Blind Willie McTell

Blind Willie McTell | |

|---|---|

McTell recording for John Lomax in an Atlanta hotel room, November 1940 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | William Samuel McTier |

| Also known as |

|

| Born | May 5, 1898 Thomson, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | August 19, 1959 (aged 61) Milledgeville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1910s–1956 |

| Labels | |

Blind Willie McTell (born William Samuel McTier; May 5, 1898 – August 19, 1959) was an American Piedmont blues and ragtime singer and guitarist. He played with a fluid, syncopated fingerstyle guitar technique, common among many exponents of Piedmont blues. Unlike his contemporaries, he came to use twelve-string guitars exclusively. McTell was also an adept slide guitarist, unusual among ragtime bluesmen. His vocal style, a smooth and often laid-back tenor, differed greatly from the harsher voices of many Delta bluesmen such as Charley Patton. McTell performed in various musical styles, including blues, ragtime, religious music, and hokum.

McTell was born in Thomson, Georgia. He learned to play the guitar in his early teens. He soon became a street performer in several Georgia cities, including Atlanta and Augusta, and first recorded in 1927 for Victor Records. He never produced a major hit record, but he had a prolific recording career with different labels and under different names in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1940, he was recorded by the folklorists John A. Lomax and Ruby Terrill Lomax for the folk song archive of the Library of Congress. He was active in the 1940s and 1950s, playing on the streets of Atlanta, often with his longtime associate Curley Weaver. Twice more he recorded professionally. His last recordings originated during an impromptu session recorded by an Atlanta record store owner in 1956. McTell died three years later, having lived for years with diabetes and alcoholism. Despite his lack of commercial success, he was one of the few blues musicians of his generation who continued to actively play and record during the 1940s and 1950s. He did not live to see the American folk music revival, in which many other bluesmen were "rediscovered".[1]

McTell's influence extended over a wide variety of artists, including the Allman Brothers Band, who covered his "Statesboro Blues", and Bob Dylan, who paid tribute to him in his 1983 song "Blind Willie McTell", the refrain of which is "And I know no one can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell". Other artists influenced by McTell include Taj Mahal, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Ralph McTell, Chris Smither, and both Jack White and the White Stripes.

Biography

[edit]He was born William Samuel McTier[2] in the Happy Valley community outside Thomson, Georgia. Most sources give the date of his birth as 1898, but researchers Bob Eagle and Eric LeBlanc suggest 1903, on the basis of his entry in the 1910 census.[3] McTell was born blind in one eye and lost his remaining vision by late childhood. He attended schools for the blind in Georgia, New York and Michigan and showed proficiency in music from an early age, first playing the harmonica and accordion, learning to read and write music in braille,[1] and turning to the six-string guitar in his early teens.[1][2] His family background was rich in music; both of his parents and an uncle played the guitar. He was related to the bluesman and gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey.[2] McTell's father left the family when Willie was young. After his mother died, in the 1920s, he left his hometown and became an itinerant musician, or "songster". He began his recording career in 1927 for Victor Records in Atlanta.[4]

McTell married Ruth Kate Williams,[1] now better known as Kate McTell, in 1934. She accompanied him on stage and on several recordings before becoming a nurse in 1939. For most of their marriage, from 1942 until his death, they lived apart, she in Fort Gordon, near Augusta, and he working around Atlanta.

In the years before World War II, McTell traveled and performed widely, recording for several labels under different names: Blind Willie McTell (for Victor and Decca), Blind Sammie (for Columbia), Georgia Bill (for Okeh), Hot Shot Willie (for Victor), Blind Willie (for Vocalion and Bluebird), Barrelhouse Sammie (for Atlantic), and Pig & Whistle Red (for Regal).[5] The appellation "Pig & Whistle" was a reference to a chain of barbecue restaurants in Atlanta;[6] McTell often played for tips in the parking lot of a Pig 'n Whistle restaurant. He also played behind a nearby building that later became Ray Lee's Blue Lantern Lounge. Like Lead Belly, another songster who began his career as a street artist, McTell favored the somewhat unwieldy and unusual twelve-string guitar, whose greater volume made it suitable for outdoor playing.

