dundee. This petition was approved and the Charter was granted which saw Queen's College become the University of Dundee, on 1 August 1967. The university continued a number of the traditions of its originator college and university and continues to be organised under the ancient university governance structure.[25]

Modern developments

[edit]

In 1974, the university began to validate some degrees from Dundee's Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, and by 1988 all degrees from that institution were being validated in this fashion. In 1994 the two institutions merged, with the college becoming a constituent faculty of the university.[26] In 1996, the Tayside College of Nursing and the Fife College of Health studies became part of the university, as a school of Nursing and Midwifery.[27] For several years, Dundee College of Education prepared students for degree examinations at the University of Dundee, and in December 2001 the university merged with the Dundee campus of Northern College to create a Faculty of Education and Social Work.[28]

In October 2005, the university became home to the first UNESCO centre in the United Kingdom. The IHP-HELP Centre for Water Law, Policy and Science is involved in research regarding the management of the world's water resources on behalf of the United Nations.[29] A school of accounting and finance was introduced in 2007. These disciplines are now part of the School of Business.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the university suspended most face to face teaching from 16 March 2020. However, a "blended learning" approach was offered to many students with weekly tutorials available in person for small groups using COVID-19 protocols of social distancing and regular cleaning.[30]

Campus

[edit]City Campus

[edit]

The main campus is within the West End of the City of Dundee.[31] It has expanded greatly since the university gained independence, from just four converted buildings when the University College was founded in 1881 the university has grown to consist of over fifty at present. However, many buildings survive from Dundee's period as a university college and as a constituent college of St Andrews University. The earliest purpose-built facility on campus was the Carnelley Building which opened in 1883 as part of the new University College.[32] A £10,000 donation from Mary Ann Baxter provided for a chemistry laboratory situated in the building which was named for the university's first professor of chemistry, Thomas Carnelley.[33]

Geddes Quadrangle

[edit]The buildings at the heart of the university form the Geddes Quadrangle. These include the Carnegie, Harris and Peters Buildings which were constructed in 1909 as part of the new college of the University of St Andrews.[34] The Geddes Quadrangle was named for Patrick Geddes, a pioneering thinker in the fields of sociology and urban planning and former professor of botany at Dundee, as a botanist Geddes had originally proposed a garden in the center of the quadrangle to be used for teaching purposes.[35] The designer was Victorian architect Robert Rowand Anderson, the architect of buildings such as the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and Mount Stuart House.[36]

Post-war buildings

[edit]Amid the expansion of education in post-war Britain, the University College, Dundee commissioned the construction of several new buildings to cope with the increasing numbers of students and academics arriving. The first of these was the Ewing Building which had started planning in 1950 and was officially opened in 1954. Named after Sir James Alfred Ewing, the university's first professor of engineering.[37][38] The Fulton Building gave the civil and mechanical engineering department a dedicated building, it was opened in 1964 and took its name from Angus Robertson Fulton, former principal of University College, Dundee (1939–1946).[39]

The 1960s saw the further development of the Queen's College campus with some of the earliest multi-story towers in Scotland being built for both teaching and student accommodation. The Tower Building, opened in 1961 by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, exemplified early Scottish modernist architecture and was designed by Robert Matthew; it stands 140 ft tall with ten storeys home to both academic, executive and administrative departments of the university.[40][41][42] The Tower was built on the site of two of the original four Georgian houses which had housed University College, Dundee (originally known as Whiteleys). Its construction was notable as it was the tallest structure built in Dundee since the Old Steeple in the medieval period. The building was extended in the later 1960s was resulted in the demolition of the remaining two original buildings.[42]

Belmont Halls of Residence took inspiration from Danish design and aimed to provide modern, spacious quarters for students while keeping costs cheap; it was completed in 1963 on the site of Belmont Works, a former jute mill.[43]

Recent developments

[edit]The 2000s brought extensive renovation to the university's central campus, with a number of new and upgraded buildings introduced around 2007 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the university's independence. Large extensions have been placed on the Main Library and sports centre, and a number of new halls of residence (Heathfield, Belmont, West Park and Seabraes) have been gradually phased into operation.[44][45] The Dalhousie building was erected during this period as dedicated teaching accommodation for the university, in part replacing space previously at the Gardyne Road campus of Northern College, which has now been taken up by Dundee College. Significant improvement works have taken place in old buildings such as the Old Technical Institute, Medical Sciences Institute and Old Medical School buildings.[46]

Kirkcaldy Campus

[edit]The School of Nursing and Health Sciences has a campus on Forth Avenue, Kirkcaldy, Fife.[47][48] This offers degrees in nursing, midwifery and other health-related subjects. Placements are available often in conjunction with NHS Fife.

