Russian Ark

| Russian Ark | |

|---|---|

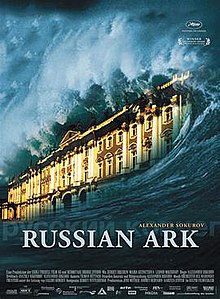

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alexander Sokurov |

| Written by | Anatoli Nikiforov Alexander Sokurov |

| Produced by | Andrey Deryabin Jens Meurer Karsten Stöter |

| Starring |

|

| Narrated by | Alexander Sokurov |

| Cinematography | Tilman Büttner |

| Edited by | Stefan Ciupek Sergei Ivanov Betina Kuntzsch Patrick Wilfert |

| Music by | Sergei Yevtushenko |

Production company | Seville Pictures |

| Distributed by | Wellspring Media |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | ~$2.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $8.7 million[2] |

Russian Ark (Russian: Русский ковчег, romanized: Russkij kovcheg) is a 2002 experimental historical drama film directed by Alexander Sokurov. The plot follows an unnamed narrator, who wanders through the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, and implies that he died in some horrible accident and is a ghost drifting through. In each room, he encounters various real and fictional people from various periods in the city's 300-year history. He is accompanied by "the European", who represents the Marquis de Custine, a 19th-century French traveler.[3]

An international co-production between Russia and Germany, Russian Ark was shot entirely in the Winter Palace of the Russian State Hermitage Museum on 23 December 2001, using a one-take single 87-minute Steadicam sequence shot. It extensively uses the fourth wall device, but repeatedly broken and re-erected. At times, the narrator and the companion interact with the other performers, while at other times they pass unnoticed.

The film was entered into the 2002 Cannes Film Festival.[4] Russian Ark is widely regarded as one of the greatest Russian films of all time.[5]

Plot

[edit]On a winter's day, a small party of men and women arrive by horse-drawn carriage to a minor side entrance of the Winter Palace, dressed in the style of the early 19th century to attend a ball hosted by the Emperor Alexander I. The narrator (whose point of view is always in first-person) meets another spectral but visible outsider, "the European", and follows him through numerous rooms of the palace. "The European", a 19th-century French diplomat who appears to be the Marquis de Custine, has nothing but contempt for Russians; he tells the narrator that they are unable to create or appreciate beauty as "Europeans" do, as demonstrated by the European treasures around him. Each room manifests a different period of Russian history, although the periods are not in chronological order.

Featured are Peter the Great harassing and striking one of his generals; a spectacular presentation of operas and plays in the era of Catherine the Great; an imperial audience in which Tsar Nicholas I is offered a formal apology by the Shah of Persia, represented by his grandson Khosrow Mirza, for the death of ambassador Alexander Griboyedov in 1829; the idyllic family life of Tsar Nicholas II's children; the ceremonial changing of the various regiments of the Imperial Guard; contemporary tourists visiting the palace; the museum's director whispering the need to make repairs during the rule of Joseph Stalin; and a desperate Leningrader making his own coffin during the 900-day siege of the city during World War II.

A grand ball follows, held in the Nicholas Hall, with many of the participants in spectacular period costume and a full orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev featuring music by Mikhail Glinka, then a long final exit with a crowd down the grand staircase. The European tells the narrator that he belongs here, in the world of 1913 where everything is still beautiful and elegant, and does not want to go any further. The narrator then walks backwards out the hallway and sees many people from different time periods exiting the building together. As he watches them, the narrator quietly departs the procession, leaves the building through a side door and looks out upon the River Neva.

Cast

[edit]- Alexander Sokurov as Narrator

- Sergei Dontsov (Sergey Dreyden) as the European (Marquis de Custine)

- Mariya Kuznetsova as Catherine the Great

- Maksim Sergeyev as Peter the Great

- Anna Aleksakhina as Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse)

- Vladimir Baranov as Nicholas II

- Svetlana Svirko as Alexandra Feodorovna (Charlotte of Prussia)

Production

[edit]The film displays 33 rooms of the museum, which are filled with a cast of over 2,000 actors and three orchestras. Russian Ark was recorded in uncompressed high-definition video using a Sony HDW-F900 camera. The information was not recorded compressed to tape as usual, but uncompressed onto a hard disk which could hold 100 minutes which was carried behind the cameraman as he traveled from room to room, scene to scene. According to In One Breath: Alexander Sokurov's Russian Ark, the documentary on the making of the film, four attempts were made. The first failed at the five-minute mark. After two more failed attempts, they were left with only enough battery power for one final take. The four hours of daylight available were also nearly gone. Fortunately, the final take was a success and the film was completed at 90 minutes. Tilman Büttner, the director of photography and Steadicam operator, executed the shot on 23 December 2001.

In a 2002 interview, Büttner said that film sound was recorded separately. "Every time I did the take, or someone else made a mistake, I would curse, and that would have gotten in, so we did the sound later."[6] Lighting directors of photography on the film were Bernd Fischer and Anatoli Radionov.[7] The director later rejected Büttner's nomination for a European Film Academy award, believing that only the whole film should gain an award.[8]

Post-production

[edit]In post-production the uncompressed HD 87-minute one-shot could be reworked in detail: besides many object removals (mainly cables and other film equipment), compositings (e.g. additional snow or fog), stabilisations, selective colour-corrections and digitally added focus changes, the whole film was continuously and dynamically reframed (resized) and for certain moments even time-warped (slowed down and sped up). This work took several weeks and was mainly executed by editor Patrick Wilfert under supervision of lead editor Sergei Ivanov on Discreet Logic's Inferno system. Avoiding any playouts and using framestore to framestore transfers only, the picture was left uncompressed, before being reprinted onto filmstock for theatrical distribution.