In 1940 John A. Lomax and his wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax, a professor of classics at the University of Texas at Austin, interviewed and recorded McTell for the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress in a two-hour session held in their hotel room in Atlanta.[7] These recordings document McTell's distinctive musical style, which bridges the gap between the raw country blues of the early part of the 20th century and the more conventionally melodious, ragtime-influenced East Coast Piedmont blues sound. The Lomaxes also elicited from the singer traditional songs (such as "The Boll Weevil" and "John Henry") and spirituals (such as "Amazing Grace"),[8] which were not part of his usual commercial repertoire. In the interview, John A. Lomax is heard asking if McTell knows any "complaining" songs (an earlier term for protest songs), to which the singer replies somewhat uncomfortably and evasively that he does not. The Library of Congress paid McTell $10, the equivalent of $154.56 in 2011, for this two-hour session.[4] The material from this 1940 session was issued in 1960 as an LP and later as a CD, under the somewhat misleading title The Complete Library of Congress Recordings, notwithstanding the fact that it was truncated, in that it omitted some of John A. Lomax's interactions with the singer and entirely omitted the contributions of Ruby Terrill Lomax.[note 1]

Ahmet Ertegun visited Atlanta in 1949 in search of blues artists for this new Atlantic Records label and after finding McTell playing on the street, arranged a recording session. Some of the songs were released on 78 rpm discs, but sold poorly. The complete session was released in 1972 as Atlanta Twelve-String. McTell recorded for Regal Records in 1949, but these recordings also met with less commercial success than his previous works. He continued to perform around Atlanta, but his career was cut short by ill health, mostly due to diabetes and alcoholism. In 1956, an Atlanta record store manager, Edward Rhodes, discovered McTell playing in the street for quarters and enticed him with a bottle of corn liquor into his store, where he captured a few final performances on a tape recorder. These recordings were released posthumously by Prestige/Bluesville Records as Last Session.[10] Beginning in 1957, McTell was a preacher at Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Atlanta.[1]

McTell died of a stroke in Milledgeville, Georgia, in 1959. He was buried at Jones Grove Church, near Thomson, Georgia, his birthplace. Author David Fulmer, who in 1992 was working on "Blind Willie's Blues," a documentary about McTell, arranged to have a gravestone erected on his resting place. The name given on his stone is Willie Samuel McTier.[11] He was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Blues Hall of Fame in 1981[12] and the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in 1990.[1]

In his recordings of "Lay Some Flowers on My Grave", "Lord, Send Me an Angel" and "Statesboro Blues", he pronounces his surname MacTell, with the stress on the first syllable.

Influence

[edit]

McTell's most famous song, "Statesboro Blues", was first adapted by Taj Mahal with Jesse Ed Davis on slide guitar, then covered on an LP and frequently performed by the Allman Brothers Band;[13] it also contributes to Canned Heat's "Goin' Up the Country". A short list of some of the artists who have performed the song includes Taj Mahal, David Bromberg, Dave Van Ronk, The Devil Makes Three and Ralph McTell, who changed his name on account of liking the song.[14] Ry Cooder covered McTell's "Married Man's a Fool" on his 1973 album, Paradise and Lunch. Jack White, of the White Stripes, considers McTell an influence; the White Stripes album De Stijl (2000) is dedicated to him and features a cover of his song "Southern Can Is Mine". The White Stripes also covered McTell's "Lord, Send Me an Angel", releasing it as a single in 2000. In 2013, Jack White's Third Man Records teamed up with Document Records to issue The Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order of Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell and the Mississippi Sheiks.