Governance and organisation

[edit]Governance

[edit]

The University of Dundee is organised under the provisions of its royal charter, which granted the university its independence in 1967.[25] Dundee, uniquely outside of the four ancient universities of Scotland has a governance framework which shares a number of similarities with the ancient governance structure which was developed in the 19th and 20th centuries through the various Universities (Scotland) Acts.

Chancellor

[edit]The chancellor is the head of the university and president of the Graduates' Council, with a role of presiding over academic ceremonies such as graduations.[49] The six chancellors of the university to have held office since its independence are:

- Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother (1967–1977)

- Simon Ramsay, 16th Earl of Dalhousie (1977–1992)

- Sir James W. Black (1992–2006)

- Narendra Patel, Baron Patel (2006–2017)

- Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell (2018–2023)[50]

- Baron George Robertson (2023-)[51]

Rector

[edit]

The rector of the university is an official elected by the matriculated students of the university for a three-year term.[52] In common with other university rectors in Scotland, the position is largely ceremonial, although it does involve the representation of students on the University Court. The rector at Dundee, unlike that of the ancient universities, does not chair the University Court, that duty instead falling to a lay member.[53] The rector may appoint an assessor who can carry out the rector's functions on their behalf when they are absent. The university gained national attention in 2001 when it seemed that actor David Hasselhoff may stand as rector.[54]

As part of the process of installation, the students traditionally take the new rector on the 'rectorial drag' which involves them being 'dragged' from Dundee City Chambers to the university in the university's own carriage visiting on the way some of the many pubs in the city as part of the informal welcome to the university.[55]

The present holder of the position is artist manager Keith Harris, who was installed in 2022.[56] He replaced sports broadcaster Jim Spence, who was installed in 2019 but did not serve a full term partly due to changes in personal circumstances as a result of COVID-19.[57] Prior to Spence, the rector was Mark Beaumont, the record-breaking endurance cyclist.[58]

Previous Rectors since the university's independence have included Sir Peter Ustinov, Sir Clement Freud, and Stephen Fry, who each served two terms, and Craig Murray, Tony Slattery, Lorraine Kelly and Fred MacAulay, who each served one.[59][60]

Principal and Vice-Chancellor

[edit]The Principal and Vice-Chancellor is the chief academic and administrative officer of the university, presiding over the Senatus Academicus.[62] As a result of their title as Vice-Chancellor, the Principal can fulfill the duties of the Chancellor in their absence. Prior to the university's independence, when it was part of the University of St Andrews, a similar function was carried out by the Master of Queen's College. This position replaced the earlier post of principal of University College, Dundee, which was first filled in 1882.

Following the announced resignation of Principal and Vice-Chancellor Sir Pete Downes in February 2018, the university appointed Professor Andrew Atherton to the post, to begin in January 2019.[63] Atherton resigned following a dispute with the university in November 2019.[64]

Holders of this position and its predecessors are:

Principals of University College, Dundee

[edit]

- William Peterson (1882–1895)

- John Yule Mackay (1895–1930)

- Sir James Irvine (1930–1939) – 'Interim' appointment[65][66]

- Angus Robertson Fulton (1939–1946) – 'Interim' appointment[65][66]

- Douglas Wimberley (1946–1954)

Masters of Queen's College, Dundee

[edit]- David Rutherford Dow (1954–1958)

- Arthur Alexander Matheson (1958–1966)

- James Drever (1966–1967)

Principals of the University of Dundee

[edit]- James Drever (1967–1978)

- Adam Neville (1978–1987)[65]

- Michael Hamlin (1987–1994)[65]

- Ian James Graham-Bryce (1994–2000)

- Sir Alan Langlands (2000–2009)[65][67]

- Sir Pete Downes (2009–2018)[68][69]

- Andrew Atherton (2019)[69][64]

- David Maguire (2020) Interim Principal[70]

- Iain Gillespie (2021-) [71]

Structure

[edit]As of 1 August 2022, the University of Dundee is organised into eight schools containing multiple disciplines.[72] Each individual school is formally headed by a dean. The following is a full list of the academic divisions of the university:

|

School of Art and Design School of Business

School of Dentistry

|

School of Life Sciences School of Medicine School of Health Sciences

School of Science and Engineering[73]

|

|

-

The Scrymgeour Building, which houses Law, Psychology and Politics

-

The Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design

-

The Ewing Building, home to research forensics and Estates and Campus Services.

