Mousetrap

A mousetrap is a specialized type of animal trap designed primarily to catch and, usually, kill mice. Mousetraps are usually set in an indoor location where there is a suspected infestation of rodents. Larger traps are designed to catch other species of animals, such as rats, squirrels, and other small rodents.

Types

[edit]Jaw mousetrap

[edit]

The trap that is credited as the first patented lethal mousetrap was a set of spring-loaded, cast-iron jaws dubbed "Royal No. 1".[1][2] It was patented on 4 November 1879 by James M. Keep of New York, US patent 221,320.[3] From the patent description, it is clear that this is not the first mousetrap of this type, but the patent is for this simplified, easy-to-manufacture design. It is the industrial-age development of the deadfall trap, but relying on the force of a wound spring rather than gravity.

The jaws are operated by a coiled spring, and the triggering mechanism is between the jaws, where the bait is held. The trip snaps the jaws shut, killing the rodent.

Lightweight traps of this style are now constructed from plastic. These traps do not have a powerful snap like other types. They are safer for the fingers of the person setting them than other lethal traps, and can be set with the press on a tab by a single finger or even by foot.

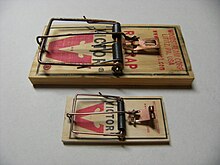

Spring-loaded bar mousetrap

[edit]

The spring-loaded mousetrap was first patented by William C. Hooker of Abingdon, Illinois, who received US patent 528671 for his design in 1894.[4][5] A British inventor, James Henry Atkinson, patented a similar trap called the "Little Nipper" in 1898, including variations that had a weight-activated treadle as the trip.[6][7]

In 1899, Atkinson patented a modification of his earlier design that transformed it from a trap that goes off by a step on the treadle into one that goes off by a pull on the bait.[8] The similarity of the latter design with Hooker's of 1894 may have contributed to a common mistake of giving priority to Atkinson.

It is a simple device with a heavily spring-loaded bar and a trip to release it. Cheese may be placed on the trip as bait, but other food such as oats, chocolate, bread, meat, butter and peanut butter are also used. The spring-loaded bar swings down rapidly and with great force when anything, usually a mouse, touches the trip. The design is such that the mouse's neck or spinal cord will be broken, or its ribs or skull crushed, by the force of the bar. The trap can be held over a bin and the dead mouse released into it by pulling the bar. In the case of rats, which are much larger than mice, a much larger version of the same type of trap is used to kill them. Some spring mousetraps have a plastic extended trip. The larger trip has two notable differences over the smaller traditional type: increased leverage, which requires less force from the rodent to trip it; and the larger surface area of the trip increases the probability that the rodent will set off the trap. The exact latching mechanism holding the trip varies, and some need to be set right at the edge in order to be sensitive enough to catch the mouse.

In 1899, John Mast of Lititz, Pennsylvania, filed a U.S. patent for a modification of Hooker's design that can be "readily set or adjusted with absolute safety to the person attending thereto, avoiding the liability of having his fingers caught or injured by the striker when it is prematurely or accidentally freed or released."[9] He obtained the patent on 17 November 1903. After William Hooker had sold his interest in the Animal Trap Company of Abingdon, Illinois, and founded the new Abingdon Trap Company in 1899, the Animal Trap Company moved to Lititz, Pennsylvania, and fused with the J.M. Mast Manufacturing Company in 1905. The new and bigger company in Lititz retained the name Animal Trap Company.[10] Compounding these different but related patents and companies may have contributed to the widespread mis-attribution of priority to Mast rather than Hooker.

Electric mousetrap

[edit]

An electric mousetrap delivers a lethal dose of electricity when the rodent completes the circuit by contacting two electrodes located either at the entrance or between the entrance and the bait. The electrodes are housed in an insulated or plastic box to prevent accidental injury to humans and pets. They can be designed for single-catch domestic use or large multiple-catch commercial use. See U.S. patent 4,250,655 and U.S. patent 4,780,985.

