Tristan chord

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| augmented second | |

| augmented sixth | |

| augmented fourth (tritone) | |

| root [F] | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 4–27 / |

The original Tristan chord is heard in the opening phrase of Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde as part of the leitmotif relating to Tristan. It is made up of the notes F, B, D♯, and G♯:

More generally, the term refers to any chord that consists of the same intervals: augmented fourth, augmented sixth, and augmented ninth above a bass note.

Background

[edit]The notes of the Tristan chord are not unusual; they could be respelled enharmonically to form a common half-diminished seventh chord. What distinguishes the Tristan chord is its unusual relationship to the implied key of its surroundings.

This motif also appears in measures 6, 10, and 12, several times later in the work,[clarification needed] and at the end of the last act.

Martin Vogel points out the "chord" in earlier works by Guillaume de Machaut, Carlo Gesualdo, J. S. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, or Louis Spohr[1] as in the following example from the first movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 18:

The chord is found in several works by Chopin, from as early as 1828, in the Sonata in C minor, Op. 4 and his Scherzo No. 1, composed in 1830.[2] It is only in late works where tonal ambiguities similar to Wagner's arise, as in the Prelude in A minor, Op. 28, No. 2, and the posthumously published Mazurka in F minor, Op. 68, No. 4.[3]

The Tristan chord's significance is in its move away from traditional tonal harmony, and even toward atonality. With this chord, Wagner actually provoked the sound or structure of musical harmony to become more predominant than its function, a notion that was soon explored by Debussy and others. In the words of Robert Erickson, "The Tristan chord is, among other things, an identifiable sound, an entity beyond its functional qualities in a tonal organization".[4]

Analysis

[edit]Much has been written about the Tristan chord's possible harmonic functions or voice leading and the motif has been interpreted in various ways. Though enharmonically equivalent to the half-diminished seventh chord Fø7 (F–A♭–C♭–E♭), the Tristan chord can also be interpreted in many ways. Nattiez distinguishes between functional and nonfunctional analyses of the chord.[5]

Functional analyses

[edit]Functional analyses have interpreted the chord in the key of A minor in many ways:

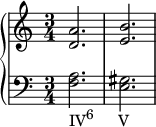

- The chord is an augmented sixth chord, specifically a French sixth chord, F–B–D♯-A, with the note G♯ heard as an appoggiatura resolving to A. (Theorists debate the root of French sixth chords.) The harmonic function as a predominant is intact, with the chord moving to V7. Note that, in this view, the G# resolving upward to A is the 2nd of 3 consecutive accented dissonances resolving by half step. Alfred Lorenz and others interpret it more broadly as an augmented sixth chord F–A–D♯,[7][8][9][10] based after Hugo Riemann on the principle that there are only three chord functions: tonic, predominant, and dominant.

- The root is the second scale degree, B.[11][12][13][14]

- The root is the fourth scale degree, D. Arend interprets it as "a modified minor seventh chord"[15]

- F–B–D♯–G♯ → F–C♭–E♭–A♭ → F–B–D–A = D–F–A

- The chord is a secondary dominant, V/V, and thus also with a root on B.[16][17][18] This favors the fifth motion from B to E, seeing the chord as a seventh chord with lowered fifth (B–D♯(D♮)–F♯–A).

Vincent d'Indy[19] analyses the chord as a IV chord after Riemann's transcendent principle (as phrased by Serge Gut:[20] "the most classic succession in the world: Tonic, Predominant, Dominant" ) and rejects the idea of an added "lowered seventh", eliminates "all artificial, dissonant notes, arising solely from the melodic motion of the voices, and therefore foreign to the chord," finding that the Tristan chord is "no more than a predominant in the key of A, collapsed in upon itself melodically, the harmonic progression represented thus:

Célestin Deliège, independently, sees the G♯ as an appoggiatura to A, describing that

in the end only one resolution is acceptable, one that takes the subdominant degree as the root of the chord, which gives us, as far as tonal logic is concerned, the most plausible interpretation ... this interpretation of the chord is confirmed by its subsequent appearances in the Prelude's first period: the IV6 chord remains constant; notes foreign to that chord vary.[21]

According to Jacques,[22] discussing Dommel-Diény[23] and Gut,[24] "it is rooted in a simple dominant chord of A minor [E major], which includes two appoggiaturas resolved in the normal way". Thus, in this view it is not a chord but an anticipation of the dominant chord in measure three. Chailley did once write:

Tristan's chromaticism, grounded in appoggiaturas and passing notes, technically and spiritually represents an apogee of tension. I have never been able to understand how the preposterous idea that Tristan could be made the prototype of an atonality grounded in destruction of all tension could possibly have gained credence. This was an idea that was disseminated under the (hardly disinterested) authority of Schoenberg, to the point where Alban Berg could cite the Tristan Chord in the Lyric Suite, as a kind of homage to a precursor of atonality. This curious conception could not have been made except as the consequence of a destruction of normal analytical reflexes leading to an artificial isolation of an aggregate in part made up of foreign notes, and to consider it—an abstraction out of context—as an organic whole. After this, it becomes easy to convince naive readers that such an aggregation escapes classification in terms of harmony textbooks.[25]

Fred Lerdahl presents alternate interpretations of the Tristan motive, as either i ii♯643 [French sixth: F–B–D♯–A] V7 or as VI (iv) (vii♯64♯2) [ altered pre-dominant: F–B–D♯–G♯] V7, both in A minor, concluding that while both interpretations have strong expectation or attraction, that the version with G♯ is the stronger progression.[26]

Nonfunctional analyses

[edit]Nonfunctional analyses are based on structure (rather than function), and are characterized as vertical characterizations or linear analyses.

Vertical characterizations include interpreting the chord's root as on the seventh degree (VII),[27][28] of F♯ minor.[29][30]

Linear analyses include that of Noske[31] and Schenker was the first to analyze the motif entirely through melodic concerns. Schenker and later Mitchell compare the Tristan chord to a dissonant contrapuntal gesture from the E minor fugue of The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I.[32]

William Mitchell, viewing the Tristan chord from a Schenkerian perspective, does not see the G♯ as an appoggiatura because the melodic line (G♯–A–A♯–B) ascends to B, making the A a passing note. This ascent by minor third is mirrored by the descending line (F–E–D♯–D), a descent by minor third, making the D♯, like A♯, an appoggiatura. This makes the chord a diminished seventh chord (G♯–B–D–F).

Serge Gut argues that, "if one focuses essentially on melodic motion, one sees how its dynamic force creates a sense of an appoggiatura each time, that is, at the beginning of each measure, creating a mood both feverish and tense ... thus in the soprano motif, the G♯ and the A♯ are heard as appoggiaturas, as the F and D♯ in the initial motif."[20] The chord is thus a minor chord with an added sixth (D–F–A–B) on the fourth degree (IV), though it is engendered by melodic waves.

Allen first identifies the chord as an atonal set, 4–27 (half-diminished seventh chord), then "elect[s] to place that consideration in a secondary, even tertiary position compared to the most dynamic aspect of the opening music, which is clearly the large-scale ascending motion that develops in the upper voice, in its entirety a linear projection of the Tristan Chord transposed to level three, g♯′–b′–d″–f♯″.[33]

Schoenberg describes it as a "wandering chord [vagierender Akkord]... it can come from anywhere".[34]

Mayrberger's opinion

[edit]After summarizing the above analyses Nattiez asserts that the context of the Tristan chord is A minor, and that analyses which say the key is E major or E♭ minor are "wrong".[35] He privileges analyses of the chord as on the second degree (II). He then supplies a Wagner-approved analysis, that of Czech professor Carl Mayrberger[36] who "places the chord on the second degree, and interprets the G♯ as an appoggiatura. But above all, Mayrberger considers the attraction between the E and the real bass F to be paramount, and calls the Tristan chord a Zwitterakkord (an ambiguous, hybrid, or possibly bisexual or androgynous, chord), whose F is controlled by the key of A minor, and D♯ by the key of E minor".[37]

Responses and influences

[edit]![{

#(set-global-staff-size 17)

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\key ges \major \time 2/4

\partial 4.

\new Voice \relative c' {

\once \hide Score.MetronomeMark \once \hide Score.MetronomeMark\tempo 4 = 80 r8 \voiceOne a4( \tempo "Cédez" f'4.^\markup { \dynamic p \italic "avec une grande émotion" } e8)

\tempo "a Tempo" r8 \once \hide Score.MetronomeMark \tempo 4 = 105 \acciaccatura{\slurUp d'} \once \stemDown <ces es>8-.[ \acciaccatura{\slurUp c} \once \stemDown <ces des>-. \acciaccatura{\slurUp d} \once \stemDown <ces es>-.]

r8 \acciaccatura{\slurUp d} \once \stemDown <ces es>8-.[ \acciaccatura{\slurUp c} \once \stemDown <ces des>-. \acciaccatura{\slurUp d} \once \stemDown <ces es>-.]