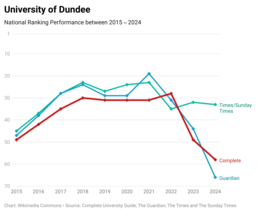

Rankings

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[74] | 52= |

| Guardian (2025)[75] | 52 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2025)[76] | 36 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[77] | 401–500 |

| QS (2025)[78] | 418= |

| THE (2025)[79] | 301–350 |

University rankings

[edit]As of 2024[update], Dundee is ranked within the top 500 universities in the world according to the major global rankings (Times, CWTS Leiden, QS, and ARWU); placing 301-350th in the Times World University rankings, joint 409th in the CWTS Leiden Ranking, joint 441st in the QS World University Rankings and 401-500th in the Academic Ranking of World Universities. The university was The Times Good University Guide's "Scottish University of the Year" consecutively in 2015/16 and 2016/17.[80]

Subject rankings

[edit]In both the 2021 and 2014 Research Excellence Framework which assesses research output between 2008-2020, the quality of research for Biological Sciences at Dundee is ranked 2nd in the United Kingdom by GPA, behind only the specialist Institute of Cancer Research.[81] According to the 2024 Times Higher Education World University Rankings by Subject, Dundee's strongest subjects are Life Sciences, ranked in the top 125 in the world[82] and Law, ranked in the top 150 in the world.[83] The 2023 QS World University Rankings by Subject ranks the university in the top 200 in the world for Pharmacy & Pharmacology, Biological Sciences, Art & Design, Nursing, and Medicine. [84]

In the 2024 Guardian university rankings in the UK, Dundee's subject offerings in Dentistry (3rd in UK, 1st in Scotland), and Computer science and information systems (9th in UK, 3rd in Scotland) rank within the top ten nationally.[85] In 2023/2024 Anatomy & Physiology, Art and Design, Biological Sciences, Social Work and Medicine rank within the top ten nationally in at least one of the rankings.[86]

Student life

[edit]

|

| Domicile[90] and Ethnicity[91] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| British White | 66% | ||

| British Ethnic Minorities[b] | 11% | ||

| International EU | 5% | ||

| International Non-EU | 18% | ||

| Undergraduate Widening Participation Indicators[92][93] | |||

| Female | 66% | ||

| Private School | 10% | ||

| Low Participation Areas[c] | 16% | ||

Students at Dundee are represented by the university's students' representative council and the Rector in common with other universities in Scotland sharing the ancient organisational structure.

Students' Association

[edit]

The Dundee University Students' Association (DUSA), unlike many other students' unions in the United Kingdom, is not affiliated to the National Union of Students, mainly due to cost concerns and political objections.

Membership of the Students' Association is automatic for all students of the university, although it is possible under statutes to renounce this membership at any time. The Association, as with the other ancient universities in Scotland, co-exists with the University's students' representative council.

The DUSA building is located in Airlie Place, in the centre of the University's Main Campus and caters as a private members' club offering bar, nightclub and refectory services for students.[94] DUSA also provides a number of other typical students' union services such as advocacy on behalf of its membership and assistance to individual students. In addition the DUSA facilitates the creation of student societies, as of 2023 there are 240 student-led societies on campus.

Sports facilities

[edit]As of 2016, there are 43 clubs affiliated with the Sports' Union. There is an annual award ceremony for the sports clubs, and a Blues & Colours Ball (see Blue (university sport)) to provide social interaction between the clubs.

The Institute of Sport and Exercise, unlike the Sports Union, is directly controlled by the university, but works closely with the students' organisations. Its chief building is located on Old Hawkhill in the main campus, which contains the main indoor sporting facilities and the university's gym.

Outdoor facilities are mainly based in the Riverside Sporting Ground, within a reasonable walking distance and bordering the Tay, although there are others – such as tennis courts – spread throughout the main campus. The ISE's 25m swimming pool is located within the Students' Association building on Airlie Place.

Notable sporting achievements of the university include winning the British University Gaelic football Championship in 1994 and being the first team in Scottish rugby history to win the league and SUS Cup double in the 2007/08 season.[citation needed]

Chaplaincy

[edit]The University Chaplaincy Centre was constructed in 1974 and extended in 1987 and houses both the University Chapel and a number of other related social facilities.

The university has a full-time chaplain, Fiona Douglas (since 1997), who is a minister of the Church of Scotland. There are also several part-time associate and honorary chaplains representing other faiths and denominations.