Bob Dylan paid tribute to McTell on at least four occasions. In his 1965 song "Highway 61 Revisited", the second verse begins, "Georgia Sam he had a bloody nose", a reference to one of McTell's many recording names (Note: there is no evidence of use of this moniker on any recordings). Dylan's song "Blind Willie McTell" was recorded in 1983 and released in 1991 on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3. Dylan also recorded covers of McTell's "Broke Down Engine" and "Delia" on his 1993 album, World Gone Wrong;[note 2] Dylan's song "Po' Boy", on the album Love and Theft (2001), contains the lyric "had to go to Florida dodging them Georgia laws", which comes from McTell's "Kill It Kid".[16]

The Bath-based band Kill It Kid is named after the song of the same title.[17]

A billiards bar and concert venue in Statesboro, Georgia, was named Blind Willie's after McTell in the 1990s. The venue is now closed, but remains a fond memory for Georgia Southern University students at the time.[18]

Blind Willie's is a bar in the Virginia-Highlands neighborhood of Atlanta named after McTell that features blues musicians and bands.[19] The Blind Willie McTell Blues Festival is held annually in Thomson, Georgia.[19]

Discography

[edit]Singles

[edit]| Year | A-side | B-side | Label | Cat. # | Moniker | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

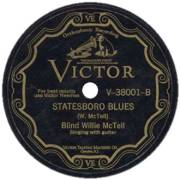

| 1927 | "Stole Rider Blues" | "Mr. McTell Got the Blues" | Victor | 21124 | Blind Willie McTell | |

| "Writing Paper Blues" | "Mamma, Tain't Long Fo' Day" | 21474 | ||||

| 1928 | "Three Women Blues" | "Statesboro Blues" | V38001 | |||

| "Dark Night Blues" | "Loving Talking Blues" | V38032 | ||||

| 1929 | "Atlanta Strut" | "Kind Mama" | Columbia | 14657-D | Blind Sammie | |

| "Travelin' Blues" | "Come on Around to My House Mama" | 14484-D | ||||

| "Drive Away Blues" | "Love Changing Blues" | Victor | V38580 | Blind Willie McTell | ||

| 1930 | "Talking to Myself" | "Razor Ball" | Columbia | 14551-D | Blind Sammie | |

| 1931 | "Southern Can Is Mine" | "Broke Down Engine Blues" | 14632-D | |||

| "Low Rider's Blues" | "Georgia Rag" | OKeh | 8924 | Georgia Bill | ||

| "Stomp Down Rider" | "Scarey Day Blues" | 8936 | ||||

| 1932 | "Mama, Let Me Scoop for You" | "Rollin' Mama Blues" | Victor | 23328 | Hot Shot Willie | with Ruby Glaze |

| "Lonesome Day Blues" | "Searching the Desert for the Blues" | 23353 | ||||

| 1933 | "Savannah Mama" | "B and O Blues No. 2" | Vocalion | 02568 | Blind Willie | |

| "Broke Down Engine" | "Death Cell Blues" | 02577 | ||||

| "Warm It Up to Me" | "Runnin' Me Crazy" | 02595 | ||||

| "It's a Good Little Thing" | "Southern Can Mama" | 02622 | ||||

| "Lord Have Mercy, if You Please" | "Don't You See How This World Made a Change" | 02623 | with "Partner" (Curley Weaver) | |||

| "My Baby's Gone" | "Weary Hearted Blues" | 02668 | ||||

| 1935 | "Bell Street Blues" | "Ticket Agent Blues" | Decca | 7078 | Blind Willie McTell | with Kate McTell |

| "Dying Gambler" | "God Don't Like It" | 7093 | ||||

| "Ain't It Grand to Be a Christian" | "We Got to Meet Death One Day" | 7130 | ||||

| "Your Time to Worry" | "Hillbilly Willie's Blues" | 7117 | ||||

| "Cold Winter Day" | "Lay Some Flowers on My Grave" | 7810 | ||||

| 1950 | "Kill It Kid" | "Broke-Down Engine Blues" | Atlantic | 891 | Barrelhouse Sammy | |

| "River Jordan" | "How About You" | Regal | 3260 | Blind Willie | ||

| "It's My Desire" | "Hide Me in Thy Bosom" | 3272 | ||||

| "Love Changing Blues" | "Talkin' to You Mama" | 3277 | Willie Samuel McTell | with Curley Weaver; attributed to "Pig and Whistle Band" |