}

\new Voice \relative c' {

\voiceTwo s8 a4(~ a4. bes8 <ces es!>2)

}

>>

\new Staff <<

\clef bass

\key ges \major \time 2/4

\partial 4.

\new Voice \relative c, {

<< {

\voiceOne r8 r4 r2

r8 \stemDown <as'' ces f>-.[ <as ces f>8-. <as ces f>8-.]

}

\new Voice \relative c {

\voiceTwo es,8([ f ges]

a[ bes ces c]

<as des>2)} >>

r8 <as ces f>8-.[ <as ces f>8-. <as ces f>8-.]

}

>>

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/d/ldmsdstu2yi2v2i6unwf0my1c53o685/ldmsdstu.png)

The chord and the figure surrounding it is well enough known to have been parodied and quoted by a number of later musicians. Debussy includes the chord in a setting of the phrase je suis triste in his opera Pelléas et Mélisande.[38] Debussy also jokingly quotes the opening bars of Wagner's opera several times in "Golliwogg's Cakewalk" from his piano suite Children's Corner.[39] Benjamin Britten slyly invokes it at the moment in Albert Herring when Sid and Nancy spike Albert's lemonade and then, when he drinks it, the chord "runs riot through the orchestra and recurs irreverently to accompany his hiccups".[40] Paul Lansky based the harmonic content of his first electronic piece, mild und leise (1973), on the Tristan chord.[41] This piece is best known from being sampled in the Radiohead song "Idioteque".

Bernard Herrmann incorporated the chord in his scores for Vertigo (1958) and Tender is the Night (1962).[citation needed]

Christian Thielemann, the music director of the Bayreuth Festival from 2015–20, discussed the Tristan chord in his book, My Life with Wagner: the chord "is the password, the cipher for all modern music. It is a chord that does not conform to any key, a chord on the verge of dissonance", and "The Tristan chord does not seek to be resolved in the closest consonance, as the classic theory of harmony requires; [it] is sufficient unto itself, just as Tristan and Isolde are sufficient unto themselves and know only their love."[42]

More recently, American composer and humorist Peter Schickele crafted a tango around the Tristan prelude, a chamber work for four bassoons entitled Last Tango in Bayreuth.[43] The Brazilian conductor and composer Flavio Chamis wrote Tristan Blues, a composition based on the Tristan chord. The work, for harmonica and piano was recorded on the CD Especiaria, released in Brazil by the Biscoito Fino label.[44] Additionally, New York-based composer Dalit Warshaw's narrative concerto for piano and orchestra, Conjuring Tristan, employs the Tristan chord in exploring the themes of Thomas Mann's novella Tristan through Wagner's music.[45]

The prelude of Wagner's opera is prominently used in the film Melancholia by Lars von Trier.[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Vogel 1962, p. 12, cited in Nattiez 1990, p. 219

- ^ Walker 2018, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Gołąb 1987, [page needed].

- ^ Erickson 1975, p. 18.

- ^ Nattiez 1990, pp. 219–229.

- ^ Benward and Saker 2008, p. 233.

- ^ D'Indy 1903, [page needed].

- ^ Lorenz 1924–33, [page needed].

- ^ Deliège 1979, [page needed].

- ^ Gut 1981, [page needed].

- ^ Piston 1987, p. 426.

- ^ Goldman 1965, [page needed].

- ^ Schoenberg 1954, [page needed].

- ^ Schoenberg 1969, p. 77.

- ^ Arend 1901, [page needed].

- ^ Ergo 1912, [page needed].

- ^ Kurth 1920, [page needed].

- ^ Distler 1940, [page needed].

- ^ D'Indy 1903, p. 117, cited in Nattiez 1990, p. 224

- ^ a b Gut 1981, p. 150.

- ^ Deliège 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Chailley 1963, p. 40.

- ^ Dommel-Diény 1965.

- ^ Gut 1981, p. 149, cited in Nattiez (1990, p. 220)

- ^ Chailley 1963, p. 8.

- ^ Lerdahl 2001, p. 184.

- ^ Ward 1970.

- ^ Sadai 1980.

- ^ Kistler 1879, [page needed].

- ^ Jadassohn 1899, [page needed].

- ^ Noske 1981, pp. 116–117.

