Yi Yi

| Yi Yi | |

|---|---|

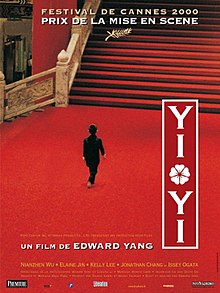

French theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Edward Yang |

| Written by | Edward Yang |

| Produced by | Shinya Kawai |

| Starring | Wu Nien-jen Elaine Jin Issey Ogata Kelly Lee Jonathan Chang Hsi-Sheng Chen Su-Yun Ko Lawrence Ko |

| Cinematography | Wei-han Yang |

| Edited by | Bo-Wen Chen |

| Music by | Kai-Li Peng |

| Distributed by | Kuzui Enterprises |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 173 minutes |

| Countries | Taiwan Japan |

| Languages | Mandarin Taiwanese Japanese English |

Yi Yi (Chinese: 一一; pinyin: Yī Yī; lit. 'one one'; subtitled A One and a Two) is a 2000 Taiwanese drama film written and directed by Edward Yang. It centers on the struggles of an engineer, NJ (played by Wu Nien-jen), and three generations of his middle-class Taiwanese family in Taipei.

The film's title means "one by one", or "one after another". When written in vertical alignment, the two strokes resemble the character for "two": 二.

Yi Yi premiered on May 14, 2000, at the 53rd Cannes Film Festival, where Yang won the Best Director Award.[1] The film has received acclaim and is often regarded as one of the greatest films of the 21st century.[2][3][4]

Plot

[edit]The Jian family—father NJ, mother Min-Min, daughter Ting-Ting, son Yang-Yang—is a middle-class family in Taipei. At the wedding of Min-Min's younger brother A-Di, NJ runs into his ex-girlfriend Sherry, who gives him her number before leaving. Sherry is married to an American and lives in Chicago. After the reception, Min-Min's mother, who lives with the family, suffers a stroke that leaves her comatose. She is put on life support and the doctor urges the Jians to talk to her daily.

NJ is dissatisfied with his job, and his company is struggling financially. To secure a client named Mr. Ota, NJ's colleagues ask him to take Ota out for dinner, to which he reluctantly agrees. They get along well and NJ takes Ota to a bar, where Ota sings and plays the piano. That night, NJ phones and leaves a message for Sherry, apologizing for leaving her abruptly 30 years ago. Meanwhile, Min-Min becomes depressed by her mother's condition and leaves for a remote Buddhist retreat.

After a failed investment, A-Di is kicked out of the house and asks his ex-girlfriend Yun-Yun for help. A-Di is allowed to return upon the birth of his child but a fight breaks out at the baby shower when Yun-Yun shows up uninvited. A-Di and his wife reconcile after she discovers him passed out due to a gas leak at their house.

Ting-Ting feels guilty because her grandmother collapsed while taking out the trash Ting-Ting was supposed to take out. She befriends her new neighbor, Lili. After Lili breaks up with her boyfriend Fatty, he begins to relay letters for Lili through Ting-Ting. Fatty soon becomes attracted to Ting-Ting and asks her out. After their second date, the two check into a hotel room, but they hesitate and leave. Later, Ting-Ting sees Lili back together with Fatty and is later berated by Fatty himself. Ting-Ting becomes depressed and talks to her grandmother, asking her to wake up. She learns the next day that Fatty has been arrested for killing Lili's teacher, who was in a sexual relationship with both Lili and her mother. At home, Ting-Ting dreams of being comforted by her grandmother.

Unwilling to speak to his grandmother because he feels like she cannot hear him, Yang-Yang starts taking photographs. To punish him for leaving school to buy film, Yang-Yang is forced to face a wall while his teacher circulates his photographs among the other students. Later, after seeing the girl who torments him (because she likes him) swimming, Yang-Yang teaches himself how to swim to learn more about his tormenter.