- As an accompanist

| Year | Artist | A-side | B-side | Label | Cat. # | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Alfoncy and Bethenea Harris | "Teasing Brown" | "This Is Not the Stove to Brown Your Bread" | Victor | V38594 | |

| 1931 | Ruth Willis | "Experience Blues" | "Painful Blues" | Columbia | 14642-D | |

| "Rough Alley Blues" | "Low Down Blues" | OKeh | 8921 | |||

| "Talkin' to You Wimmin' About the Blues" | "Merciful Blues" | 8932 | ||||

| 1935 | Curley Weaver | "Tricks Ain't Walking No More" | "Early Morning Blues" | Decca | 7077 | |

| "Sometime Mama" | "Two-Faced Woman" | 7906 | McTell plays only on B-side | |||

| "Oh Lawdy Mama" | "Fried Pie Blues" | 7664 | ||||

| 1949 | "My Baby's Gone" | "Ticket Agent" | Sittin' In With | 547 |

Long-plays

[edit]| Year | Title | Label | Cat. # | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Last Session | Bluesville | BV 1040 | recorded in 1956 |

| 1966 | Blind Willie McTell: 1940 |

Melodeon | MLP 7323 | subtitled The Legendary Library of Congress Session; recorded in 1940 |

Selected compilations

[edit]- Blind Willie McTell 1927–1933: The Early Years, Yazoo L-1005 (1968)

- Blind Willie McTell 1949: Trying to Get Home, Biograph BLP-12008 (1969)

- King of the Georgia Blues Singers (1929–1935), Roots RL-324 (1969)

- Atlanta Twelve String, Atlantic SD-7224 (1972)

- Death Cell Blues, Biograph BLP-C-14 (1973)

- Blind Willie McTell: 1927–1935, Yazoo L-1037 (1974)

- Blind Willie McTell: 1927–1949, The Remaining Titles, Wolf WSE 102 (1982)

- Blues in the Dark, MCA 1368 (1983)

- Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, vol. 1, Document DOCD-5006 (1990)

- Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, vol. 2, Document DOCD-5007 (1990)

- Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, vol. 3, Document DOCD-5008 (1990)

- These three albums were issued together as the box set Statesboro Blues, Document DOCD-5677 (1990)

- Complete Library of Congress Recordings in Chronological Order, RST Blues Documents BDCD-6001 (1990)

- Pig 'n Whistle Red, Biograph BCD 126 (1993)

- The Definitive Blind Willie McTell, Legacy C2K-53234 (1994)

- The Classic Years 1927–1940, JSP JSP7711 (2003)

- King of the Georgia Blues, Snapper SBLUECD504X (2007)

Selected compilations with other artists

[edit]- Blind Willie McTell/Memphis Minnie: Love Changin' Blues, Biograph BLP-12035 (1971)

- Atlanta Blues 1933, JEMF 106 (1979)

- Blind Willie McTell and Curley Weaver: The Post-War Years, RST Blues Documents BDCD 6014 (1990)

- Classic Blues Artwork from the 1920s, vol. 5, Blues Images – BIM-105 (2007)

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ McTell's biographer Michael Gray attributes these omissions to the folklore archivist Rae Korson, who was evidently hostile to his New Deal folklore predecessors at the library: "The widely sold version of the McTell-Lomax sessions deletes conversations and information, removes Ruby Lomax from the room almost entirely—making John Lomax seem to monopolize things and keep her silent, which he doesn't at all—and robs Lomax of several touches of warmth and humanity, including questions asked by Ruby Terrill and John Lomax."[9]