Traditions

[edit]Dundee students participate in a number of traditional events during the academic calendar. Towards the start of the year, a standard British Freshers' Week is organised, with a secondary one held when the university reconvenes after the Christmas vacation.

Traditions remaining from Dundee's days as a college of the University of St Andrews include the Gaudie Night (taking its name from the first line of the students' anthem, De Brevitate Vitae) – held early in the first semester and organised both as a Students' Union night and an event organised by the individual schools (for example by the Life Sciences, Medical, Law and Dentistry Societies) where students are assigned academic "parents" from the senior years. Some weeks later, a Raisin (alternatively spelled "Raisen") weekend is held to all new students to repay their academic parents' hospitality. Generally the school society run events are more traditional in nature than the Students' Union event.

Since 2004, the university has organised the Discovery Days series of public lectures hosted by University and visiting academics and persons of note, providing introductions into a number of major fields of work taking place at Dundee.

Student residences

[edit]

The university has a number of student residences spaced around the city. Over the last decade there has been an attempt to move some of these halls of residence closer to the main campus. With the closure and re-building of West Park Hall in 2005, all of the halls are now self catered en-suite.

At present, there exist the following university residences:

- Belmont Tower (including Belmont Upper/Lower) – Based on the main campus and consisting of two main sections: Belmont Tower, opened in 1966, located on Mount Pleasant next to Belmont Quadrangle; and Belmont Upper and Lower, a long and low building connected to the tower, raised up on stilts to accommodate for car parking underneath for residences staff.

- Belmont Flats – Opened in 2006, these halls are of identical style to those of Heathfield and the new Seabraes halls. It is located on Old Hawkhill, across from the ISE and centred around Belmont Quadrangle.

- Heathfield – Built at the same time as Belmont Flats. It is located on Old Hawkhill, immediately across from Belmont Tower.

- Seabraes – A number of buildings containing flats, with a new hall identical in style to the new Heathfield and Belmont Halls being built at the foot of the complex. Located near to the south side of the main campus on Roseangle.

- West Park – Located some distance to the west of the main campus, these halls were traditionally popular with medicine students due to their proximity to Ninewells Hospital. Consists of a relatively new complex known as West Park Villas, which are essentially student flats. The old hall (separate from the Villas) was largely torn-down in 2005 (leaving behind only the listed parts of the building) and the new complex (generally known as 'West Park Flats' by the university) will be available from the start of the 2007/08 term.

Some older halls, despite remaining open in the interim until building works were finished, are now out of use – the last students moved out in early 2007. These are:

- Airlie Place & Springfield – A number of flats located in old terrace housing on the main campus, consisting of two streets mainly owned by the university. Both are architecturally noteworthy and have mostly been converted to offices.

- Peterson Hall – An almost brutalist style building to be found further down Roseangle from Seabraes. This hall was traditionally a non-smoking hall of residence, and is now ear-marked for private development.

- Wimberley Houses – The furthest university residences from the main campus, Wimberley – also the closest to Ninewells Hospital in the far west of the city. The residences themselves were a complex of buildings, each comprising a "house" which served as an independent flat for a number of students. They were named for Principal Douglas Wimberley.

Historic collections

[edit]The university's cultural and historic collections are looked after by Museum Services and Archive Services.

Museum Services

[edit]

Dundee has significant museum collections acquired over the 140 years of its history. These include fine art, design furniture, textiles, scientific instruments, medical equipment and natural history specimens. The collections are accredited as a public museum and are cared for by Museum Services.[95] In 2012 it was announced that Museum Services had been awarded a grant of £100,000 by the Art Fund to develop an art collection inspired by D'Arcy Thompson.[96][97] This body promotes the various departments of the university involved in cultural activity and runs an annual culture day of short public lectures.[98][99] In January 2014 it was announced that Museum Services had been awarded funding of £32,407 to acquire a new object database to aid the management of its various collections of nearly 30,000 items.[100]

Archive Services

[edit]The university's Archive Services was established in 1976[101] and maintains the University of Dundee's manuscripts and records collections. The archives hold a wide range of material relating to the university and its predecessor institutions and to individuals associated with the university. Archive Services also holds a number of records relating to individuals, businesses and organizations based in the Tayside area.[102] The records held include a substantial number of business archives relating to the jute and linen industry in Dundee and West Bengal, records of other businesses including the archives of the Alliance Trust and the department store G. L. Wilson, the records of the Brechin Diocese of the Scottish Episcopal Church, the Michael Peto photographic collection and the NHS Tayside Archive.[103][104] Archive Services' other collections include the archives of Dundee Repertory Theatre[105] and the papers of the Great War poet Joseph Johnston Lee.[106] In addition to material relating to the local area, the archives have a number of documents relating to other countries, especially India.[107] The Archives also hold the records of the Glasite Church.[108][109][110]