- ^ cf. Schenker 1925–30, 2: p. 29

- ^ Forte 1988, p. 328.

- ^ Schoenberg 1911, p. 284.

- ^ Nattiez 1990, p. 233.

- ^ Mayrberger 1878, [page needed].

- ^ Nattiez 1990, p. 235-236.

- ^ Huebner 1999, p. 477.

- ^ Groos 2011, p. 163.

- ^ Howard 1969, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Grimshaw.

- ^ Thielemann, Christian (2016). My life with Wagner : fairies, rings, and redemption : exploring opera's most enigmatic composer. New York: Pegasus Books. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-1-68177-125-0. OCLC 923794429.

- ^ Ross, Alex (2013-05-19). "A Wagner Birthday Roast". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ Anon. 2006.

- ^ Kaczmarczyk, Jeffrey (2015-01-31). "Many lovely moments in Grand Rapids Symphony's evening of music by Wagner". mlive. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ Page 2011.

Sources

[edit]- Anon. 2006. "Especiaria CD: Flávio Chamis". Biscoito Fino website (archive from 24 August 2011, accessed 16 May 2014).

- Arend, M. (1901). "Harmonische Analyse des Tristan-Vorspiels", Bayreuther Blätter. No. 24: 160–169. Cited in Nattiez 1990, p. 223.

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2008). Music in Theory and Practice, vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- Chailley, Jacques (1963). Tristan et Isolde de Richard Wagner. 2 vols. Les Cours de Sorbonne. Paris: Centre de Documentation Universitaire.

- Deliège, Célestin (1979)[full citation needed]

- D'Indy, Vincent (1903). Cours de composition musicale, vol. 1. Paris: Durand.

- Distler, Hugo (1940). Funktionelle Harmonielehre. Basel: Bärenreiter-Verlag.

- Dommel-Diény, Amy. 1965. Douze dialogues d'initiation à l'harmonie classique; suivis de quelques notions de solfège, preface by Louis Martin. Paris: Les Editions Ouvrières.

- Ergo, E. (1912). "Über Wagners Harmonik und Melodik". Bayreuther Blätter, no. 35:34–41.

- Erickson, Robert (1975). Sound Structure in Music. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02376-5.

- Forte, Allen (1988). New Approaches to the Linear Analysis of Music. Journal of the American Musicological Society 41, no. 2 (Summer): 315–348.

- Gołąb, Maciej. 1987. "O 'akordzie tristanowskim' u Chopina". Rocznik Chopinowski 19:189–98. German version, as "Über den Tristan-Akkord bei Chopin". Chopin Studies 3 (1990): 246–256. English version, as "On the Tristan Chord", in: M. Gołąb, Twelve Studies in Chopin, Frankfurt am Main 2014: 81-92

- Goldman, Richard Franko (1965). Harmony in Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Grimshaw, Jeremy. "mild und leise, computer synthesized tape". AllMusic. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- Groos, Arthur, ed. (2011). Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521431385. OCLC 660804858.

- Gut, Serge (1981). "Encore et toujours: 'L'accord de Tristan'", L'avant-scène Opéra, nos. 34–35 ("Tristan et Isole"): 148–151.

- Howard, Patricia (1969), The Operas of Benjamin Britten: An Introduction, New York and Washington: Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers

- Huebner, Steven (1999). French Opera at the Fin de Siècle: Wagnerism, Nationalism, and Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195189544. OCLC 40043694.

- Jadassohn, Josef. 1899. L'organisation actuelle de la surveillance médicale de la prostitution est-elle susceptible d'amélioration? Brussels: [s.n.].

- Kistler, Cyrill (1879), Harmonielehre für Lehrer und Lernende, Opus 44, Munich: W. Schmid.

- Kurth, Ernst. 1920. Romantische Harmonik und ihre Krise in Wagners "Tristan". Bern: Paul Haupt; Berlin: Max Hesses Verlag.

- Lerdahl, Fred (2001). Tonal Pitch Space. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517829-7.

- Lorenz, Alfred Ottokar. 1924–33. Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner, in 4 volumes. Berlin: M. Hesse. Reprinted, Tutzing: H. Schneider, 1966.

- Mayrberger, Carl. 1878. Lehrbuch der musikalischen Harmonik in gemeinfasslicher Darstellung, für höhere Musikschulen und Lehrerseminarien, sowie zum Selbstunterrichte. Part 1: "Die diatonische Harmonik in Dur". Pressburg: Gustav Heckenast.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990) [1987]. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music (Musicologie générale et sémiologue). Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02714-5.