Live-capture mousetrap

[edit]

An early patented mousetrap is a live capture device patented in 1870 by W K Bachman of South Carolina.[11] These traps have the advantage of allowing the mouse to be released into the wild, or the disadvantage of having to personally kill the captured animal if release is not desired. To ensure a live capture, these traps need to be regularly checked as captured mice can die from stress or starvation. Captured mice need to be released some distance away, as mice have a strong homing instinct.[12] House mice tend to not survive long away from human settlements due to higher levels of predation.[13]

There are many methods to live trap mice. One of the simplest designs consists of a drinking glass placed upside down above a piece of bait, its rim elevated by a coin stood on edge. If the mouse attempts to take the bait, the coin is displaced and the glass traps the mouse.[14] Another method of live trapping, the bucket trap, is to make a half-oval shaped tunnel with a toilet paper roll, put bait on one end of the roll, place the roll on a counter or table with the baited end sticking out over the edge, and put a deep bin under the edge. When the mouse enters the toilet paper roll to take the bait, the roll (and the mouse) will tip over the edge and fall into the bin below; the bin needs to be deep enough to ensure that the mouse cannot jump out.[15]

A style of trap that has been used extensively by researchers in the biological sciences for capturing animals such as mice is the Sherman trap. The Sherman trap folds flat for storage and distribution and when deployed in the field captures the animal, without injury, for examination.

Glue mousetraps

[edit]

Glue traps are made using natural or synthetic adhesive applied to cardboard, plastic trays or similar material. Bait can be placed in the center or a scent may be added to the adhesive by the manufacturer. Glue traps are used primarily for rodent control indoors. Glue traps are not effective outdoors due to environmental conditions (e.g., moisture, dust), which quickly render the adhesive ineffective. Glue strip or glue tray devices trap the mouse in the sticky glue.

Glue traps often do not kill the animal so some people opt to kill the animal before disposing of the trap.[16] Manufacturers of glue traps usually state that trapped animals should be thrown away with the trap.

Because glue traps do not always kill the animal and often cause them to suffer a slow death, this method of trapping is denounced by animal rights groups and banned in several jurisdictions. Glue traps can be advantageous if the local population of animals have rat mites since the mite will remain on the animal's body while it is still alive and the glue would also trap mites leaving the animal after the animal's death.

Animals that come into contact with the trap can be released from the glue by applying vegetable oil and gently working the animal free. Glue traps are effective and non-toxic to humans.

Controversy

[edit]Death is much slower than with the traditional type trap, which has prompted animal activists and welfare organisations such as PETA and the RSPCA to oppose the use of glue traps.[17][18] Trapped mice eventually die from exposure, dehydration, starvation, suffocation, or predation, or are killed by people when the trap is checked. In some jurisdictions the use of glue traps is regulated. Victoria, Australia restricts the use of glue traps to commercial pest control operators, and the traps must be used in accordance with conditions set by the Minister for Agriculture.[19] Some jurisdictions have banned their use entirely;[20] in Ireland it is illegal to import, possess, sell or offer for sale unauthorized traps, including glue traps. This law, the Wildlife (Amendment) Act, was passed in 2000.[21] The use of glue traps to catch rodents without Ministerial approval has been prohibited in New Zealand since 2015.[22] Uncle Bob's Self Storage, the fifth-largest self storage company in the United States, has ended the use of these devices at all its facilities; other companies that have taken similar measures are ING Barings and Charles Schwab Corporation.[23]

Bucket mousetraps

[edit]Bucket traps may be lethal or non-lethal.[24] Both types have a ramp which leads to the rim of a deep-walled container, such as a bucket. The variations are many with some being single-catch and some multi-catch.[25]

The bucket may contain a liquid to drown the trapped mouse. The mouse is baited to the top of the container where it falls into the bucket and drowns. Sometimes soap or caustic or poison chemicals are used in the bucket as killing agents.