The archives also house some special book collections. These include rare books relating to local history and the Joan Auld Memorial Collection, an important collection of labour history books donated to the university in 1996 in memory of Joan Auld, the first university archivist, who had died in a climbing accident the previous year.[111][112][113]

Archive Services also runs an ongoing oral history project to record the memories of individuals who have lived and worked in Dundee and hold public events to promote the project.[114]

Notable alumni and staff

[edit]-

Sir James Alfred Ewing, physicist noted for his discovery of hysteresis

-

Margaret Fairlie, gynaecologist and Scotland's first female professor

-

B.C. Forbes, financial journalist and founder of Forbes magazine

-

Sir Patrick Geddes, pioneering town planner and sociologist

-

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, engineer known for his work in radar technology

This list includes certain persons who are graduates of the University of St Andrews, having studied at the University College or Queen's College in Dundee, as well as graduates of the University of Dundee. This is a result of the incorporation of this institution in the other from 1897 to 1967. Indeed, in a great many respects, the medical school at the University of Dundee is the direct inheritor of the medical traditions of the University of St Andrews. It also includes notable former members of staff of these institutions.[115][116]

Former chancellor Sir James Black, who had studied medicine at the then University College Dundee, won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his work on the discovery of propranolol – a beta-blocker for the treatment of hypertension. Ronald Coase served as a founding lecturer from 1932 to 1934 of the Dundee School of Economics and Commerce. Coase received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1991 for his work on the significance of transaction costs and property rights for the institutional structure and functioning of the economy.

Business and economics

[edit]- Ahmed Adamu, Nigerian economist and first global chairperson of the Commonwealth Youth Council

- Sir Robert Horton, former chairman of BP and Railtrack

- Sir George Mathewson, Chairman of the Royal Bank of Scotland Group (2001–2006); Convenor of the Scottish Council of Economic Advisers (2007–2011)

- Sanusi Ohiare, Nigerian economist and former executive director of Nigeria's Rural Electrification Fund (2017-2023)

Law

[edit]Media and the arts

[edit]- Johanna Basford, illustrator[117]

- Naetochukwu Chikwe (Naeto-C), musician

- B. C. Forbes, founder of Forbes magazine

- Holly Hamilton, BBC journalist and presenter[118]

- David Jackson, musician, best known for his involvement in Van der Graaf Generator

- Alan Johnston, BBC correspondent based in Gaza, famously kidnapped in 2007

- Gary Lightbody, lead singer of Snow Patrol

- Fred MacAulay, comedian and former rector of the university

- James McIntosh, food writer

- Graham Phillips, pro-Kremlin journalist covering the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Karine Polwart, folk musician

- Carla Romano, GMTV reporter

- John Suchet, Channel Five news anchor, formerly of ITN

Artists

[edit]- Calum Colvin

- Luke Fowler, 2012 Turner Prize Nominee

- David Mach, 1988 Turner Prize Nominee

- Lucy McKenzie

- Susan Philipsz, 2010 Turner Prize

- Thomson & Craighead

- Louise Wilson (of Jane and Louise Wilson) 1999 Turner Prize Nominees

Politics

[edit]- John Peter Amewu, Member of Parliament, Parliament of Ghana; and Minister for Railways Development, Ghana

- Malcolm Bruce, former Liberal Democrat Member of Parliament, Rector of the university (1986–89)

- Christopher Chope, Member of Parliament, former Minister of State and barrister

- Lynda Clark, Baroness Clark of Calton, former member of parliament and Advocate General for Scotland, now Senator of the College of Justice

- Chris Clarkson, Conservative member of parliament

- William Cullen, Baron Cullen of Whitekirk, advocate, judge, Lord Justice General and Lord President of the Court of Session as well as life peer

- Kurt Deketelaere, secretary-general of the League of European Research Universities

- Frank Doran, former Labour member of parliament

- Kevin Dunion, Scottish Information Commissioner between 2003 and 2012, as well as former Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews

- Maurice Golden, Conservative member of the Scottish Parliament

- Boaz Kipchumba Kaino, former MP and assistant minister of lands and settlement. Republic of Kenya

- Geoffrey Aori Mabea, first executive secretary of the Energy Regulators Association of East Africa

- Finlay Macdonald, retired minister and principal clerk to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

- Jenny Marra, member of Scottish Parliament, attended Dundee to read the Diploma in Professional Legal Practice