- ^ In the liner notes for that album, Dylan wrote, "'Broke Down Engine' is a Blind Willie McTell masterpiece ... it's about Ambiguity, the fortunes of the privileged elite, flood control—watching the red dawn not bothering to dress [sic]."[15]

3.^In 1996, novelist and former music journalist David Fulmer released “Blind Willie’s Blues,” a 53-minute documentary

about McTell’s life, times, and music. The film was remastered for a new release in December of 2023 and is currently

streaming on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8iPBtbcJsM&t=48s

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Jacobs, Hal. "Blind Willie McTell". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. November 3, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c Conner, Patrick. "Blind Willie McTell Archived November 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". East Coast Piedmont Blues. University of North Carolina. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. p. 270. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- ^ a b Green, Justin. Musical Legends. ISBN 0-86719-587-8.

- ^ Giles Oakley (1997). The Devil's Music. Da Capo Press. pp. 125/7. ISBN 978-0-306-80743-5.

- ^ "Pig'n Whistle | Pig'n Whistle Georgia History". Pignwhistle.net. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Russell, Tony (1997). The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray. Dubai: Carlton Books. p. 13. ISBN 1-85868-255-X.

- ^ "Audio Recording: Amazing Grace". loc.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ Gray 2009, p. 273.

- ^ "Blind Willie McTell". bluesnet. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2006.

- ^ "Willie 'Blind Willie' McTell (1901–1959)". Findagrave.com. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "1981 Hall of Fame Inductees". Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Robert Palmer (1982). Deep Blues. Penguin Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- ^ Hockenhull, Chris (1997). Streets of London: The Official Biography of Ralph McTell. Northdown. p. 40. ISBN 1-900711-02-8.

- ^ Dylan, Bob (1993). World Gone Wrong (liner notes). Special Rider Music. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "Kill It Kid", Last Session, Bluesville BV 1040, released 1962.

- ^ "kill it kid interview sxsw 2010". Spinner.com. March 12, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ "I partied at Blind Willies (Statesboro, Ga.)". www.facebook.com. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "Blind Willie's – Atlanta's Finest Blues Bar". Blindwillieblues.com. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

Works cited

[edit]- Gray, Michael (2009). Hand Me My Travelin' Shoes. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-337-7. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

General references

[edit]- Bastin, Bruce. Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986, 1995. ISBN 0-252-06521-2, ISBN 978-0-252-06521-7.

- Charters, Samuel, ed. Sweet as the Showers of Rain. Oak Publications, 1977, pp, 120–131.

External links

[edit]- New Georgia Encyclopedia – Blind Willie McTell article

- Illustrated Blind Willie McTell discography

- Blind Willie McTell at Find a Grave

- "Statesboro Blues" MP3 file on the Internet Archive

- David Fulmer, producer "Blind Willie's Blues" Documentary film, 1996

- "The Dying Crapshooter's Blues" Novel by David Fulmer featuring McTell as a character

- John May interviews biographer Archived October 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Michael Gray

- Review of Hand Me My Travelin' Shoes: In Search of Blind Willie McTell by Michael Gray

- 1898 births

- 1959 deaths

- African-American male singer-songwriters

- American male singer-songwriters

- American acoustic guitarists

- American blues guitarists

- American blues harmonica players

- American blues singer-songwriters

- American male guitarists

- American street performers

- Blind musicians

- Blind singers

- Bluebird Records artists

- Columbia Records artists

- Country blues musicians

- East Coast blues musicians

- People from Thomson, Georgia

- Piedmont blues musicians

- Ragtime composers

- Songster musicians

- 20th-century American guitarists

- Guitarists from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Prestige Records artists

- Transatlantic Records artists

- Third Man Records artists

- African-American guitarists

- 20th-century African-American male singers

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- Singer-songwriters from Georgia (U.S. state)

- American blind people

- American musicians with disabilities