In non-lethal versions, the bucket is usually empty, allowing the mouse to live but keeping it trapped until the owner of the trap can release them.

Another design features a bowl (or similar container) containing a 1–2 centimetres (0.39–0.79 in) deep layer of vegetable oil, with a ramp leading up to the edge of the bowl. Mice, attracted by the oil's scent, climb in and become covered in the slippery oil, making it impossible for them to crawl or jump out.

In both cases, the unharmed mouse can be released outdoors. However, if several mice are caught simultaneously, and especially if the trap is subsequently left unchecked for several days before release, the mice may kill and eat each other to avoid starvation. To avoid this outcome, non-lethal multi-catch traps should be checked and emptied regularly.

Disposable mousetraps

[edit]There are several types of one-time use, disposable mousetraps,[26][27] generally made of inexpensive materials which are designed to be disposed of after catching a mouse. These mousetraps have similar trapping mechanisms as other traps, however, they generally conceal the dead mouse so it can be disposed of without being sighted. Glue traps are usually considered disposable – the trap is discarded with the mouse adhered to the trap.

Similar devices

[edit]

Similar ranges of traps are sized for to trap other animal species; for example, rat traps are larger than mousetraps, and squirrel traps are larger still. A squirrel trap is a metal box-shaped device that is designed to catch squirrels and other similarly sized animals. The device works by drawing the animals in with bait that is placed inside. Upon touch, it forces both sides closed, thereby trapping, but not killing, the animal, which can then be released or killed at the trapper's discretion.

History

[edit]A historical reference is found in Alciatis Emblemata[28] from 1534. The conventional mousetrap with a spring-loaded snap mechanism resting on a block of wood first appeared in 1884, and to this day is still considered to be one of the most inexpensive and effective mousetraps.[29]

In general culture

[edit]Reference to a mousetrap is made as early as 1602 in Shakespeare's Hamlet (Act III, scene 2), where it is the name given to the 'play-within-a-play' by Hamlet himself: "'tis a knavish piece of work", he calls it. There is a reference in the 1844 novel The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas, père. Chapter ten is titled "A Mousetrap of the Seventeenth Century". In this case, rather than referring to a literal mouse trap, the author describes a police or guard tactic that involves lying in wait in the residence of someone whom they have arrested without public knowledge and then grabbing, interviewing, and probably arresting anyone who comes to the residence. In the voice of a narrator, the author confesses to having no idea how the term became attached to this tactic.

The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer also references mouse traps in the prelude written sometime between 1387-1400. In the prelude introducing the Nun, Chaucer writes in lines 144-145, "She wolde wepe, if that she saugh a mous/Kaught in a trappe, if it were deed or bledde."

There is an earlier reference to a mousetrap, found in Ancient Greek The Battle of Frogs and Mice: "... by unheard-of arts they had contrived a wooden snare, a destroyer of Mice, which they call a trap.".[30]

A mousetrap (Spanish: ratonera) figures prominently in the second chapter of the 1554 Spanish novel Lazarillo de Tormes, in which the hero Lazarillo steals cheese from a mousetrap to alleviate his hunger.

Ralph Waldo Emerson is credited (apparently incorrectly) with the oft-quoted phrase advocating innovation: "Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door."

The Mousetrap is a popular play by Agatha Christie.

Mousetraps are a staple of slapstick comedy and animated cartoons. Episodes of the cartoon Tom and Jerry usually have plots based on Tom attempting to trap Jerry with different (and sometimes ridiculous) methods of trapping the mouse with a device realized as a Rube Goldberg machine, often being outsmarted by the latter and injuring himself in the process with the traps.

Mouse Trap (originally titled Mouse Trap Game) is a board game first published by Ideal in 1963 for two to four players. The game was one of the first mass-produced, three-dimensional board games. Over the course of the game, players at first cooperate to build a working Rube Goldberg-like mouse trap. Once the mouse trap has been built, players turn against each other, attempting to trap opponents' mouse-shaped game pieces.