- Paul Masterton, former Conservative MP and solicitor

- Bruce Millan, Labour MP, Secretary of State for Scotland and European Commissioner for Regional Policy

- Lewis Moonie, Baron Moonie – Labour politician, former minister of state

- Claude Moraes, former Commissioner for Racial Equality, former member of the European Parliament

- Craig Murray, former British ambassador to Uzbekistan, former president of DUSA, former rector of the university

- Elijah Ngurare, Namibian politician serving as the secretary general of the SWAPO Party Youth League

- Nhial Deng Nhial, Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Republic of South Sudan

- Alex Neil, Scottish National Party MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Health and Wellbeing

- George Robertson, Baron Robertson of Port Ellen, former Secretary-General of NATO, Labour MP and UK Secretary of State for Defence

- John Stevenson, Conservative MP and solicitor

- Brian Wilson, former Labour MP and Minister of State

Science, medicine and engineering

[edit]- Sir James W. Black, pharmacologist and Nobel laureate

- Sue Black, anatomist and forensic anthropologist

- William Thomas Calman, zoologist

- Richard A. Collins, scientist and author

- Jane Eddleston, medical doctor, professor and critical care expert

- Sir James Alfred Ewing, engineer and physicist

- Margaret Fairlie, gynaecologist and first female professor in Scotland[24][119]

- Thomas Claxton Fidler, civil engineer

- Angus A. Fulton, civil engineer

- Sir Patrick Geddes, biologist, botanist and urban planning theorist

- Johannes Kuenen, physicist

- Peter LeComber, physicist

- Doris Mackinnon, zoologist

- Narendra Patel, obstetrician, former chancellor of the university

- Alexander David Peacock, zoologist

- William Peddie, mathematician and physicist

- Harold Plenderleith, art conservator and archaeologist

- George Dawson Preston, physicist

- Dorothy MacBride Radwanski, occupational health nurse

- Edward Waymouth Reid, physiologist

- William G. Smith, botanist and ecologist

- Walter Eric Spear, physicist

- John Steggall, mathematician

- Sir William Stewart, government chief scientific advisor

- D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, biologist, mathematician, and classical scholar

- A. D. Walsh, chemist

- Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, pioneer of radar

- William Alexander Young, doctor, surgeon and epidemiologist

- Isham Jaafar, Minister of Health in Brunei Darussalam[120]

Miscellaneous

[edit]- Colin Norris, serial killer nurse who is believed to have been inspired by lectures at the university in 2001 to kill his patients[121][122]

- David Shayler, Security Service officer who revealed state secrets to the public, editor of Annasach magazine while at the university

- Cardinal Cornelius Sim, Roman Catholic Bishop of the Apostolic Vicariate of Brunei Darussalam

See also

[edit]- Armorial of UK universities

- University of Dundee Botanic Garden – University gardens in the West End of the city.

- List of universities in the United Kingdom

Notes

[edit]- ^ Scottish Gaelic: Oilthigh Dhùn Dè; [ˈɔlhɪj ɣun ˈtʲeː]. Abbreviated as Dund. for post-nominals.

- ^ Includes those who indicate that they identify as Asian, Black, Mixed Heritage, Arab or any other ethnicity except White.

- ^ Calculated from the Polar4 measure, using Quintile1, in England and Wales. Calculated from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) measure, using SIMD20, in Scotland.

References

[edit]- ^ The motto is taken from the first line of the Magnificat, a prayer offered by Mary, mother of Jesus, the Patron Saint of the City of Dundee.

- ^ a b c "Financial Statements July 2023". University of Dundee. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Chricton, Emma (20 August 2020). "The Courier". DC Thomson Ltd. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Who's working in HE?". www.hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ a b c "Where do HE students study? | HESA". hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ a b c "History of the University". Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Kenneth Baxter (2018). "University College, Dundee and the Great War". In Kenefick, William; Patrick, Derek (eds.). Tayside at War. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society. p. 83 (footnote 1). ISBN 978-0-900019-65-4.

- ^ "Student lists". Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ University of St Andrews Calendar 1894. 1894. p. 28. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Baxter, Kenneth (8 March 2013). "International Women's Day". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Baxter, Kenneth (2010). ""Matriarchal" or "Patriarchal"? Dundee, Women and Municipal Party Politics in Scotland c.1918-c.1939". International Review of Scottish Studies. 35: 99. doi:10.21083/irss.v35i0.1243. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "MS 31 Dr Ruth Young". Archive Services Online Catalogue. University of Dundee. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ a b "University College, Dundee and Queen's College". Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "100 years ago..." Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "St. Andrews University And Dundee College". The British Medical Journal. 1 (1797): 1274–1276. 1895. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 20216435. PMC 2510094. PMID 20755582.