NJ is sent by his company to Tokyo to continue talks with Ota; Sherry also flies to Japan. The two reunite and recount their past; Sherry remains affected by NJ's abrupt departure and NJ attempts to resolve their tensions. They travel to another city and check into a hotel, but when NJ insists on separate rooms, Sherry berates him and breaks down. They return to Tokyo and check back into their respective rooms; before leaving, NJ tells Sherry that he has never loved anyone else. The next day, NJ is informed by his colleague that they have secured a deal with another client and he is to return to Taipei immediately. In response, NJ berates his colleague for abandoning Ota. Later, NJ goes to check on Sherry's room, learning that she has already checked out.

Upon her mother's death, Min-Min returns home and is reunited with her family. At the funeral, NJ's colleague urges him to come back to work, but he refuses. In front of her shrine, Yang-Yang recites an intimate monologue. He recounts their time together, his hope of finding where she went, and a desire to "tell people what they don't know, show them what they can't see." He concludes his poem by saying how his newborn cousin reminds him of her, always saying she is old, as he always wanted to say along with her, "I am old too."

Cast

[edit]- Wu Nien-jen as NJ

- Elaine Jin as Min-Min

- Kelly Lee as Ting-Ting

- Jonathan Chang as Yang-Yang

- Issey Ogata as Mr. Ota

- Chen Hsi-Sheng as A-Di

- Su-Yun Ko as Sherry

- Chang Yu Pang as Fatty

Production and casting

[edit]Yi Yi was filmed from April 8 to August 21, 1999. Yang's script originally had the children aged 10 and 15, but Yang later found Jonathan Chang and Kelly Lee (who had never acted before). When filming began, they were 8 and 13 years old. Yang made amendments to the script accordingly.

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Yi Yi holds an approval rating of 97%, based on 87 critic reviews with an average rating of 8.3/10. The site's consensus reads: "In its depiction of one family, Yi Yi accurately and expertly captures the themes and details, as well as the beauty, of everyday life".[5] On Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, the film holds a score of 94 out of 100, based on 25 critic reviews.[6]

In his review of the film for The New York Times, A. O. Scott revealed: "As I watched the final credits of Yi Yi through bleary eyes, I struggled to identify the overpowering feeling that was making me tear up. Was it grief? Joy? Mirth? Yes, I decided, it was all of these. But mostly, it was gratitude".[7] Kenneth Turan wrote in the Los Angeles Times: "It's a delicate film but a strong one, graced with the ability to see life whole, the grief hidden in happiness as well as the humor inherent in sadness".[8] J. Hoberman of The Village Voice called Yi Yi a "lucid, elegant, nuanced, humorous melodrama that's never nearly as sentimental as it might have been" and praised Yang's direction, which he remarked "orchestrates a soap opera season's worth of family crises with virtuoso discretion".[9] The New Yorker critic David Denby concluded: "By degrees, with incredible calm and patience, the narrative takes hold, and by the end nearly every shot seems momentous".[10]

Accolades

[edit]After debuting at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival, Yi Yi collected a host of awards from international festivals. It garnered director Edward Yang Best Director at Cannes and was nominated for the Palme d'Or in the same year. Yi Yi also won the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival's Netpac Award ("For the perceptive and sensitive portrayal of a generation and cultural gap in Taiwan and the painful choices to be made in these difficult times") and the Vancouver International Film Festival's Chief Dan George Humanitarian Award. It tied with Topsy-Turvy for the 2000 Sarajevo Film Festival's Panorama Jury Award.

It won Best Foreign Film from the French Syndicate of Cinema Critics in 2001, the Grand Prix at the Fribourg International Film Festival in Switzerland in 2001, The Best Foreign Film from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards in 2000, Best Film from the National Society of Film Critics in 2001 (where Yang also won 2nd place for a Best Director Award), and Best Foreign Language Film from the New York Film Critics Circle Awards in 2000. The film was nominated for the prestigious Grand Prix of the Belgian Syndicate of Cinema Critics. The film also won a "Best Film – China/Taiwan" award and "Best Director" award from the 2002 Chinese Film Media Awards, a "Best Film" award at the 2001 Chinese Film Media Awards. It was named one of the best movies of 2001 by many prominent publications and critics, including The New York Times, Newsweek, USA Today, the Village Voice, Film Comment, the Chicago Reader, and the author Susan Sontag, among others. Specifically, Yi Yi was named "Best Film of the Year" (2000) by the following film critics and writers: A. O. Scott of The New York Times, Susan Sontag writing for Artforum, Michael Atkinson of the Village Voice, Steven Rosen of The Denver Post, John Anderson, Jan Stuart and Gene Seymour writing for Newsday, and Stephen Garrett as well as Nicole Keeter of Time Out New York.