Background

[edit]The narrator's guide, "the European", is based on the book by the French aristocrat Marquis de Custine, who visited Russia in 1839 and wrote La Russie en 1839, in which he depicted Russia in extremely unflattering terms. A few biographical elements from Custine's life are shown in the film. Like the European, the Marquis' mother was friends with the Italian sculptor Canova and he himself was very religious. Custine's book mocks Russian civilization as a thin veneer of Europe on an Asiatic soul. For Custine, Europe was "civilization" while Asia was "barbarism", and his placing of Russia as a part of Asia rather than Europe was meant to deny that Russians had any sort of civilization worthy of the name. Echoing this sentiment, the film's European comments that Russia is a theater and that the people he meets are actors. The Marquis's family fortune came from a porcelain works, hence the European's interest in the Sèvres porcelain waiting for the diplomatic reception. At the end of the film, which depicts the last imperial ball in 1913, the European appears to accept Russia as a European nation.

In One Breath, a documentary about the making of Russian Ark, written and directed by Knut Elstermann, gives more insight into the single long shot tracking techniques and formidable organization behind the making of the film.[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was not a huge commercial success, though as an arthouse film it performed strongly in many territories. These include the UK, Japan, Korea, Argentina, and especially the US, where the film remains one of the most successful of both German and Russian movies of recent decades.[citation needed]

Russian Ark is a German-Russian co-production. The film grossed $3,048,997 in the United States and Canada, with $5,641,171 internationally, for a worldwide total of $8,690,168.[2]

Critical response

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2016) |

Russian Ark received high critical acclaim. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 89% of critics gave the film a positive review based on 109 reviews, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The consensus review summary reads, "As successful as it is ambitious, Russian Ark condenses three centuries of Russian history into a single, uninterrupted, 87-minute take."[9] On Metacritic, which uses an average of critics' reviews, the film has an 86/100 rating based on 32 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[10]

Roger Ebert wrote, "Apart from anything else, this is one of the best-sustained ideas I have ever seen on the screen.... [T]he effect of the unbroken flow of images (experimented with in the past by directors like Hitchcock and Max Ophüls) is uncanny. If cinema is sometimes dreamlike, then every edit is an awakening. Russian Ark spins a daydream made of centuries."[11]

Slant Magazine ranked the film 84th in its list of the best films of the 2000s.[12] In a critics' and readers' poll by Empire magazine, it was voted the 358th greatest film of all time.[13]

Awards and nominations

[edit]Russian Ark received the Visions Award at the 2002 Toronto International Film Festival, a Special Citation at the 2003 San Francisco Film Critics Circle Awards and the 2004 Silver Condor Award for Best Foreign Film from the Argentine Film Critics Association; it was also nominated for the Palme d'Or at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival, the Golden Hugo at the 2002 Chicago International Film Festival and the 2004 Nika Award for Best Film. In addition, Alexander Sokurov was named Best Director at Fancine in 2003 and was nominated for the 2002 European Film Award for Best Director. Cinematographer Tilman Büttner was also nominated for various awards for his work on the film, including a European Film Award for Best Cinematographer and a German Camera Award.

References

[edit]- ^ "Что такое "Русский ковчег"". Коммерсантъ (in Russian). Kommersant. 25 December 2001. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ a b Russian Ark at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman / Littlefield. pp. 593–594. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Russian Ark". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Vasileva, Mirella (17 February 2018). "The 10 Best Russian Movies of All Time". Taste of Cinema - Movie Reviews and Classic Movie Lists. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Interview: Achieving the Cinematic Impossible". indieWIRE. 26 November 2002. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Full Cast and Crew for Russiky kovcheg". Russiky kovcheg. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "To the European Film Awards". The Island of Sokurov. Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "Russian Ark (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Russian Ark Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "Russian Ark". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "Best of the Aughts: Film". Slant Magazine. 7 February 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Empire Features". www.empireonline.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011.

External links

[edit]- 2002 films

- 2000s avant-garde and experimental films

- 2002 fantasy films

- 2000s historical films

- 2002 drama films

- 2000s ghost films

- Films set in 1829

- Films set in 1913

- Cultural depictions of Catherine the Great

- Cultural depictions of Nicholas II of Russia

- Cultural depictions of Peter the Great

- Cultural depictions of Nicholas I of Russia

- Films directed by Alexander Sokurov

- Films set in art museums and galleries

- Films set in Saint Petersburg

- Films set in the Russian Empire

- Films shot from the first-person perspective

- German historical drama films

- Historical fantasy films

- One-shot films

- 2000s Persian-language films

- Russian detective films

- Russian fantasy drama films

- Russian historical drama films

- 2000s Russian-language films

- Canadian historical drama films

- Finnish historical drama films

- German mystery drama films

- Canadian mystery drama films

- 2002 multilingual films

- German multilingual films

- Russian multilingual films

- Canadian multilingual films

- Finnish multilingual films

- 2000s Canadian films

- 2000s German films

- Russian-language Canadian films