- ^ Deed of Endowment

- ^ "Scotland in the 19th century: Section 5.9: Universities [ebook chapter] / J A Haythornthwaite, 1993". Gdl.cdlr.strath.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ a b Baxter, Kenneth, Rolf, Mervyn, and Swinfen, David (2007). A Dundee Celebration. Dundee: University of Dundee. p. 10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kenneth Baxter (2018). "University College, Dundee and the Great War". In Kenefick, William; Patrick, Derek (eds.). Tayside at War. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-900019-65-4.

- ^ a b Kenneth Baxter (2018). "University College, Dundee and the Great War". In Kenefick, William; Patrick, Derek (eds.). Tayside at War. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society. pp. 75–83. ISBN 978-0-900019-65-4.

- ^ "Number of fallen WW1 soldiers from Dundee University may be double what previously thought". Evening Telegraph. DC Thomson & Company Ltd. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ Michael Taylor (2018). "'Bristling with guns'- German First World War Artillery in Tayside and Fife, 1919-1940". In Kenefick, William; Patrick, Derek (eds.). Tayside at War. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-900019-65-4.

- ^ "J M Barrie and Rudyard Kipling". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. 29 March 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Notable University Figures (3): Professor Margaret Fairlie". Archives, records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ a b "University of Dundee Charter" (PDF). University of Dundee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design". Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "A brief history of the School of Nursing & Midwifery". Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "A History of Dundee College of Education". Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Centre for Water Law, Policy and Science". University of Dundee. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Announcements. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update for students – suspension of face-to-face teaching". University of Dundee. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "University of Dundee Campus map". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Stuff, Good. "Park Place, Carnelley Building, University of Dundee, Including Boundary Walls, Dundee, Dundee". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Carnelley Building, University of Dundee". Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ "The Carnegie Building, University of Dundee". Scran. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Geddes Quadrangle, University of Dundee". Scran. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Architecture, University of Dundee". Scran. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Ewing Building, University of Dundee". Scran. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Notable Figures". University of Dundee Archives. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Fulton Building, University of Dundee". Scran. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Tower Building, University of Dundee". Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ "The Tower Building Outlook City". Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ a b McKean, Charles; Whatley, Patricia; with Baxter, Kenneth (2013). Lost Dundee. Dundee's Lost Architectural Heritage (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 191–193.

- ^ "Belmont Halls, University of Dundee". Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ Dundee, University of. "Current Project Status, University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Campus map - University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Old Medical School & Carnelley Building". Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "University of Dundee - Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "A brief history of the School of Nursing : Museum : University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Royal Charter, s.4.1

- ^ Dundee, University of. "Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell Appointed Chancellor of the University of Dundee : News". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "George Robertson Appointed Chancellor of the University of Dundee". Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ Royal Charter s.5

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Baywatch star sinks student hopes". BBC News. 1 February 2001.

- ^ "Adventurer Mark Beaumont installed as new Dundee University rector". BBC News. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ "Keith Harris to be installed as University Rector". University of Dundee. 20 April 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Keith, Jake (23 March 2021). "Broadcaster Jim Spence announces he will step down as Dundee University rector". The Courier. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Jim Spence installed as Dundee University rector". 9 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Baxter, Kenneth; et al. (2007). A Dundee Celebration. Dundee: University of Dundee. p. 61.

- ^ "Rectorial Elections". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Stephen Fry | One Dundee". blog.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Royal Charter, s.6.1(a)

- ^ "Dundee University appoints new principal". BBC News. 2 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Rent row Dundee University principal Andrew Atherton quits". BBC News. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Baxter, Kenneth; et al. (2007). A Dundee Celebration. Dundee: University of Dundee. p. 60.

- ^ a b Shafe, Michael (1982). University Education in Dundee: A Pictorial History. Dundee: University of Dundee. p. 201.

- ^ "New Principal welcomes freshers". Press Release Archive. University of Dundee. 29 September 2000. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Professor Pete Downes – Principals Office – The University of Dundee". Dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ a b Isles, Roddy (2 July 2018). "Professor Andrew Atherton appointed Principal & Vice-Chancellor". University News. University of Dundee. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Professor David Maguire appointed Interim Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Dundee". University of Dundee press releases. University of Dundee. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Richards, Xander (25 August 2020). "Dundee University appoints new principal after last boss quit in rent row". The National. Newsquest. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "University of Dundee list of Academic Schools". University of Dundee. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ "School of Science and Engineering | University of Dundee, UK".