- Noske, Frits R. (1981). "Melodic Determinants in Tonal Structures". Muzikoloski zbornik Ljubljana / Ljubljana Musicological Annual 17, no. 1:111–121.

- Page, Tim (23 December 2011). "Filmmaker's Audacious Teaming of His 'Melancholia' with Wagner's Music". The Washington Post.

- Piston, Walter (1987). Harmony. Revised by Mark Devoto (5th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95480-7.

- Sadai, Yizhak (1980). Harmony in Its Systemic and Phenomenological Aspects, translated by J. Davis and M. Shlesinger. Jerusalem: Yanetz.

- Schenker, Heinrich (1925–30). Das Meisterwerk in der Musik, 3 vols. Munich: Drei Masken Verlag. English translation, as The Masterwork in Music: A Yearbook, edited by William Drabkin, translated by Ian Bent, Alfred Clayton, William Drabkin, Richard Kramer, Derrick Puffett, John Rothgeb, and Hedi Siegel. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 4. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994–1997.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1911). Harmonielehre. Leipzig and Vienna: Verlagseigentum der Universal-Edition.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1954). Die formbildenden Tendenzen der Harmonie, translated by Erwin Stein. Mainz: B. Schott's Sohne.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1969). "Structural Functions of Harmony", revised edition. New York: W. W. Norton. Library of Congress – 74-81181.

- Vogel, Martin (1962). Der Tristan-Akkord und die Krise der modernen Harmonielehre. Orpheus-Schriftenreihe zu Grundfragen der Musik 2. Düsseldorf:[full citation needed] Titled in response to Kurth (1920).

- Walker, Alan (2018). Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times. Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571348572.

- Ward, William R. (1970). Examples for the Study of Musical Style. Dubuque: W. C. Brown Co. ISBN 9780697035417.

Further reading

[edit]- Bailey, Robert (1986). Prelude and Transfiguration from Tristan and Isolde (Norton Critical Scores). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-95405-6. Contains complete orchestral score, together with extensive discussion of the Prelude (especially the chord), Wagner's sketches, and leading essays by various analysts.

- Ellis, Mark (2010). A Chord in Time: The Evolution of the Augmented Sixth from Monteverdi to Mahler. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6385-0.

- Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899a. Erläuterungen der in Joh. Seb. Bach's Kunst der Fuge enthaltenen Fugen und Kanons. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. English as, An Analysis of the Fugues and Canons Contained in Joh. Seb. Bach's "Art of fugue". Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1899.

- Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899b. A Manual of Harmony. New York: G. Schirmer.

- Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899c. Ratschläge und Hinweise für die Instrumentationsstudien der Anfänger. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899d. Das Wesen der Melodie in der Tonkunst. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Das Tonbewusstsein: die Lehre vom musikalischen Hören. English as, A Practical Course in Ear Training; or, a Guide for Acquiring Relative and Absolute Pitch, translated from the German by Le Roy B. Campbell. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1899.

- Jadassohn, Salomon. 1899e. Zur Einführung in J.S. Bach's Passions-Musik nach dem Evangelisten Matthaeus. Berlin: Harmonie.

- Magee, Bryan (2002). The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy. Macmillan. ISBN 0-8050-7189-X.