Mousetraps loaded with table tennis balls or corks have been used to demonstrate the principle of a chain reaction.[31][32]

Mousetraps had become a subject of "challenges" on YouTube where people attempted to trigger them quickly with their hands, fingers or even tongue without getting trapped, as well as setting up multiple mousetraps as a prank. YouTubers Gavin Free and Daniel Gruchy created an experiment using a trampoline lined up with hundreds of mousetraps, triggered all at once by jumping into the trampoline, and recorded it in slow-motion.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cicciarelli, Rick. "Royal Cast iron mouse and rat traps". rickcicciarelli.com.

- ^ "Mouse Trap Exhibition - Dorking Museum & Heritage Centre". dorkingmuseum.org.uk.

- ^ "James m".

- ^ Patent of William C. Hooker's animal-trap Archived 31 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine in Google Patents.

- ^ "United States Patents: New York State Library". www.nysl.nysed.gov.

- ^ "Site with patent no. GB 27488 by Atkinson (1898)". Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Van Dulken, Stephen (2001). Inventing the 19th Century. New York University Press. pp. 128. ISBN 0-8147-8810-6.

- ^ "Site with patent no. GB 13277 by Atkinson (1899)". Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Patent of John M Mast (1903) improving the patent of Hooker (1894)". Retrieved 30 August 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "Drummond D., Brandt C & Koch J. (2002)". Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Improvement in mouse-traps".

- ^ Romano, Jay (17 January 1999). "YOUR HOME; The Mouse Checks In, But Not Out". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Tattersall F. H., Smith, R. H. & Nowell, F (1997). "Experimental colonization of contrasting habitats by house mice". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 62: 350–358.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gordon, Whitson (14 June 2011). "Make a No-Kill Mousetrap with a Jar and a Nickel". Lifehacker. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ "How to catch a mouse without a mousetrap". 20 September 2005.

- ^ "Rat Management Guidelines--UC IPM". www.ipm.ucdavis.edu.

- ^ "Glue Traps: Pans of Pain - PETA". peta.org. 21 June 2010.

- ^ "RSPCA policies on animal welfare" (PDF). 18 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ "New Regulations on the use of Glue Traps and other Rodent Traps, Government of Victoria, Australia, 2008" (PDF) (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2009.

- ^ "Animal Welfare Amendment Act 2008" (PDF). dpiw.tas.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ "Roche acts against illegal glue traps" (Press release). Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. 3 April 2006. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Glueboard traps prohibited from 2015". Ministry for Primary Industries. A New Zealand Government Department. New Zealand Government. 12 September 2020.

- ^ Robinson, David (12 June 2013). "PETA praises Sovran for glue trap ban". The Buffalo News. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ "Do-It-Yourself 'Better Mousetrap'". Bees, Bats and Beyond. Massachusetts Bee and Critter Removal Services. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010.

- ^ D. Gilmore, "A simple mouse trap." English mechanic and world of science, Volume XXXI. Page 185, item 17214. London:1880. Retrieved 20 August 2009

- ^ "Disposable mouse trap". 6 August 1990. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "A nice and easy way to catch mice". Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Alciato, Andrea (1534). "CAPTIVUS OB GULAM - caught by greed". Emblematum liber (in Latin).

- ^ Johnson, L. (21 August 2015). "How to Get Rid of Mice Naturally". Get Rid Talk. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica (lines 115–116) τὸν δ' ἄλλον πάλιν ἄνδρες ἀπηνέες ἐς μόρον εἷλξαν / καινοτέραις τέχναις ξύλινον δόλον ἐξευρόντες,

- ^ Agre, Peter (2011). "Life on the River of Science". Science. 331 (6016): 416–421. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..416A. doi:10.1126/science.1202341. PMID 21284129.

- ^ Sutton, Richard M. (1947). "A Mousetrap Atomic Bomb". American Journal of Physics. 15 (5): 427–428. Bibcode:1947AmJPh..15..427S. doi:10.1119/1.1990988.