- ^ "Complete University Guide 2025". The Complete University Guide. 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Guardian University Guide 2025". The Guardian. 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Good University Guide 2025". The Times. 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2024". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 15 August 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. 4 June 2024.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings 2025". Times Higher Education. 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Dundee is Scottish University of the Year – again!". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "REF 2021: Biological sciences". Times Higher Education. 12 May 2022.

- ^ "World University Rakings 2023 by subject: life sciences". Times Higher Education. 28 October 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "World University Rakings 2024 by subject: law". Times Higher Education. 28 October 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Subject rankings 2023 - Top Universities". Top Universities. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ "Guardian Subject Rankings 2024 – University of Dundee". Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ HitCreative. "The Times and The Sunday Times | Education - UniversityGuide". st.hitcreative.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ a b "UCAS Undergraduate Sector-Level End of Cycle Data Resources 2023". ucas.com. UCAS. December 2023. Show me... Domicile by Provider. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "2023 entry UCAS Undergraduate reports by sex, area background, and ethnic group". UCAS. 30 April 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "University League Tables entry standards 2024". The Complete University Guide.

- ^ "Where do HE students study?: Students by HE provider". HESA. HE student enrolments by HE provider. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Who's studying in HE?: Personal characteristics". HESA. 31 January 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Widening participation: UK Performance Indicators: Table T2a - Participation of under-represented groups in higher education". Higher Education Statistics Authority. hesa.ac.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Good University Guide: Social Inclusion Ranking". The Times. 16 September 2022.

- ^ "DUSA The Union (The Union, Dundee University, Airlie Place, Dundee) | The List". www.list.co.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Museum : Museum : University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Museum Services wins £100,000 Art Fund Grant". E-ARMMS Newsletter 11. January 2012. University of Dundee. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ "D'Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum RENEW Project". University of Dundee. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ "Culture Day is on its way". Archives Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Culture & Arts Forum". Museum Services. University of Dundee. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "News from ARMMS". University of Dundee.

- ^ "Archives : University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "University of Dundee Archives Services". University of Dundee. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "University of Dundee Archives Services the Collections". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Business Archives". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "MS 316 Dundee Repertory Theatre". Archive Services Online Catalogue. University of Dundee. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "MS 88 Joseph Johnston Lee". Archive Services Online catalogue. University of Dundee. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "International Source List". University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ "MS 9 The Glasite Church". Archive Services Online Catalogue. University of Dundee. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "A New Glasite Accession". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "International Archives Day". Archives, Records and Artefacts at the University of Dundee. University of Dundee. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "Archive Services Online Catalogue". University of Dundee. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Auld, Joan – Archivist. 1938 – 1995". Dundee Women's Trail. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Special Collections". Archive Services Culture & Information. University of Dundee. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Oral History Project". Archive Services. University of Dundee. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Notable Scientists at Dundee University : Museum : University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Natures accounts : Museum : University of Dundee". www.dundee.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Rosanes, Kerby (8 May 2013). "Featured Artist: The Inky World of Johanna Basford". UCreative.com. UCreative Network. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ "Holly Hamilton". dontpanicspeakerbureau.com. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Baxter, Kenneth (2010). ""Matriarchal" or "Patriarchal"? Dundee, Women and Municipal Party Politics in Scotland c.1918-c.1939". International Review of Scottish Studies. 35: 99. doi:10.21083/irss.v35i0.1243.

- ^ "Minister of Health replaced". Rano360 Brunei.

- ^ Stokes, Paul (2 March 2008). "Colin Norris: From student to deadly abuser". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Failings allowed Leeds nurse Colin Norris to kill". BBC News. 26 January 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Bibliography

- Baxter, K., Rolfe, M. & Swinfen, D. A Dundee Celebration (Dundee: University of Dundee), 2007. The most recent history of the University of Dundee which was produced to mark the fortieth anniversary of the university's founding.

- Shafe, M. University Education in Dundee 1881–1981: A Pictorial History (Dundee: University of Dundee), 1982.

- Southgate, D., University Education in Dundee: A Centenary History (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 1982.

- White, R. M. "Dundee Law 1865-1967: The Development of a Law School in a Time of Change" (Dundee: Abertay Historical Society), 2019.

- Kenneth Baxter, "University College, Dundee and the Great War". In Kenefick, William; Patrick, Derek. Tayside at War.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to University of Dundee at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to University of Dundee at Wikimedia Commons