- Mayrberger, Carl. 1994 [1881]. "Die Harmonik Richard Wagner’s an den Leitmotiven aus Tristan und Isolde (1881)", translated and annotated by Ian Bent. In Music Analysis in the Nineteenth Century, Volume 1: Fugue, Form and Style, edited by Ian Bent, 221–252. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-25969-9.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990b), Wagner androgyne, C. Bourgois, ISBN 2-267-00707-X Contains discussion of the Tristan chord as "androgynous". 1997 English edition (translated by Stewart Spencer) ISBN 0-691-04832-0.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1872. "Über Tonalität". Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 68: 443–445, 451–454.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1875. Die Hülfsmittel der Modulation: Studie von Dr. Hugo Riemann. Kassel: F. Luckhardt.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1877. Musikalische Syntaxis: Grundriss einer harmonischen Satzbildungslehre, revised edition. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1882. "Die Natur der Harmonik". In Sammlung musikalischer Vorträge 40, revised edition, edited by P. Graf Waldersee, 4:157–190. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. English translation, as "The Nature of Harmony", by John Comfort Fillmore, in his New Lessons in Harmony, 3–32. Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1887.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1883a. Elementar-Musiklehre. Hamburg: K. Grädener & J. F. Richter.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1883b. Neue Schule der Melodik: Entwurf einer Lehre des Kontrapunkts nach einer neuen Methode. Hamburg: K. Grädener & J. F. Richter.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1887. Systematische Modulationslehre als Grundlage der musikalischen Formenlehre. Hamburg: J. F. Richter.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1893. Opern-Handbuch, second edition, with a supplement by F. Stieger. Leipzig: Koch.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1895. Präludien und Studien: gesammelte Aufsätze zur Ästhetik, Theorie und Geschichte der Musik, revised edition, vol. 1. Frankfurt: Bechhold.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1900. Präludien und Studien: gesammelte Aufsätze zur Ästhetik, Theorie und Geschichte der Musik, revised edition, vol. 2. Leipzig: Seemann.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1901a. Präludien und Studien: gesammelte Aufsätze zur Ästhetik, Theorie und Geschichte der Musik, vol. 3. Leipzig: Seemann. Reprint (3 vols. in 1), Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1967. Reprint (3 vols. in 2), Nendeln/Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1976.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1901b. Geschichte der Musik seit Beethoven (1800–1900) . Berlin and Stuttgart: W. Spemann

- Riemann, Hugo. 1903. Vereinfachte Harmonielehre oder die Lehre von den tonalen Funktionen der Akkorde, second edition. London: Augener; New York: G. Schirmer.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1905. "Das Problem des harmonischen Dualismus". Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 101:3–5, 23–26, 43–46, 67–70

- Riemann, Hugo. 1902–13. Grosse Kompositionslehre, revised edition, 3 vols. Berlin and Stuttgart: W. Spemann.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1914–15. "Ideen zu einer 'Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen'", Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 1914–15, 1–26. Reprinted in Musikhören, edited by B. Dopheide, 14–47. Darmstadt: [s.n.?], 1975. English translation by ? in Journal of Music Theory 36 (1992): 69–117.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1916. "Neue Beiträge zu einer Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen". Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 1916: 1–21.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1919. Elementar-Schulbuch der Harmonielehre, third edition. Berlin: Max Hesse.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1921. Geschichte der Musiktheorie im 9.–19. Jahrhundert, revised edition, 3 vols. Berlin: Max Hesse. Reprinted, Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1990. ISBN 9783487002569.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1922. Allgemeine Musiklehre: Handbuch der Musik, 9th edition. Max Hesses Handbücher 5. Berlin: Max Hesse.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1929. Handbuch der Harmonielehre, 10th edition, formerly titled Katechismus der Harmonie- und Modulationslehre and Skizze einer neuen Methode der Harmonielehre. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Schering, Arnold (1935). "Musikalische Symbolkunde". Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek:15–36.

- Stegemann, Benedikt (2013). Theory of Tonality. Theoretical Studies. Wilhelmshaven: Noetzel. ISBN 978-3-7959-0963-5.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1883). Erinnerungen an Richard Wagner: ein Vortrag, gehalten am 13 April 1883 im Wissenschaftlichen Club zu Wien. Vienna: C. Konegen.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1888). Wagneriana. Gesammelte Aufsätze über R. Wagner's Werke, vom Ring bis zum Gral. Eine Gedenkgabe für alte und neue Festspielgäste zum Jahre 1888. Leipzig: F. Freund.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1891). Erinnerungen an Richard Wagner (new ed.). Leipzig: P. Reclam.

- Wolzogen, Hans von, ed. (1904). Wagner-Brevier. Die Musik, Sammlung illustrierter Einzeldarstellungen 3. Berlin: Bard und Marquardt.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1906a). Musikalisch-dramatische Parallelen: Beiträge zur Erkenntnis von der Musik als Ausdruck. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1906b). "Einführung". In Heinrich Porges, Tristan und Isolde, with an introduction by Hans von Wolzogen. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1907). "Einführung". In Richard Wagner, Entwürfe zu: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Tristan und Isolde, Parsifal, edited by Hans von Wolzogen. Leipzig: C. F. W. Siegel.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1908). Aus Richard Wagners Geisteswelt: neue Wagneriana und Verwandtes. Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1924). Wagner und seine Werke, ausgewählte Aufsätze. Deutsche Musikbücherei. Vol. 32. Regensburg: Gustav Bosse Verlag.

- Wolzogen, Hans von (1929). Musik und Theater. Von deutscher Musik. Vol. 37. Regensburg: Gustav Bosse.