The film also won 2nd place for Best Director, Best Film and Best Foreign Language Film in the 2000 Boston Society of Film Critics Awards, and was also nominated for: a Best Foreign Language Film award from the Awards Circuit Community Awards, a Best Non-American Film award from the 2003 Bodil Awards, a Best Foreign Language Film award from the 2001 Chicago Film Critics Association Awards, the Best Cast, a Best Foreign Film award from the 2001 Cesar Awards, a Screen International Award from the 2000 European Film Awards, a Best Asian Film award from the 2002 Hong Kong Film Awards, a Best Foreign Language Film award from the Online Film & Television Association, a Best Foreign Language Film award from the 2001 Online Film Critics Society Awards, and a Golden Spike award from the 2000 Valladolid International Film Festival.

In 2002, the British film magazine Sight & Sound selected Yi Yi as one of the ten greatest films of the past 25 years.

Yi Yi also placed third in a 2009 Village Voice Film Poll ranking "The Best Film of the Decade", tying with La Commune (Paris, 1871) (2000) and Zodiac (2007), and also placed third in a 2009 IndieWire Critics' Poll of the "Best Film of the Decade". The film was summarized by film critic Nigel Andrews, who wrote in the Financial Times that to "describe [Yi Yi] as a three-hour Taiwanese family drama is like calling Citizen Kane a film about a newspaper."[11]

Aggregation site They Shoot Pictures, Don't They has named it as the third most acclaimed film of the 21st century among critics.[2] It also received 20 total votes in the 2012 Sight & Sound polls,[12] and was ranked the eighth-greatest film of the 21st century in a 2016 BBC poll.[3] In 2019, The Guardian ranked Yi Yi 26th in its 100 Best Films of the 21st Century list.[13]

Home media

[edit]The film is available on The Criterion Collection and features a newly restored digital transfer along with a DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack (on the Blu-ray), audio commentary from Yang and Asian film critic Tony Rayns.[14]

Soundtrack

[edit]The piano pieces in Yi Yi's soundtrack are mostly performed by Kaili Peng, Yang's wife. They include Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata and J. S. Bach's Toccata in E minor (BWV 914). Peng has a small cameo in the film as a concert cellist, playing Beethoven's Cello sonata No. 1 with her husband posing as a pianist.

References

[edit]- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Yi Yi: A One and a Two". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "21st Century (Full List)". They Shoot Pictures, Don't They. 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott (June 9, 2017). "The 25 Best Films of the 21st Century". NY Times. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ "A One and a Two... - Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Yi Yi, retrieved April 20, 2023

- ^ Kehr, Dave (January 14, 2001). "FILM; In Theaters Now: The Asian Alternative". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (December 1, 2000). "A Delicate, Confident Look at the Wonder of Humanity". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (October 3, 2000). "It's All Relative". The Village Voice. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Denby, David (December 31, 2000). "Revolutions". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ John Anderson, Edward Yang, University of Illinois Press, page 10 (2005).

- ^ "Votes for A One and a Two". British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter; Clarke, Cath; Pulver, Andrew; Shoard, Catherine (September 13, 2019). "The 100 best films of the 21st century". The Guardian. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Yi Yi". The Criterion Collection.

External links

[edit]- Yi Yi at IMDb

- Yi Yi at AllMovie

- Yi Yi at Metacritic

- Yi Yi at Rotten Tomatoes

- Yi Yi at Box Office Mojo

- Yi Yi: Time and Space an essay by Kent Jones at the Criterion Collection

- 2000 films

- 2000 drama films

- 2000 independent films

- 2000s English-language films

- English-language Taiwanese films

- English-language Japanese films

- Films directed by Edward Yang

- 2000s Mandarin-language films

- Taiwanese drama films

- Taiwanese-language films

- Films set in Taiwan

- Films shot in Taiwan

- Films set in Tokyo

- Films shot in Tokyo

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film winners

- English-language independent films